Cu referire la relațiile cetățenilor români cu unele posturi de radio capitaliste. In Securitatea, 41 (1978): 38-49. Articol

Cu referire la relațiile cetățenilor români cu unele posturi de radio capitaliste. In Securitatea, 41 (1978): 38-49. Articol

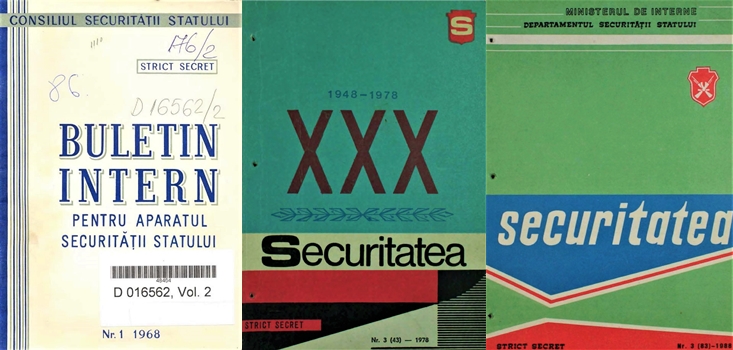

Securitatea was a quarterly aimed at improving the training of Securitate operative personnel. Its articles were written by Securitate officers for Securitate officers and thus they touched upon practical problems faced during their specific mission of preventing and neutralising any actions that potentially threatened the communist regime. Among the many dangers that were outlined in the pages of the quarterly as undermining “state security” were foreign radio stations, and especially Radio Free Europe (RFE). The article chosen as a featured item of the collection presents under the title “Cu referire la relațiile cetățenilor români cu unele posturi de radio capitaliste” (About the relations of Romanian citizens with some capitalist radio stations) the perspective of the Securitate upon the activity of RFE and evaluates its contribution in providing an alternative source of information for Romanians. In the absence of underground publications, RFE represented the main source of alternative information in communist Romania. Thus, the Securitate regarded RFE and contacts between Romanian citizens and employees of the Romanian desk of this radio station as dangerous to the communist regime. Accordingly, the entire article focuses on revealing how RFE allegedly acts in order to undermine “state security.” Starting from the premise that RFE is the locus “of espionage, ideological diversion, and hostile propaganda,” the anonymous author traces the connection between this radio station and the American espionage machine, namely the CIA. The Central Intelligence Agency was credited with financing RFE and setting its agenda even after the American Congress officially took responsibility for financially supporting its functioning. The control of the CIA over RFE was underlined once again when discussing its organisation. The two management structures in the United States and Europe were allegedly infiltrated by CIA agents who engaged the radio station in their “ungentlemanly” war against communist countries and used it to collect information about them. As a result, the CIA used the microphone of RFE to proffer slanders and shamefully distort the realities of the communist countries, according to the Securitate’s interpretation of the broadcasting of news and other political programmes by this radio station. Even worse from the point of view of the Securitate was that people travelling abroad were an easy prey for “agents” working at the Romanian desk of RFE. After underlining the connection between its director, deputy director, and programme producers with the CIA, the article describes how they allegedly succeeded in manipulating Romanian tourists in order to collect valuable information about the country, its leadership, and the impact of its social and economic policies on the mood of the population. In other cases, they even managed to trick their “victims” and persuade them to emigrate. The narrative of blaming RFE for these “unpatriotic” deeds was an ideologically convenient explanation for the fact that the great majority of Romanians listened to and trusted RFE, in spite of the fact that this might have caused problems. At the same time, such a narrative was meant to highlight the vital role played by the Securitate as a guardian of the communist regime in Romania.

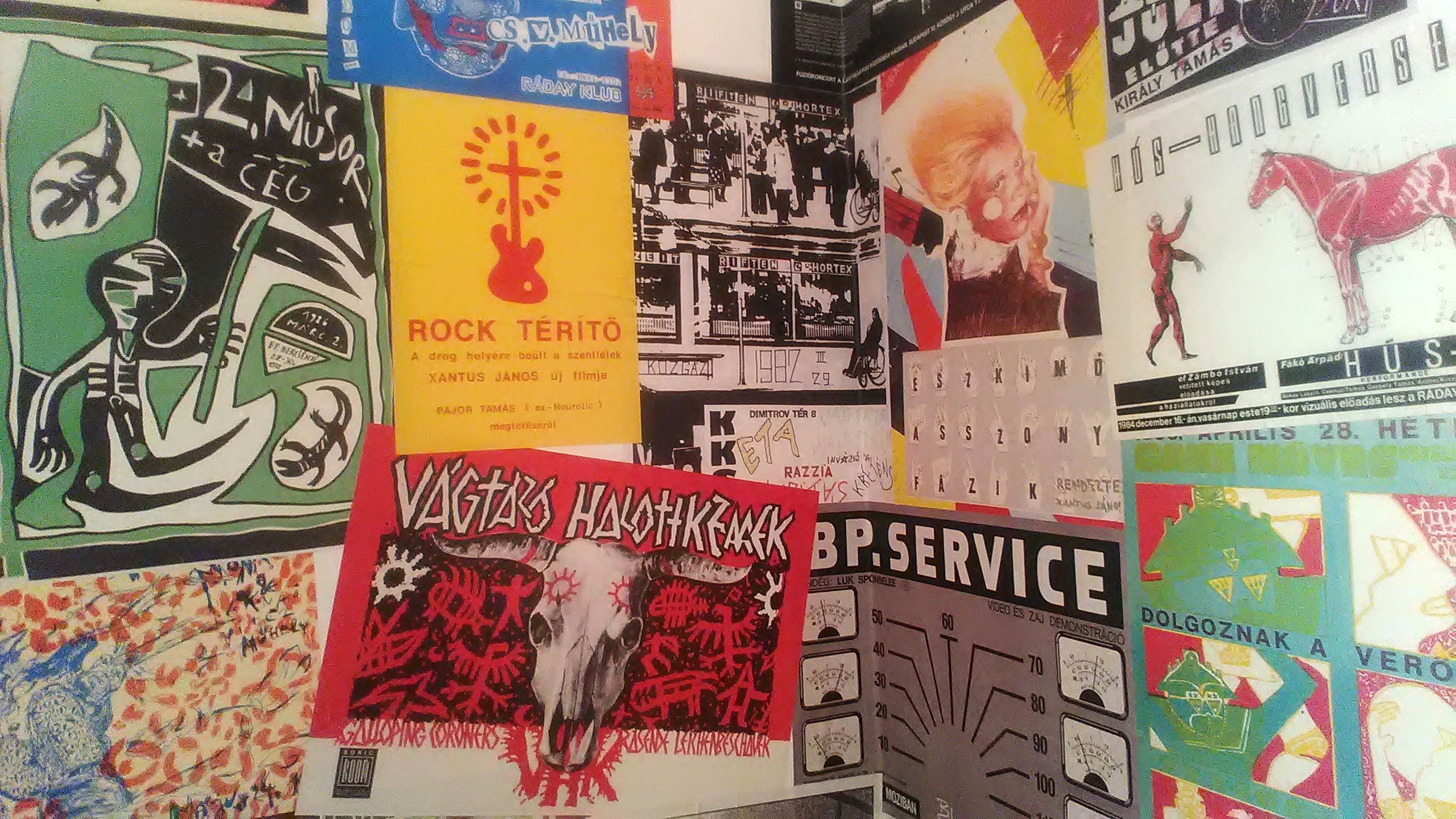

The Velid Đekić collection covers beginning of rock and disco culture not only in Rijeka but also in the former Yugoslavia. While working on the books 91 decibels (2009) and Red! River! Rock! (2013), Đekić collected materials on many of Rijeka's bands that have existed from the late 1950s until the early 1980s, and on the places where young people gathered. That is why this collection testifies to the unique history of rock 'n' roll behind the Iron Curtain.

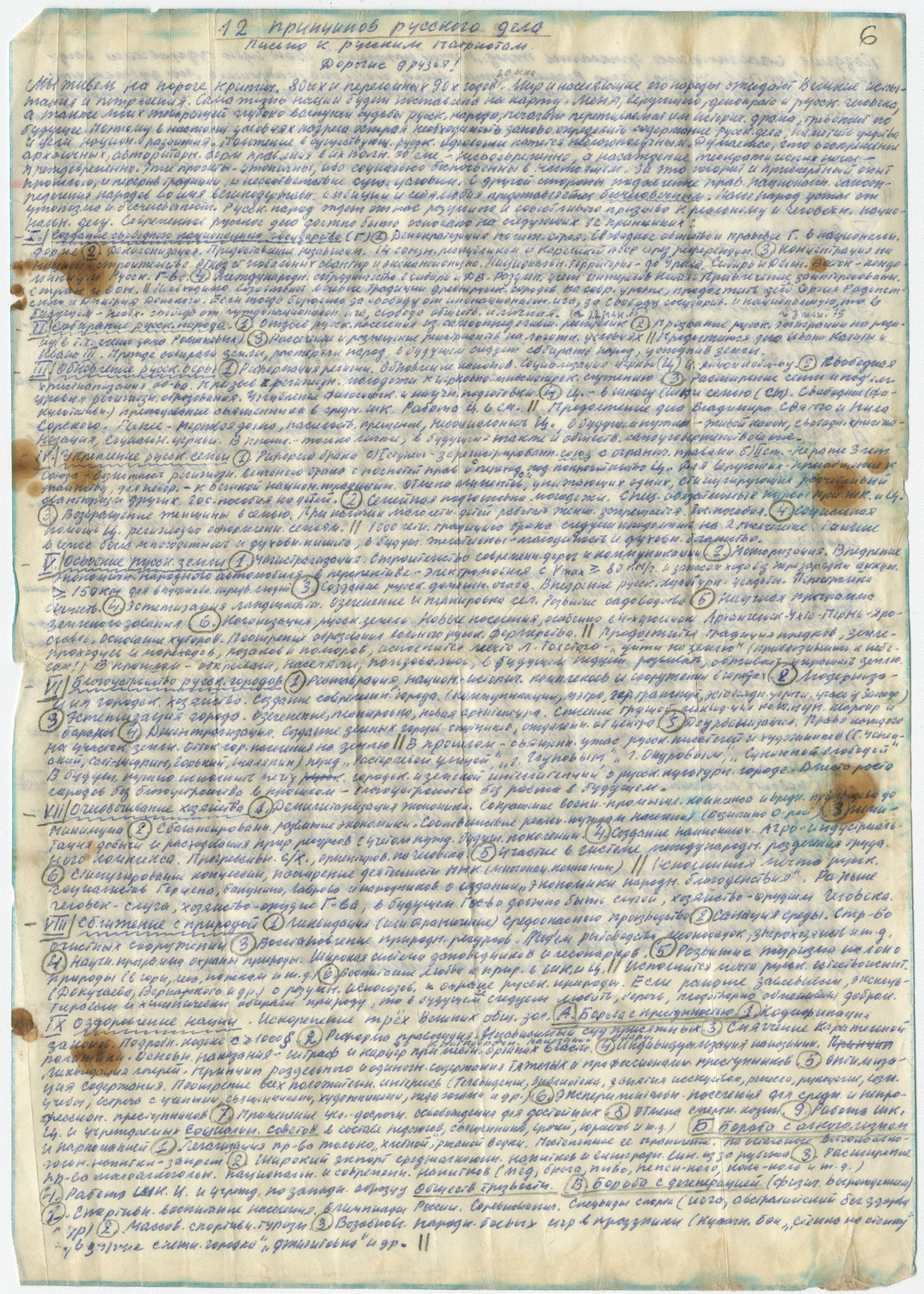

This letter is an important document for the history of the post-war Romanian exile community because it is a proof of the attempt of a Romanian dissident to establish a connection with the emigration. The purpose was to gain the support of Romanians abroad. If their situation was publicised in the West, then there were chances that once returned to their country they would not suffer the reprisals of the communist regime. Also, such actions were meant to trigger the support of international public opinion in criticising Nicolae Ceausescu's dictatorship. One such example was the action of the Romanian writer and journalist Victor Frunză during a tour in France in 1978. In Paris, he wrote a letter to Eugène Ionesco (Eugen Ionescu), a French-language writer originally from Romania, a representative of the theatre of the absurd and a member of the French Academy. In this document, sent on 8 September 1978, Victor Frunză informed Eugène Ionesco that, in France, he criticised openly the situation in communist Romania, especially the personal power and personality cult of Nicolae Ceaușescu. Starting from the idea that he was not the first Romanian and hopefully not the last to do so, Frunză told Ionesco that his approach was deliberately chosen, in full awareness of the possible consequences for him: "When I did this, I knew what I could expect, but I have defeated my fear (...). The sense of the justice of my criticisms gives me the strength to resist. There is no fear of the reprisals that will come anyway, but in the face of the fears of others who can in my mind support me, and in fact will leave me. Immense is the fear of staying alone, as in a desert." In conclusion, Victor Frunză asked Eugène Ionesco to publicly support his action of criticising the dictatorship and personality cult of Nicolae Ceaușescu.

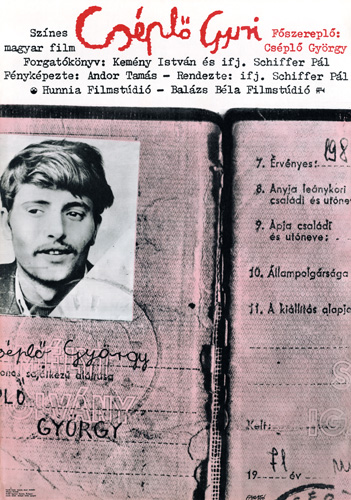

Antoine and Désiré can be considered a concept album. Released in 1978, it was Cseh’s second album. The protagonists mentioned in the title appear on the sleeve, thanks to the photo series by János Vető. They are impersonated by two people who were well known in underground circles of the time: Dixi, the poet and Zuzu, the painter. Two (fictional) biographies are also included.

As the author of the lyrics, Géza Bereményi, notes in his account, Dixi and Zuzu only lent their faces to the cover photos. The biographies reveal two typical life stories from the 1970s, one person who earns reasonably well and another who is less successful in career, nonetheless they remain friends, in spite of their different fates. According to the authorial account, they were inspired by archetype of the white and the red clown, so all the songs on the album can be considered parts of a series of clown pranks. The red clown is Désiré: the saunterer, an awkward kid; the white is Antoine: the successful adult.

In some songs, the voice of Desiré can be heard, in others a narrator tells the story, giving the singer a chance to identify with the character, but also to exit the role. The play with the alternation of identification and distancing is a returning element in their songs. The lyrics balance between the possibilities of speaking out and concealment, and partly expressed sentences and unnamed circumstances are frequent, and this accurately portrays the lives and prospectives of the protagonists. The songs are strongly atmospheric beyond the stories, and they give a precise account on the era through the sentiments they evoke.

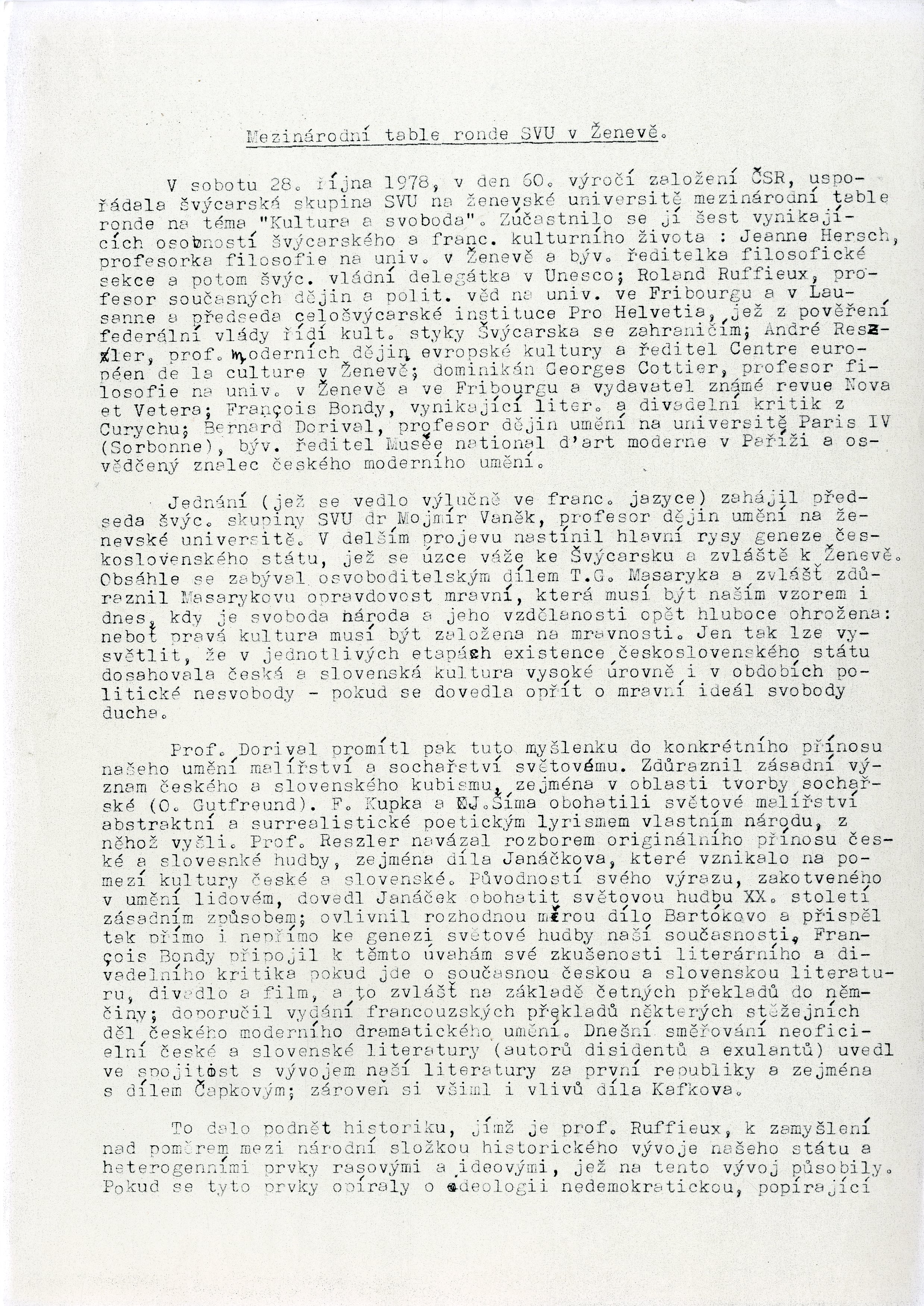

Minutes from the International Table Ronde SVU in Geneva were kept by Mojmir Vanek, the main organizer of the Symposium, as well as the Chairman of the Swiss Group of the Society for Science and Art (SVU) in the aftermath of the Symposium.

On two pages of machine-written text Vaněk describes the course of the symposium and who participated in it, as well as the course of discussion. The Symposium on “Culture and Freedom” was held on 28 October 1978 to mark the 60th anniversary of the founding of Czechoslovakia on behalf of the Society for Science and Arts. The so-called table ronde was held in French and was attended by six prominent people from Swiss and French cultural life: President Pro Helvetia, R. Ruffieux (Lausanne and Friborg), B. Dorival (Paris-Sorbonne), Jeanne Hersch (Geneva), G. Gottier (Geneva) and literary critic Francois Bondy (Zurich). This event was exceptionally well received in the Swiss press as well as in Czechoslovakia. Mojmir Vanek presided over this symposium.

This symposium, and especially Mojmir Vaněk´s speech at the beginning of the negotiations, was likely the reason why his Czechoslovak citizenship was revoked only a month after the symposium was held. This entry is the unique testimony of Mojmir Vanek about this symposium and was likely used as a record for the Society for Science and Art. Vanek himself regarded this event as an international manifestation, which at its level and its international focus was still the most significant enterprise of the Swiss group of the SVU.

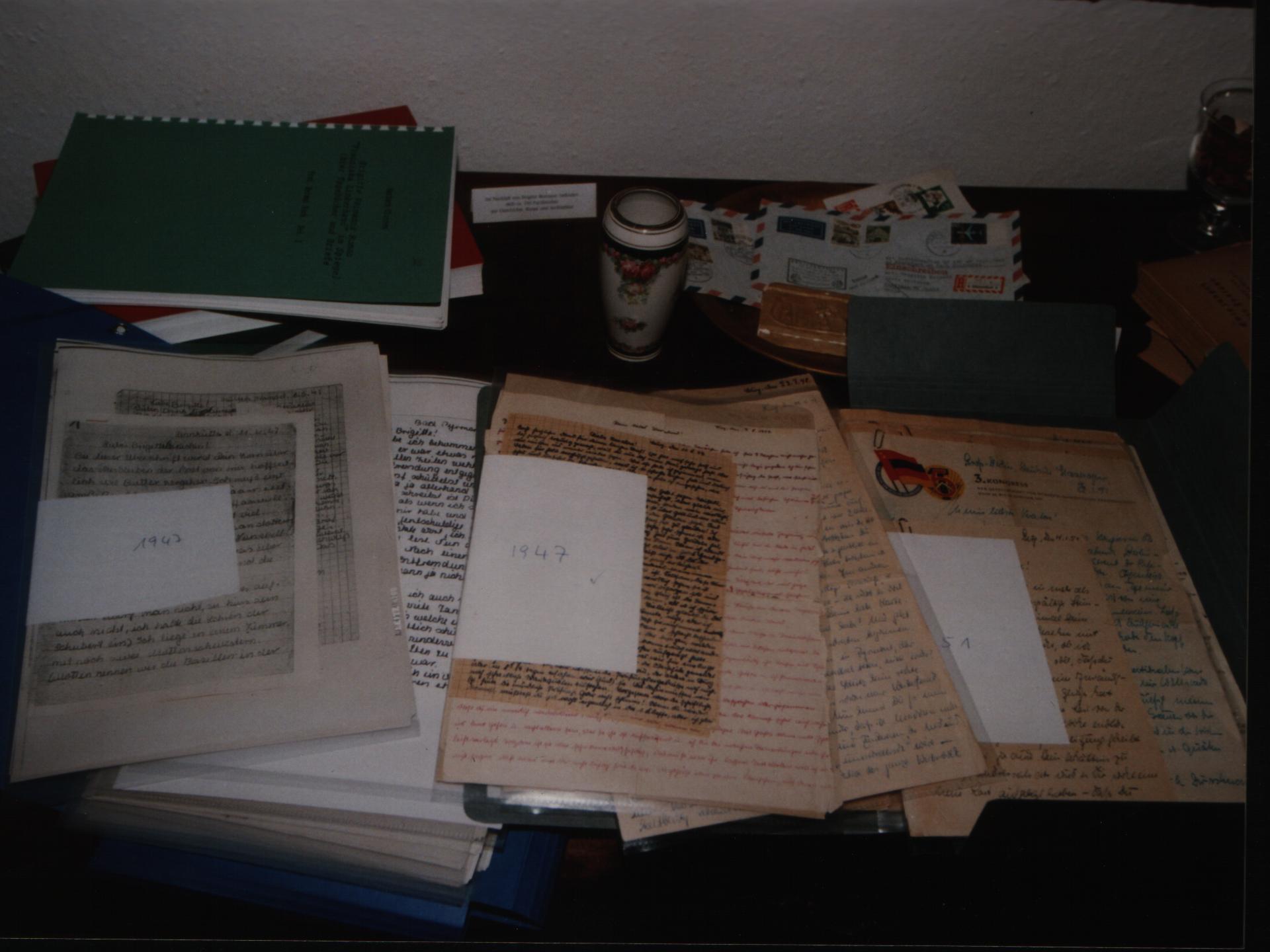

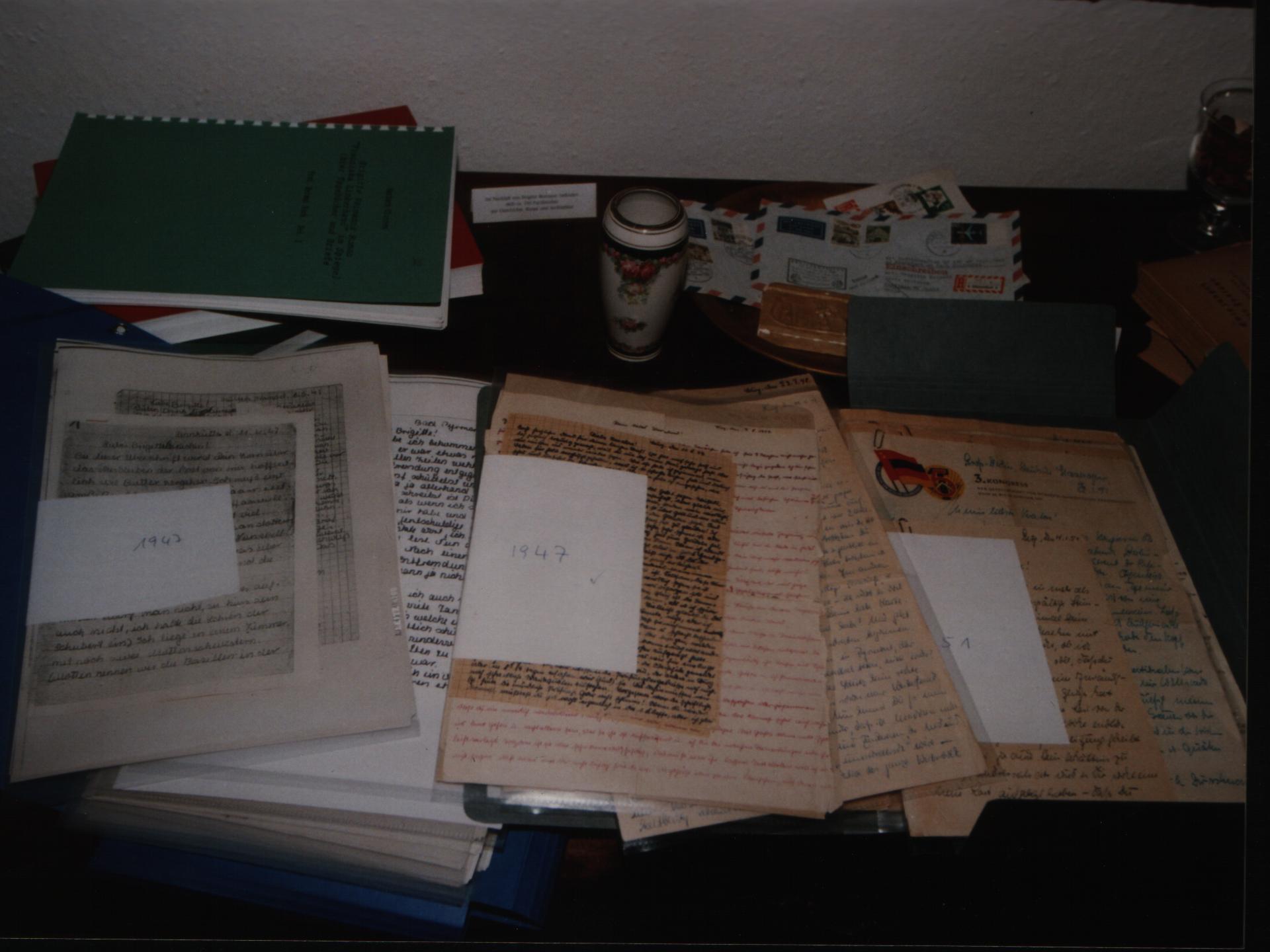

A folder contains Soldatov’s original letters and notes written on rolls of paper. His letters and notes were smuggled one by one out of the prison camp by his wife Ludmilla when she visited him. These writings included several philosophical and religious contemplations, which were later published in Soldatov’s collected works.

Mojmír Vaněk organized a symposium on the topic "Culture and Freedom" on the occasion of the 60th anniversary of the founding of Czechoslovakia and on behalf of the Society for Science and the Art (SVU) on 28 October 1978. The so-called table ronde was held in French and was attended by six prominent people from Swiss and French cultural life: President Pro Helvetia, R. Ruffieux (Lausanne and Friborg), B. Dorival (Paris-Sorbonne), Jeanne Hersch (Geneva), G. Gottier (Geneva) and literary critic Francois Bondy (Zurich). This event was exceptionally well received in the Swiss press as well as in Czechoslovakia. Mojmír Vaněk presided over this symposium.

The event started by dr. Mojmír Vaněk as chairman of the SWU Swiss Group, where he outlined the main features of the genesis of the Czechoslovak state, which is closely linked to Switzerland. He talked extensively about Tomáš Garrigue Masaryk's liberation work and stressed Masaryk's morality, which he felt was a model at a time when the freedom of the nation and its education were once again profoundly threatened, and when true culture must be based on morality. The audience of this symposium filled one of the biggest lecturers of the new university building in Geneva.

Likely in connection with this event, in November of that year, the Ministry of Interior of the Czechoslovak Republic had revoked Vaněk’s citizenship. His wife, Olga Vaňková, who was also a member of the Society for Science and the Arts, had her citizenship revoked as well.

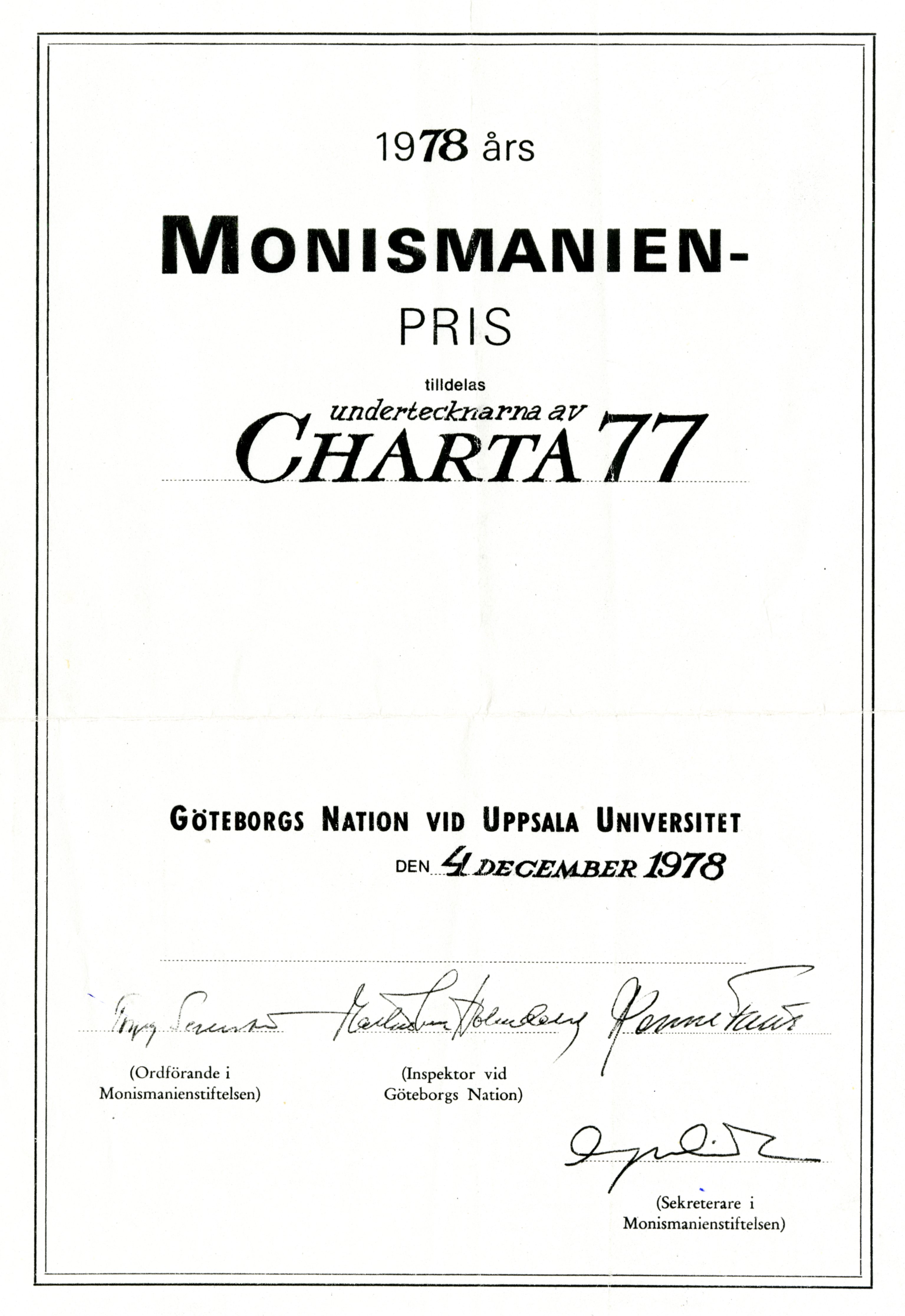

The Diploma of the Monismanien Cultural Prize, inspired the foundation of the Charter 77 in Stockholm. The foundation was founded on the initiative of writer Vaclav Havel after the Charta 77 civic movement was awarded the Monismanien Prize for "its struggle to promote the fundamental human right to freedom of expression." On behalf of Charter 77, he took the prize at the University of Uppsala on December 4, 1978 from the hands of its rector, Professor Frantisek Janouch, who read the letter of the spokesmen of Charter 77 Václav Havel and Ladislav Hejdanek. The prize, which was subsidised with a sum of 15,000 Swedish crowns, was used to set up a fund to support the Czechoslovak citizens, persecuted for their participation in Charter 77, and families of Czechoslovakia. On the occasion of the Monismanien Prize, a call was made to the Scandinavian and international public asking for support for the persecuted opponents of the communist regime in Czechoslovakia. After a successful response, it managed to get more money from private donors and organisations. Thus, this supportive activity was formalised and the Charter 77 Foundation was founded, which until 1989 supported the Czechoslovak opposition. The foundation was led by Professor Frantisek Janouch throughout his life. The diploma of the Monismanien cultural monument in Sweden is only a copy in the collection, the original was probably sent by the Charter 77 spokesperson to Prague.

The personal collection of Czech poet, journalist, writer and the Nobel Prize laureate Jaroslav Seifert (1901–1986) contains a unique correspondence, manuscripts, prints and clippings documenting the life of the important author, who was a critic of the communist regime from 1950 and a silenced poet and a representative of Czechoslovak independent literature after August 1968.

He estimates that, he was called before the Cultural Committee of the League of Communist Youth of Vojvodina at least twice per year, which he considered to be tyrannical. “These people lack a fundamental understanding of what I’m doing. There are exceptional analytical texts that address certain phenomena: death, literature, irony, postmodernism…those various qualities within modern society and culture that expose a new reality and that introduce new questions to our culture. So what do they do? They file a forty page report. Should I kill myself over it? I sit there instead, forced to listen to this nonsense, and worry that I’ll be replaced. And they all continue on, with business-minded faces, going through papers and discussing them as if it were the last judgement of the Provincial Youth Alliance. (…) The people of the party who oversee everything came from the PC (Provincial Commune of the League of Communists of Vojvodina, cf. Aut). I was a young man then. And the Youth Union was assigned to eradicate not just me, but the entire editorial board.”Among the various forms of persecution, Zivlak also noted that every day for two months, a police officer required him to identify himself before entering the editorial office. Jovan Zivlak is forthright about psycho-somatic problems that he developed because of these pressures. He speculates that the only reason he remained editor-in-chief of Polja for eight years was because Novi Sad lacked the media to carry out a personal attack on him.

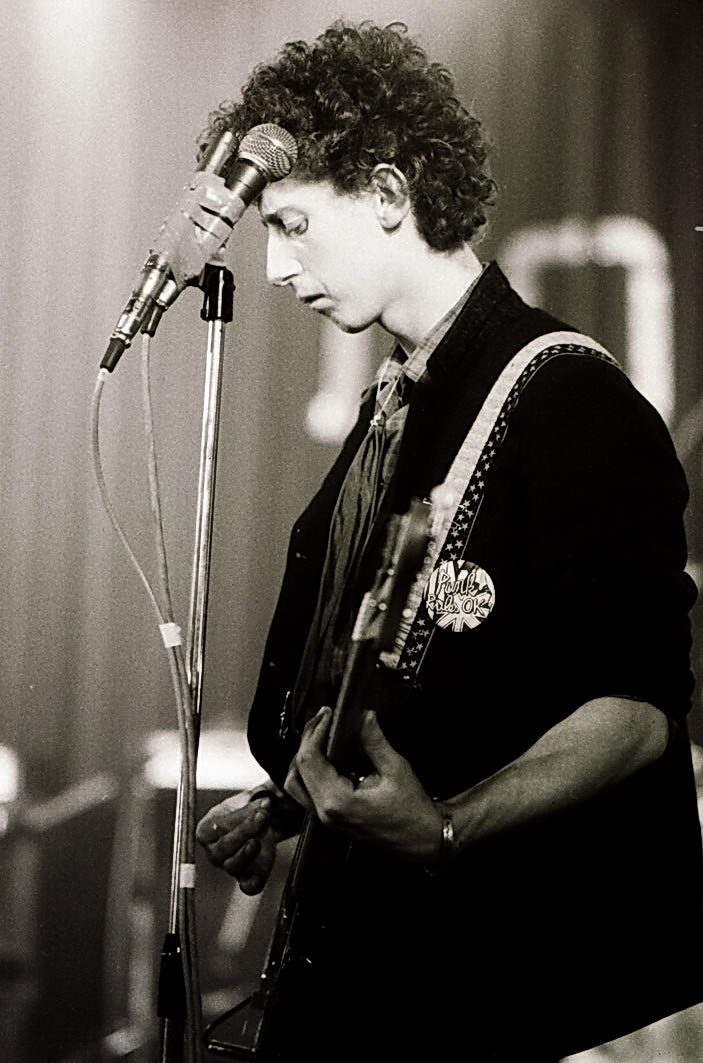

The photo shows the first line-up of the band Azra in Gospić in October 1978. The concert was part of the first tour of Azra organized by Polet. The first line-up consisted of Branimir Johnny Štulić, Jura Stublić, Marino Pelajić, Branko Hromatko and Mladen Max Juričić. In 1979, Jura Stublić, Marino Pelajić and Mladen Max Juričić left Azra and founded the group Film. With Azra soon reformed by Johnny Štulić, the group Film became one of the leaders of the new wave scene not only in Zagreb but also throughout Yugoslavia.

After the strike in Gdansk in August and September 1980 and the establishment of the Solidarity trade union, which meant the beginning of the fall of communism in Poland, Štulić wrote the song "Poland in my heart." It expresses explicit support to events in Poland, and mentions Wojtyla, i.e. Pope John Paul II. Among the young people in Yugoslavia, this song was perceived as a call to freedom from communism and cultural disagreement with the older generation who were in the Party.

After one concert and eight studio albums, Azra broke up in 1990. After several changes in the original line-up, group Film continued to perform and still plays today under the name Jura Stublić & Film.

Articol din FAZ despre o Scrisoare a lui Victor Frunză către Nicolae Ceaușescu, în germană, august 1978

Articol din FAZ despre o Scrisoare a lui Victor Frunză către Nicolae Ceaușescu, în germană, august 1978

This letter is an important document for the history of dissidence in Romania, being a proof of the open opposition of a Romanian living in the country to the dictatorship of Nicolae Ceaușescu. In this case the writer was Victor Frunză, a Romanian writer and journalist, who in 1978 went as tourist to Paris. On this occasion, he contacted a representative of the Reuters Agency, to whom he handed a letter addressed to Nicolae Ceaușescu. He wrote the text of the letter in Romania and memorised its content in order not to carry it and be discovered at customs control. So he rewrote it from memory after he arrived in France. The material in question was published by Frankfurter Algemeine Zeitung and broadcast by Radio Free Europe. Also, a copy of the letter was sent by Victor Frunză, by post, to Nicolae Ceaușescu. Essentially, his letter was a criticism of Ceausescu's dictatorship: "I want to manifest deep disagreement with the revival of the cult of personality, today is an improved version, decorated with the national flag." Frunză's conclusion was that "the type of socialist democracy in Romania is nothing more than a parody of discussions through speeches, even if these are not written by those who speak them." The document is in the IICCMER archive and is an original copy of the German letter published in 1978 in Frankfurter Algemeine Zeitung. The letter was subsequently published by Victor Frunză in Romanian, at the publishing house he founded after the emigration, in the pages of the book For Human Rights in Romania (1982). The second edition of this volume appeared in 1990, in Bucharest, under the aegis of Victor Frunză Publishing House.

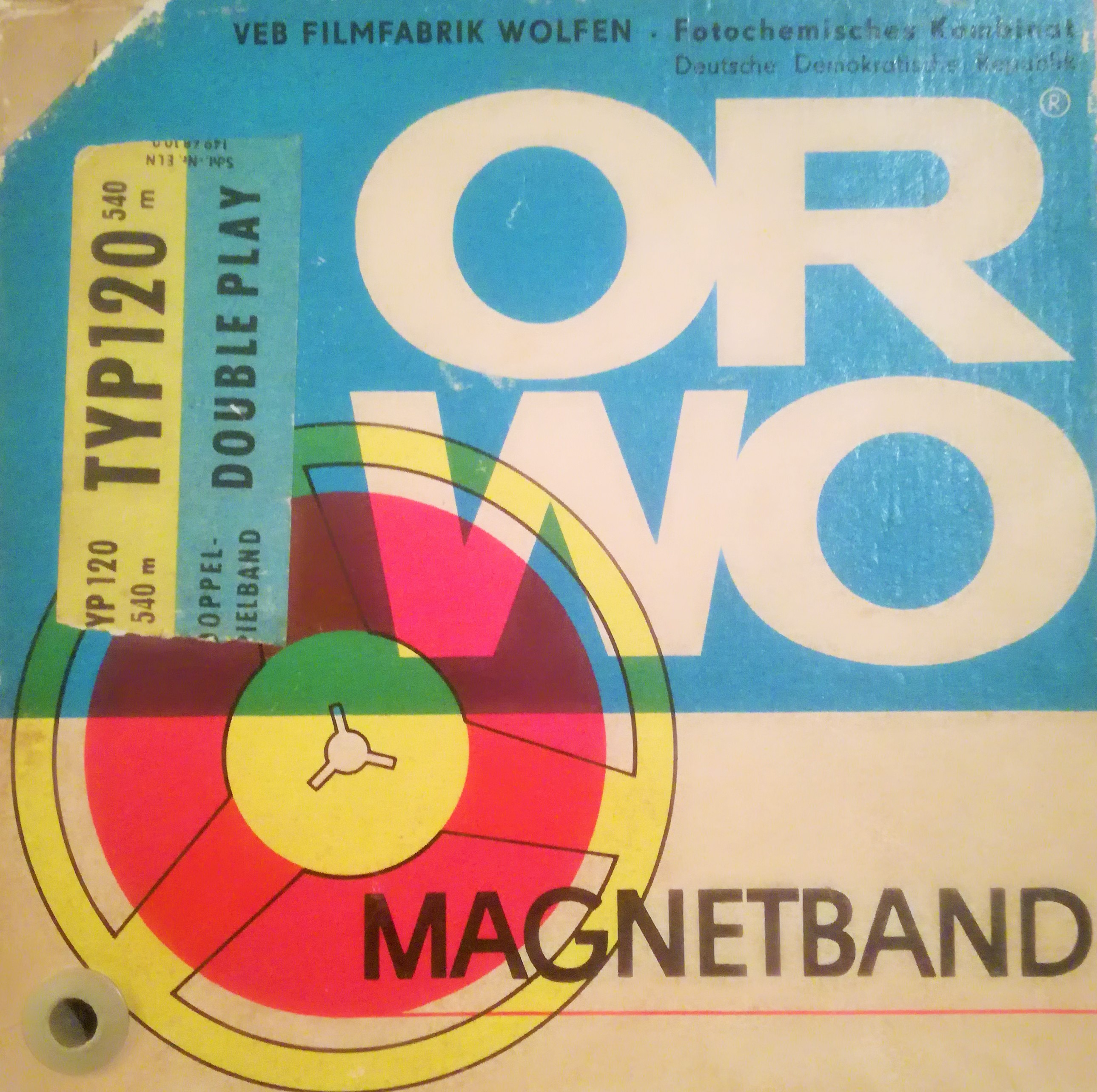

According to very early notes and recordings, István Darkó began work on Macskarádió (Cat radio) while at high school, in the early 1970s, using stories from his home-made paper Bendzin and his comic-experiment Utazás a világ körül (Journey around the world) together with other writings, and it continued to grow until the end of his university years, in 1978. Darkó's first tape recorder was the famous Hungarian Mambó, acquired from his parents; later he used a SANYO. He was very inventive, because he knew the technical possibilities of the poor-quality tape recorders. He worked not with the switch cabinet but with his hand, manually touching the tape to the recording head during recording. He did everything with one tape recorder and one microphone.

The audio recordings of Cat Radio are preserved on East-German-made tape with the series mark ORWO TYP 120/360 m Double Play, 5/482. The box is labelled “A MACSKARÁDIÓ különműsora” (Special programme of CAT RADIO). Macskarádió I. (Cat radio I.), the full story itself, is on the first track, and Macskarádió II. (Cat radio II.), which is looser in its structure, composed as an evening music programme, is on the second. On a second tape Darkó stored the various sounds needed for the radio play, for example the clacks of train wheels and animal noises.

Cat Radio is not only a studio, but a spiritual place, where things come together, meet, or break up, an occult place, where the arrangement and matching of the stories takes place. All the characters speak through the voice of Darkó, with the bon ton (mannered, polite) Hungarian movie voice of the 1940s. But these are experienced voices; the performer only ever spoke in the sanctuary of Cat Radio when sufficiently aroused. He made the audio recording in stages. The elaboration of each detail, each sequence is mental. According to Péter Egyed, the fact that Darkó created it over such a long period made it an endlessly complicated story. There are at least three levels, though this is hard to realise after hearing it once or even two or three times. Because of its metaphysics and because of its complicatedness it is obvious that the radio play was not made for a broad public audience. The constant element in the events is persecution. The characters are divided mainly in three groups. As a matter of fact there is a battle of intentions going on, in which the secret service type of deception is crucial. It is a matter of make-believe, gullibility; who is capable of reconstructing the true reality in virtual sound fields?

In Cluj and in Târgu Mureș the world, or rather worlds, constructed by István Darkó became known. When wanted to be in his element among his acquaintances and friends, he got out Cat Radio and let them listen to it. They listened to it, word leaked out, and the notoriety of Cat Radio exceeded theoretically and also practically the narrower circle of his friends. There was a mystical quality about it. It did not spread samizdat-like, because there was only one original tape, of which a copy was never made. But the fact that this tape was listened to by 10–20–50–100 people and so on made it a semi-public production. What runs on the tape is a continuous analysis of being. In Darkó's world there is a bit of the Orwellian, the hereafter, the world of passing, of things that have not come yet, that cannot be experienced by living people. In his view of life there is also an extraordinary closeness of death. Let's be careful, because we live in a world in which the other one is contained too, even if we don't want to acknowledge it!

When interpreting Cat Radio, Péter Egyed could not ignore the space and time parameters of its appearance. He believed that the material of Cat Radio could not exist independent of what István Darkó had experienced. Why did he not write something else? According to Egyed the Securitate, the state Party and other official agencies were not well-intentioned administrators of humanity, but people following orders and those orders were not about serving the good of civil society. They – contemporaries – were actually playing something according to the script of the multilaterally developed socialist society. It had to be played that things were all right, but everyone knew that it was actually about something else than what they were playing. In the script there is not real life, but Nothing – but where was real life then? Egyed thought that real life was located in what they experienced in intimacy, and what came up in intimacy, real friendships, love relations etc. Society had a life that supported this, as opposed to that which wanted to destroy it. In the army their officers told them that they, the intellectuals, were not needed for the country, either as intellectuals nor as soldiers. They were the "negligible quantity" and they were made to understand that they did not count from the point of view of the socialist future.

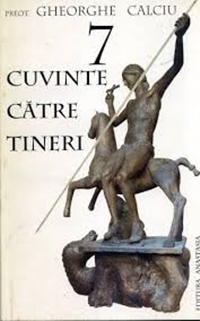

This eighty-eight-page manuscript contains the texts of eight sermons and seems to have been prepared to be sent abroad for publication. The author was a priest and professor at the Theological Institute in Bucharest, and was imprisoned between 1948 and 1964. While in the notorious prison of Pitești, he was forced to take part in the infamous re-education experiment in that prison, which turned a part of the prisoners into the torturers of the others. Tormented by such a terrible sin, Calciu-Dumitreasa tried, according to his own confession, to write about this prison experience in order to come to terms with it. However, he changed his priorities when, in the aftermath of the earthquake of 1977, the demolition of churches in Bucharest began while the hierarchy of the Romanian Orthodox Church kept quiet. It was then that Calciu-Dumitreasa conceived this series of non-conformist sermons, in which he argued against atheist education and reminded his students of fundamental Christian values, of their mission as priests who must build, and not destroy, churches in order to take care of their parish communities. Seven of the sermons were delivered by the author in the Radu Vodă Church in Bucharest between 8 March and 19 April 1978. Particularly important is the sermon of 15 March 1978, in which Calciu-Dumitreasa explicitly condemned the demolition of the Enei Church, the first church demolished in Bucharest. The sixth sermon, of 12 April 1978, was no longer delivered in the church but in front of it, for the authorities had closed the church and locked the students in their dormitories in order to impede them from attending what had turned in the meantime into an increasingly popular event. The eighth sermon was supposed to open a new cycle entitled “Christianity and Culture” on 17 May 1978, but it was never delivered due to the author’s removal from his teaching position. Continuously harassed by the secret police, in 1979 Calciu-Dumitreasa endorsed the establishment of the Free Trade Union of the Working People of Romania, which caused his arrest and imprisonment for another five years. He was released only in 1985, after intense international lobbying, especially by the United States administration, which threatened the Romanian communist regime with the withdrawal of Most Favoured Nation status. A year later, he went into exile in the United States, where he remained until his death. This manuscript was probably confiscated on the occasion of his arrest in 1979. This version of the sermons differs slightly from the post-communist published volume because it mentions the persons who were responsible for the interruption of his cycle of sermons in 1978.

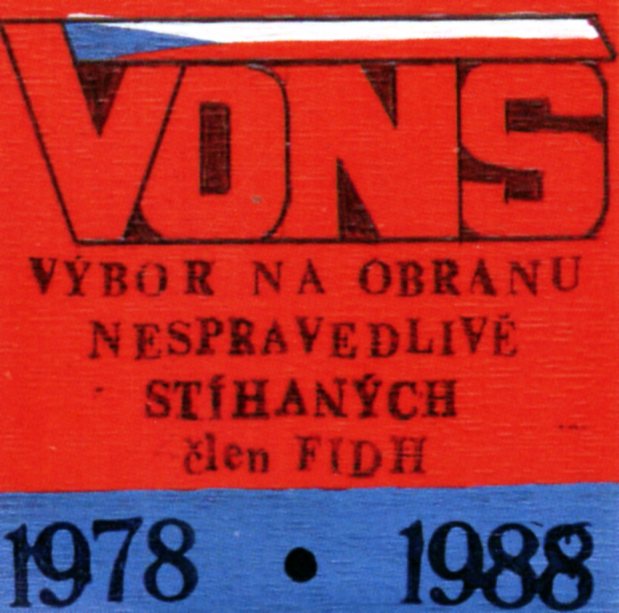

Zakládající prohlášení Výboru na obranu nespravedlivě stíhaných (VONS) z 27. dubna 1978, které podepsalo sedmnáct signatářů Charty 77, kteří zde zveřejnili své adresy, aby se na ně lidé mohli obracet. Cílem VONS bylo sledovat případy osob, které byly trestně stíhány či vězněny za projevy svého přesvědčení nebo které se staly oběťmi policejní a justiční svévole. VONS prostřednictvím číslovaných Sdělení s těmito případy seznamoval domácí i mezinárodní veřejnost a žádal československé úřady o nápravu. Nespravedlivě pronásledovaným a vězněným pomáhal se zajišťováním právního zastoupení a zprostředkováním finanční pomoci.

Impulzem ke vzniku VONS byly mj. události spojené s plesem železničářů v lednu 1978, kterého se chtěli zúčastnit signatáři Charty 77. Státní bezpečnost však tři z nich zadržela. Na jejich podporu vznikl Výbor na obranu Václava Havla, Pavla Landovského a Jaroslava Kukala, který shromáždil podklady pro jejich obhajobu a o celém případu informoval domácí i zahraniční veřejnost. Obvinění byli po šesti týdnech propuštěni a trestní stíhání bylo zastaveno. To bylo velkou vzpruhou pro členy výboru i další disidenty, a tak byl v květnu 1978 založen VONS.

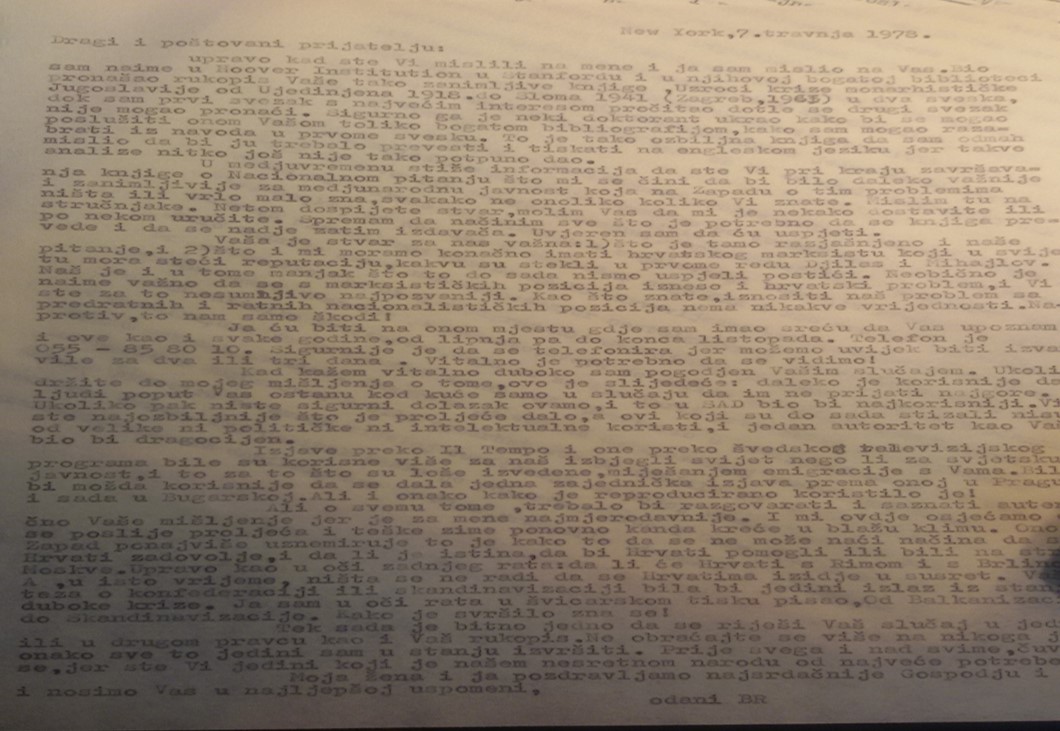

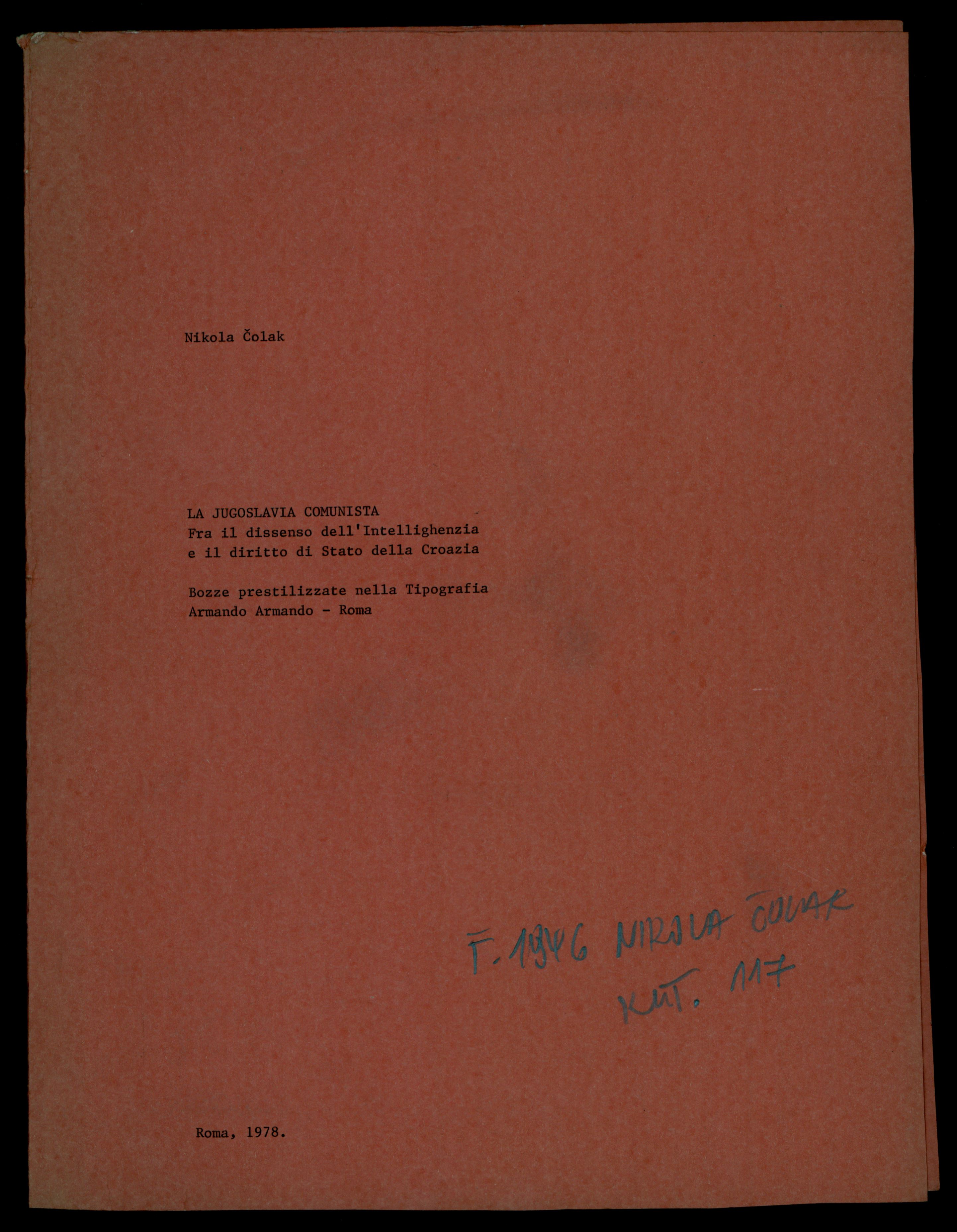

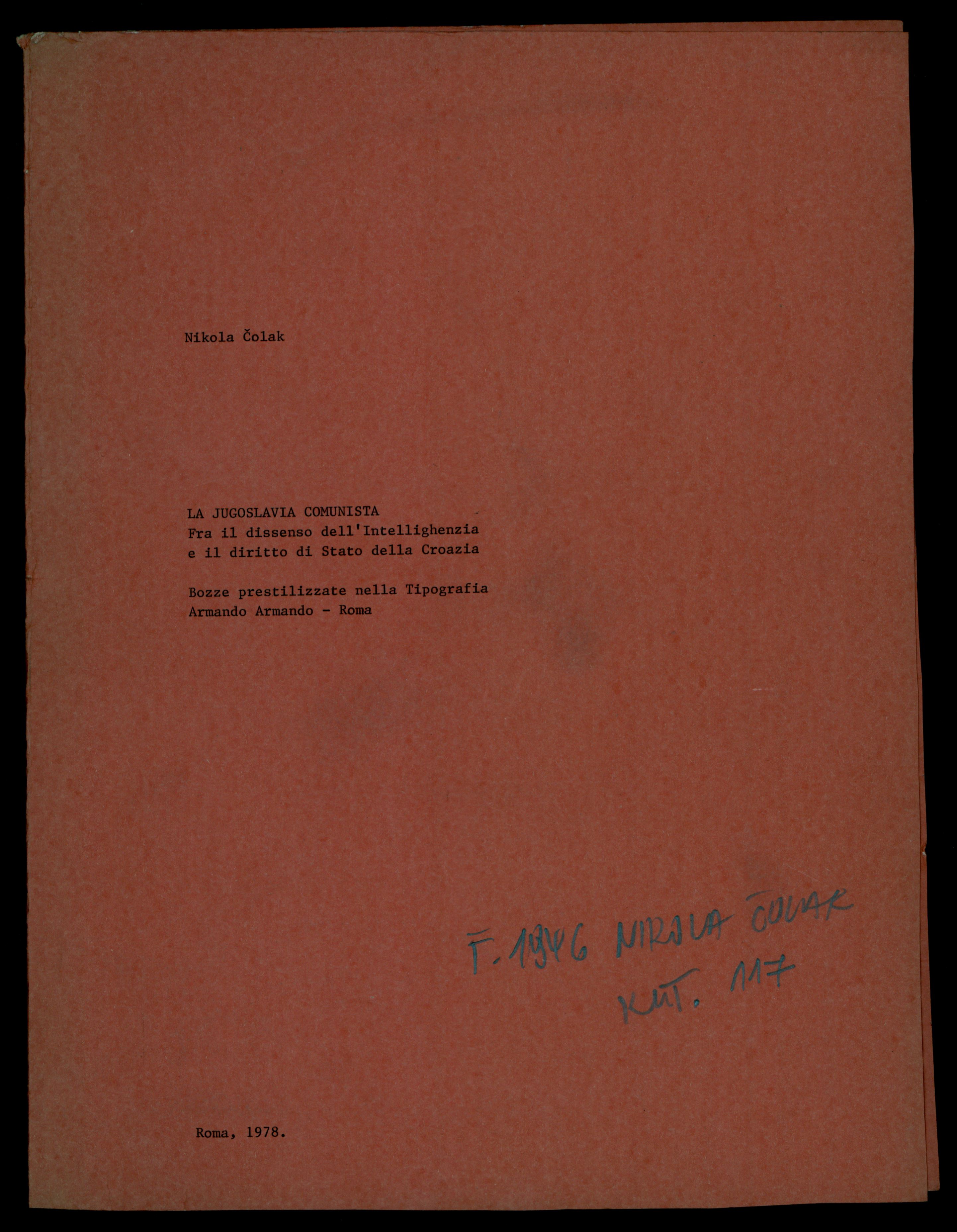

Čolak, Nikola. Communist Yugoslavia: between the dissent of intellectuals and the state-right of Croatia, in Italian, 1978. Manuscript

Čolak, Nikola. Communist Yugoslavia: between the dissent of intellectuals and the state-right of Croatia, in Italian, 1978. Manuscript

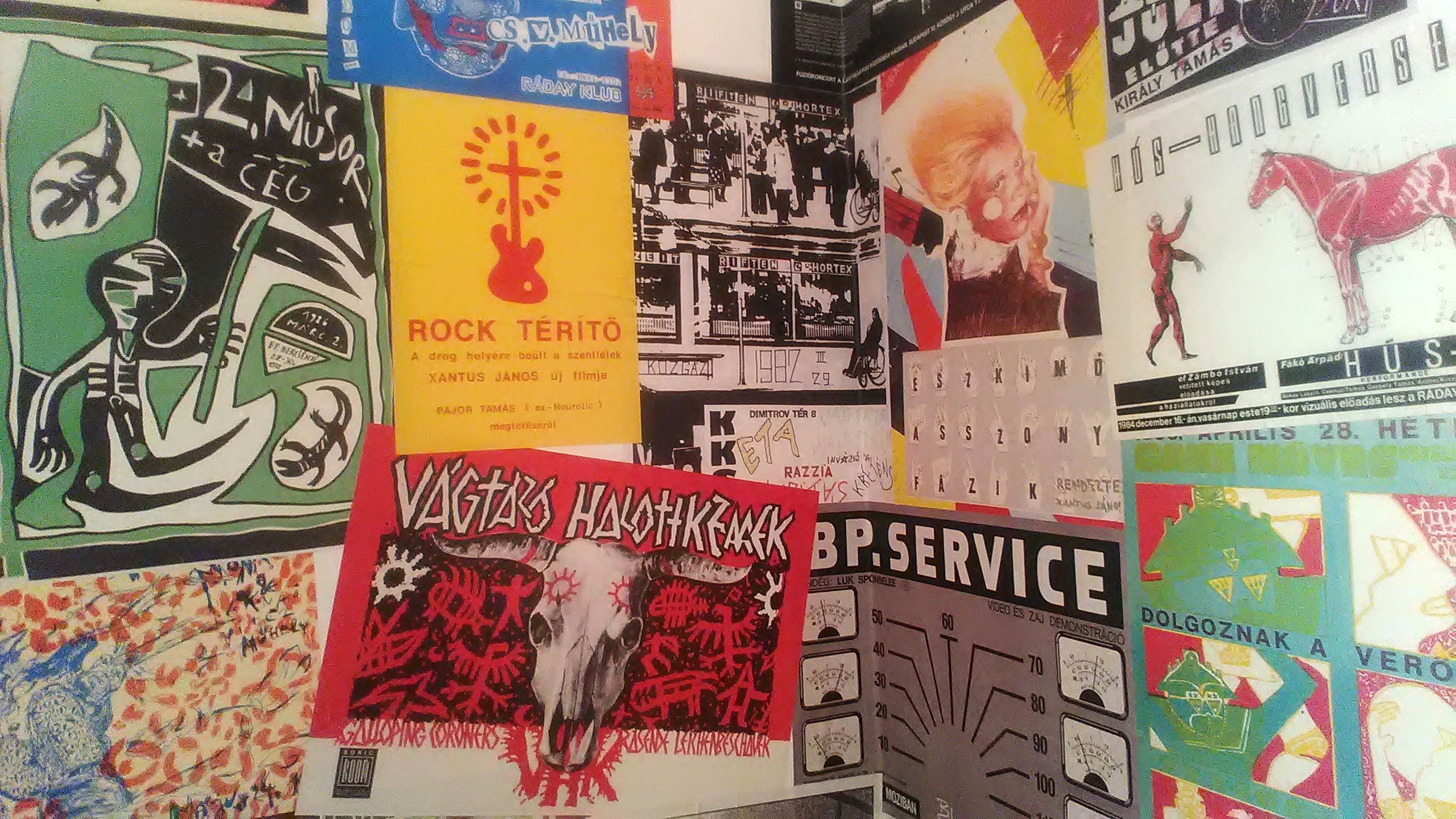

The Casual Passer-By Collection by the Bosnian-Herzegovinian conceptual artist Braco Dimitrijević consists of eight photographs and two posters (portraits) created in Zagreb and Belgrade in 1971. The photographs and posters (portraits) were the foundation of his three performances from the "Casual Passer-by" series staged in Yugoslavia. They were subversive performances in which the author hung portraits of chance passers-by in public spaces, otherwise intended for executives, in this way questioning established forms of communication in the public space of a socialist state.

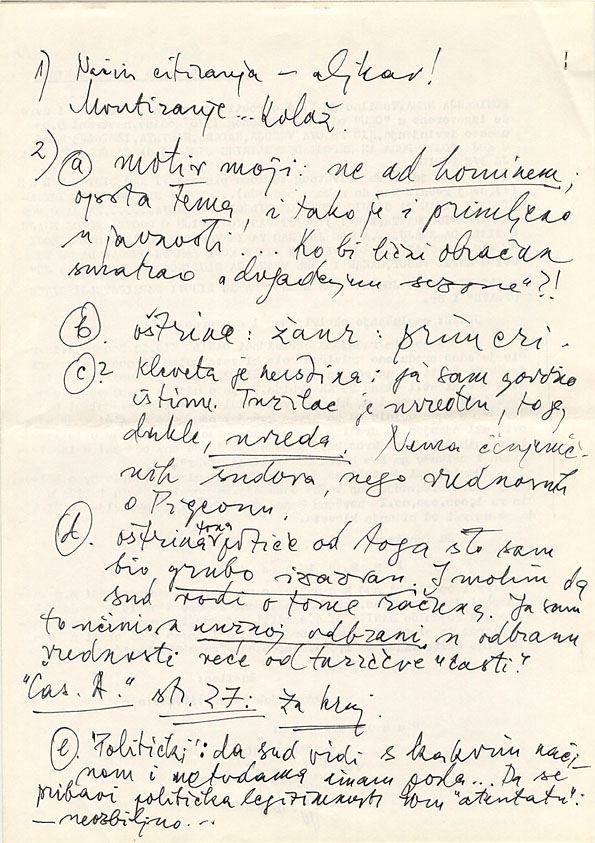

The court documentation in the collection shows that Kiš defended himself by explaining that his book was created as a gesture of a "legitimate and necessary defense, as a value greater than the prosecutor's honor: [a gesture] of my literary existence and my literary approach, as well as generally, as a fundamental defense against fatal and destructive judgements of a layman". In court, Kiš took the view that he was a writer and had the right to defend himself, using literature, against unfounded attacks on his work.

In a written statement delivered to the court, Kiš wrote: "The particular polemic sharpness of my book was, in addition, dictated not only by rough challenge and polemic fervour, but also by the literary genre itself: traditionally, polemic uses irony, sarcasm, ridicule, because it is a form of literary struggle." Kiš claimed further that polemics is a category of literature which an author can legitimately use and cannot be subject to claims of defamation. He listed a series of polemic writers and literature to try to defend his right to artistic expression. He also advocated for the view that literary controversy is actually a kind of public debate and is subject only to public judgment and literary history, not to be interfered with by the court.

In the end, the court accepted Kiš’s view, and acquitted him of the three counts of defamation. The court ruled that Kiš's response to Golubović in The Anatomy Lesson represents a "personal and subjective view to the prosecutor's conduct, and that this does not amount to facts serving to prove the truth, and thus it cannot be accepted as a charge for defamation.” The court also called for observing the broader context in which the book was created, which was in Kiš’s favour. However in 1979, after the lawsuit, Kiš left Yugoslavia embarrassed and disappointed.

Under the title „písačky“ (scribbles) Slovak writer Dominik Tatarka generally described his texts from the so-called Normalization period. Milan Šimečka commented that the word “písačky” contained “deep sorrow of a writer who had been writing in solitude and isolation, without the hope that his manuscripts would be ever a published book, printed, bound and read.” More specifically, “písačky” refers to texts collected in his later book “Písačky pre milovanú Lutéciu” that were created between 1976 and 1978 and were designed as love letters of an older writer to his young lover to Paris. Under the title “Písačky” some texts were published in 1979 already in the samizdat Petlice Edition by Ludvík Vaculík. Miroslav Kusý published about 50 copies of “Písačky” by samizdat in Bratislava but Slovak readers were said to show little interest because they perceived these texts as pornographic. Part of this samizdat edition by Kusý was confiscated by the State Security during one of house searches. In 1984, “Písačky” were published in exile by historian Ján Mlynárik in the Index Publishing House in Cologne. On 23 September 1986, Dominik Tatarka was awarded the Jaroslav Seifert Prize for “Písačky” by the Charter 77 Foundation in Stockholm. The Jaroslav Seifert Prize Committee consisting of Jiří Gruša, Milan Kundera, Antonín J. Liehm, Sylvie Richterová, Josef Škvorecký, Jan Vladislav, František Janouch and “in pectore” Ludvík Vaculík and Václav Havel, appreciated on these works by Tatarka that they “newly developed a genre of human monologue” and also “a bold testimony about a time and so far not reached depths of human mind”. Tatarka learned that he was awarded the prize from the Voice of America broadcasting on the very day. “Písačky” were officially published after 1989 in an edition by Ján Mlynárik (1998, together with “Letters to Eternity” and “Alone against the Night”) and by Oleg Tatarka as “Písačky pre milovanú Lutéciu” (1999, 2003, 2013).

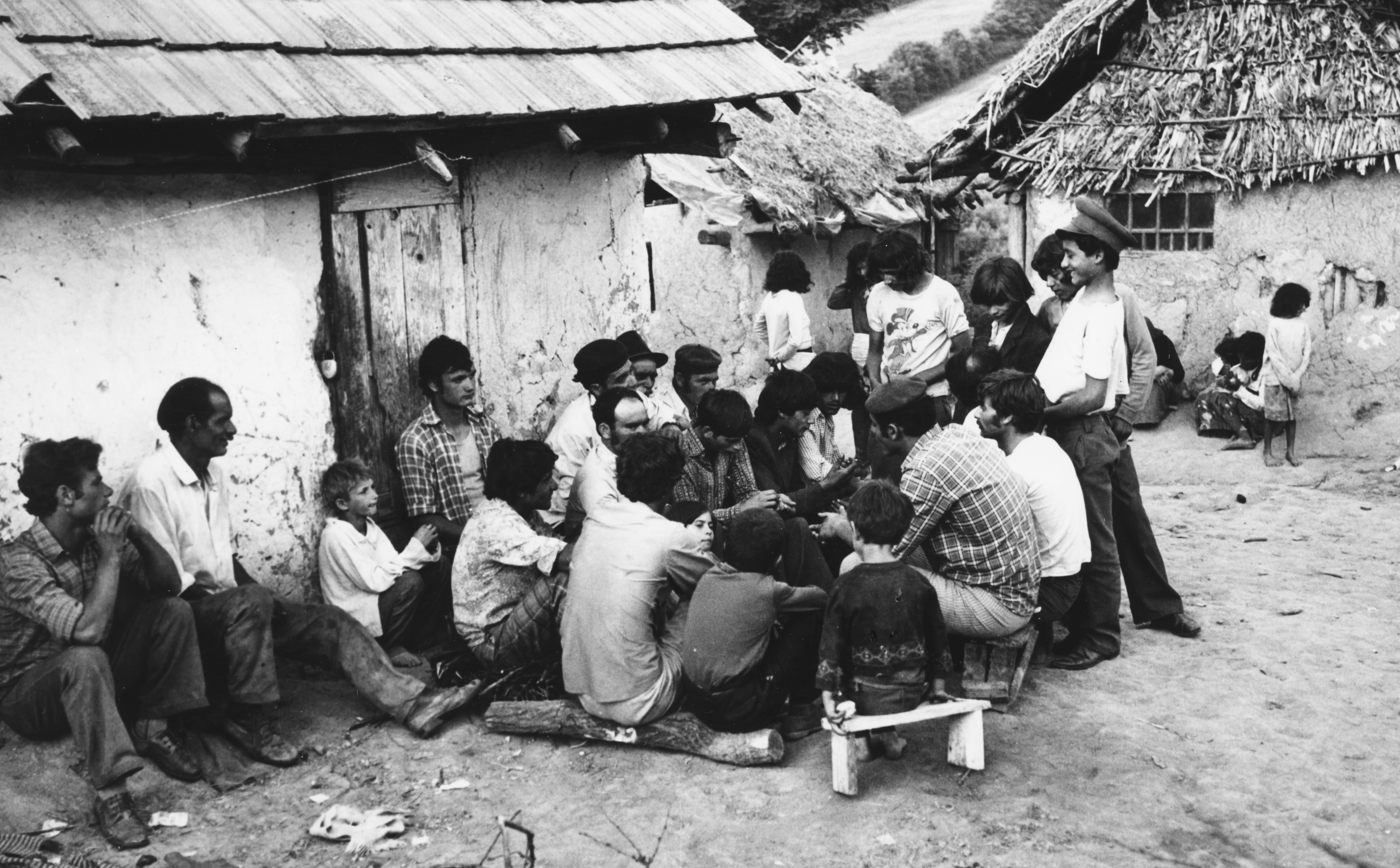

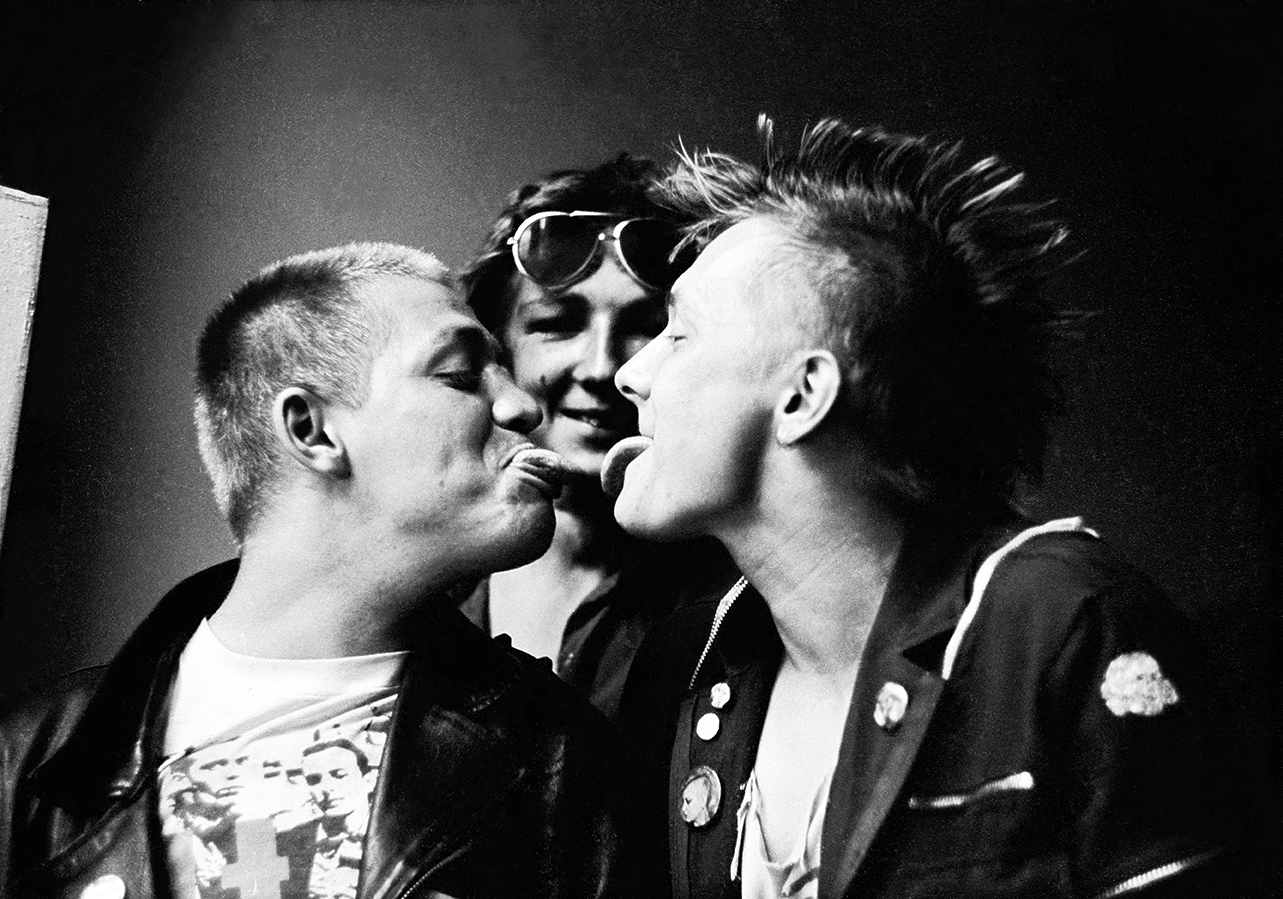

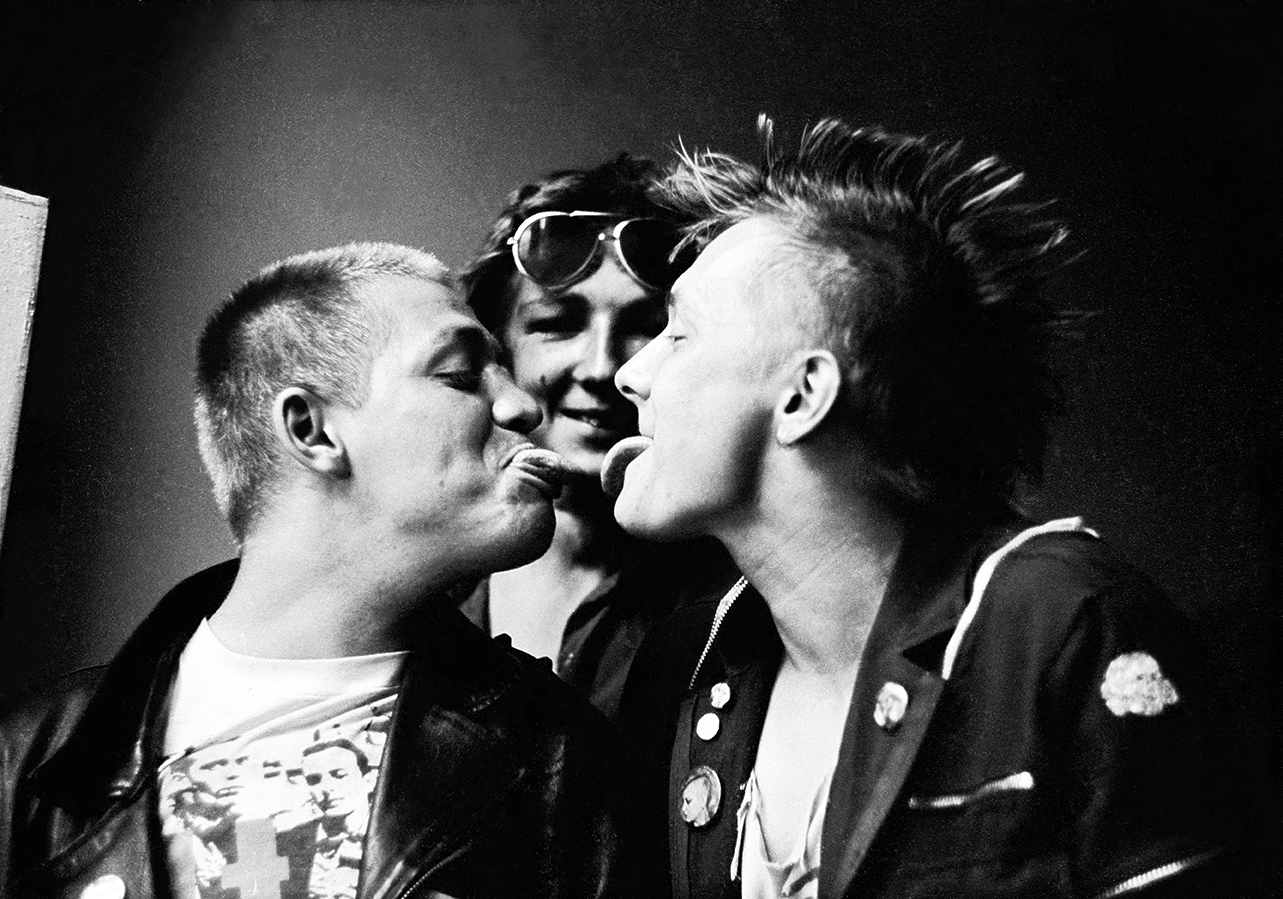

Punk w Polsce Ludowej zaczął się w 1978 roku, a jednym z miast, w których szybko zdobywał popularność była Warszawa. Specyfiką pierwszych lat warszawskiego punku były jego bliskie związki ze studenckimi klubami i galeriami, w których rozkwitała sztuka performansu, mail artu, poezji konkretnej. Kolekcja punkowej fotograficzki Anny Dąbrowskiej-Lyons zawiera ziny, zdjęcia i wycinki z gazet, zbierane od 1978 do około 1982 roku. Najciekawsze z tych materiałów opublikowane zostały w 1999 roku w albumie „Polski punk”. To z jednej strony dokumentacja pierwszej fali punku w Warszawie, z drugiej – oryginalne, artystyczne fotografie, kolaże i grafiki, łączące zachodnie wpływy punku i nowej fali z poetyką futuryzmu, dadaizmu i konceptualnymi teoriami lat siedemdziesiątych.

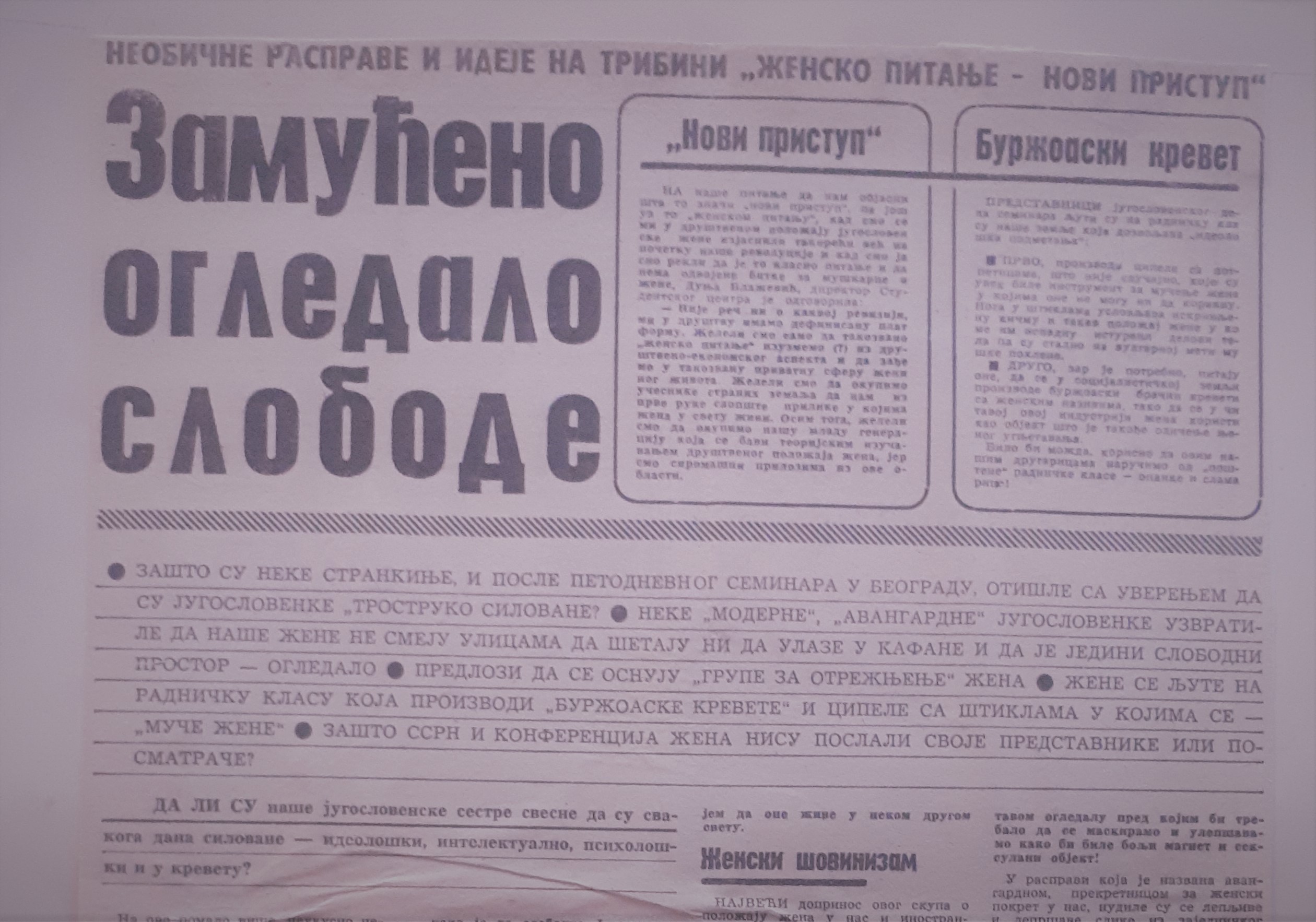

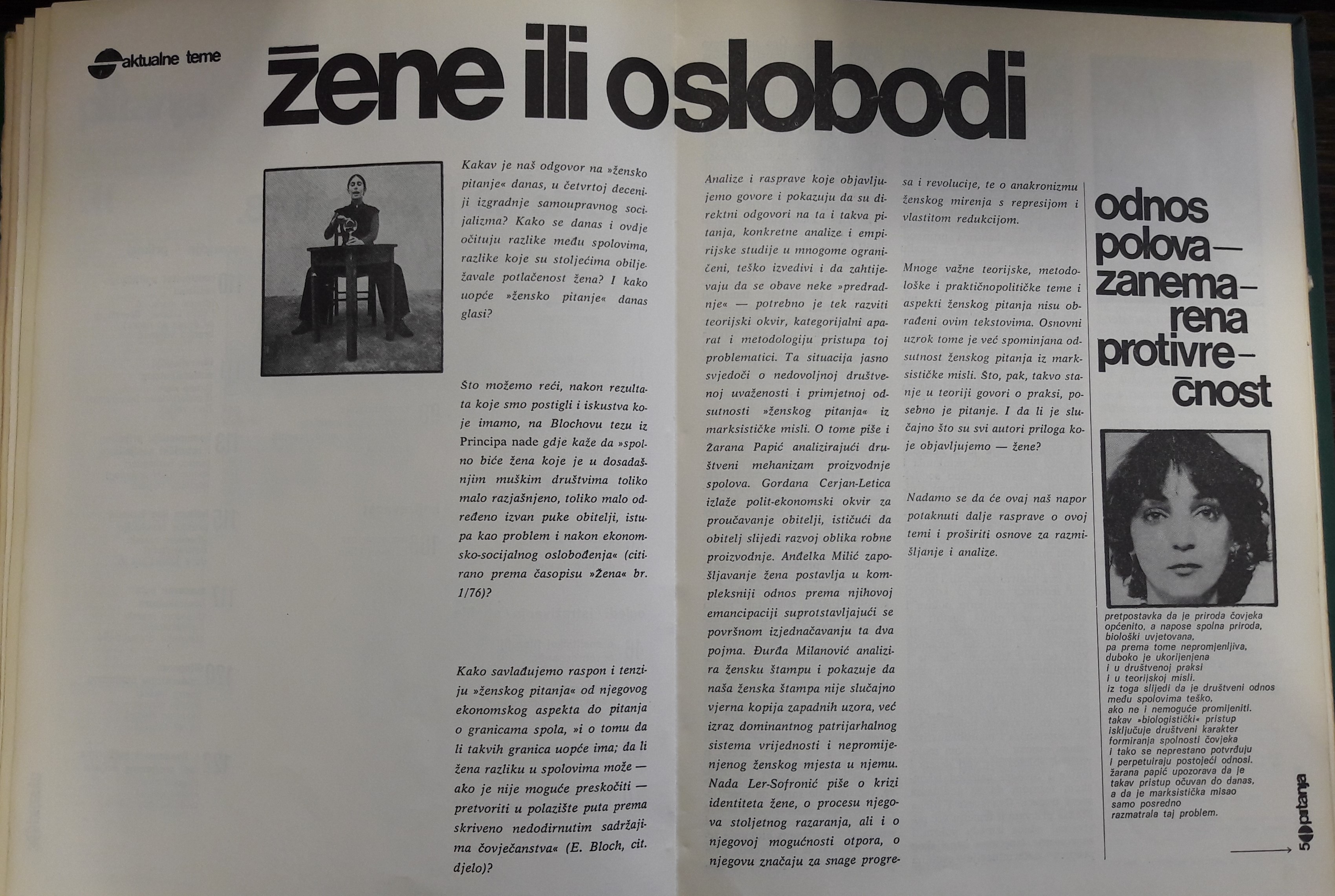

In 1978, Lydia Sklevicky edited the "Current Topic" section in the journal Pitanja (year 10 (1978), no. 7/8) and entitled it "Women, or about Freedom." Sklevicky wrote an introduction to the issue's topic in which one of the questions the articles should answer was: What is our response to the "women’s question" today, in the fourth decade of self-management socialism? Later in the text, she gave a partial answer to this question, and also a critique of Yugoslav socialism, claiming that there is no developed theoretical framework in Yugoslavia, nor a categorical apparatus and methodology for approach that would allow researchers to deal with this question, and she concluded that: "This situation clearly demonstrates inadequate social respect and the noticeable absence of the "women’s question" in Marxist thought (Sklevicky 1978, 4).

Besides Sklevicky, who edited the issues topic and wrote an introduction to it, articles were published by Žarana Papić ("Gender Relations - Neglected Discrepancy"), Nada Ler-Sofronić ("The Odyssey of Women's Human Identity"), Gordana Cerjan-Letica (“Indications of the Socialist Mercantile Production of the Family“), Anđelka Milić ("Employment of Women and Their Emancipation") and Đurđa Milanović ("Women's Press – the Industry of Happiness").

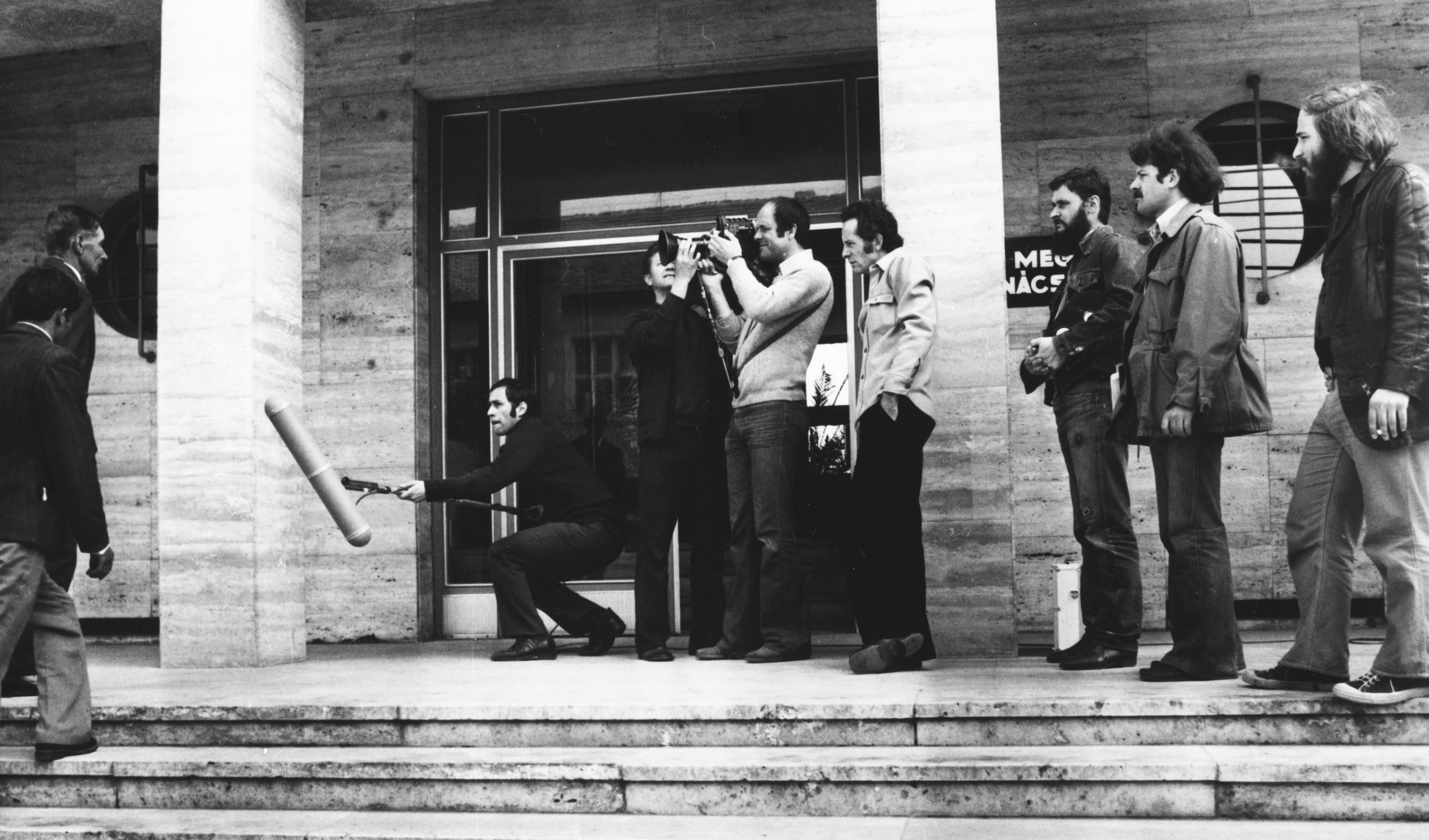

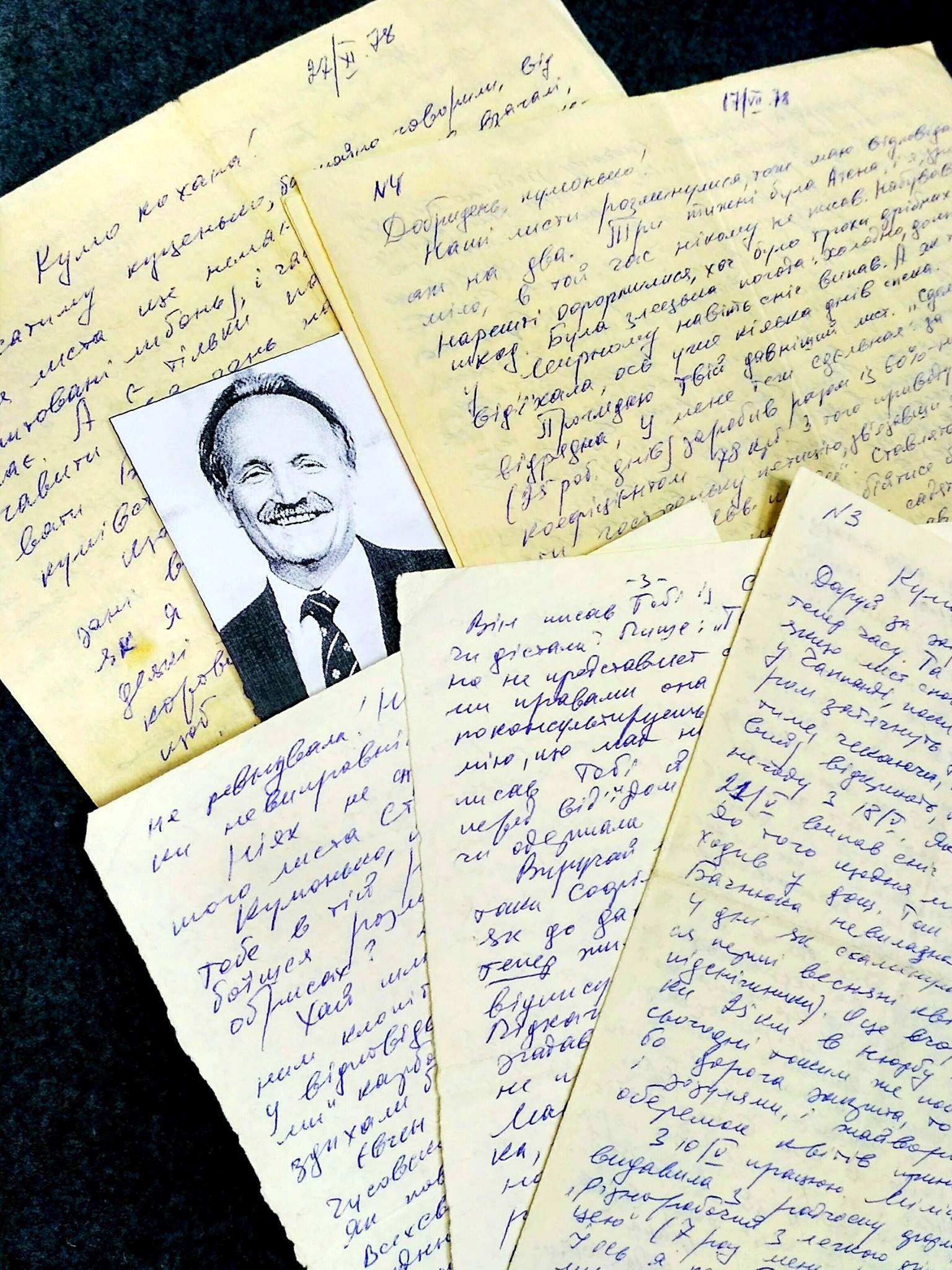

Viacheslav Chornovil’s three letters sent to Iryna Stasiv-Kalynets in 1978 were donated to the museum-memorial along with much of her correspondence from her time in exile in the Chytynsk region of Siberia, in a village not far from the Chinese border. These letters penned by her close friend, fellow dissident and journalist Chornovil, while he served out his own lengthy sentence in Yakutia, are particularly illuminating about the conditions in which they lived. Curators of the collection note that this is a unique item, as its vibrant and accessible language brings to life Chornovil’s experiences in the camps, and later in exile, the changing circumstances of his day-to-day life, and ongoing discussions over the legality of the work regimen with correspondents. He and Stasiv-Kalynets also discussed Chornovil’s concerns over the agendas of likely well meaning, but unknown parties from the Ukrainian diaspora in North America. This was most probably tied to the fact that one such person, Yaroslav Dobosh, a member of a nationalist youth organization, came to Ukraine from Belgium to meet with dissidents, triggering one of the gravest campaigns of surveillance and arrests against Ukrainian dissidents—called Operation Bloc. These three letters chart a year in the life of political prisoners in internal exile in the Soviet Union and once translated and published are expected to provide a unique and illuminating window into this world for researchers, students and the general public.

The Charter 77 Foundation was founded in Stockholm in 1978 to support persecuted and imprisoned chartists and dissidents in Czechoslovakia, as well as to support opposition activities in the fight for human rights and civil liberties. The Charter 77 Foundation was led and organised by Frantisek Janouch.

Fotografia wykonana przez Tomasza Sikorskiego przedstawia fragment wystawy Forma i dźwięk, która prezentowana była w dniach 20-25 marca 1978 roku w Galerii Mospan. Na zdjęciu widoczni są między innymi Dorota Mroczko i Paweł Kwiek. Wystawa przedstawiała prace studentów pracowni rzeźby prof. Jerzego Jarnuszkiewicza na Akademii Sztuk Pięknych w Warszawie, zaś wśród autorów znaleźli się Krzysztof Bednarski, Hanna Roszkiewicz, Marek Sarełło, Tomasz Sikorski, Roman Woźniak, a także – spoza grona studentów pracowni Jarnuszkiewicza – Jacek Malicki. Nietypowy jak na pracownię rzeźby temat formy przestrzennej i dźwięku był efektem współpracy studentów z awangardowym muzykiem i kompozytorem Andrzejem Bieżanem. Pod jego opieką studenci podjęli temat powiązań między formą a dźwiękiem. Efekty zaprezentowane zostały w Galerii Mospan.

Seria performansów duetu KwieKulik pod hasłem „Działania na głowę” odbyła się w czasie festiwalu „Body Performance” w lubelskiej galerii Labirynt w 1978.W ramach jednego z działań, znanego dzięki ikonicznej fotografii, Przemysław Kwiek umył twarz i nogi w misce, w której, przez wycięty otwór, wystawała głowa jego artystycznej i życiowej partnerki Zofii Kulik.KwieKulik już wcześniej używali w swoich działaniach głów i twarzy, modeli i własnych. W 1971 roku wraz z zaprzyjaźnionymi artystami przeprowadzili Grę na twarzy aktorki. Była to rejestrowana kamerą procesualna gra wizualna. Wzięła w niej udział znana masowej publiczności z hitowego serialu Janosik Ewa Lemańska. Znajdujący się poza kadrem artyści wykonywali na jej twarzy kolejne posunięcia, poprzez plastyczne gesty. Każdy gest miał nawiązywać do poprzedniego i otwierać się na następny. Malowali ją farbą, oklejali taśmą klejącą i krepiną, przyklejali kolorowe patyki, robili na niej małe rzeźby z plasteliny. Jeden z uczestników wsadził aktorce w zęby kawałek szyby i położył na niej zapalony papieros. Pełny opis serii performansów z 1978 roku został zamieszczony w monumentalnej książce podsumowującej działalność KwieKulik (z 2012 roku):

„W części pierwszej widzowie przed wejściem na salę zostali poproszeni o włożenie sobie za ucho małych czerwonych chorągiewek […] Wchodząc do sali, widzowie zobaczyli Kwieka i Kulik z głowami uwięzionymi w siedziskach dwóch krzeseł. W drugiej części Kulik siedziała na podłodze z głową wystającą z dna miski. Po wlaniu do miski wody, Kwiek umył twarz, ściągnął koszulę, umył się pod pachami, wreszcie zdjął buty, skarpetki i umył nogi. Kwiek dolał więcej wody, aby jej poziom był powyżej ust, a poniżej nosa Kulik, tak aby mogła oddychać, lecz nie mogła mówić. Przystawił jej do potylicy ostry szpic noża i zaczął krzyczeć: „No powiedz coś, kurwo, powiedz..., nie możesz, co...?!” W części trzeciej widzowie zobaczyli Kwieka i Kulik siedzących na krzesłach z kubłami na głowach (w dnach kubłów były otwory). Poproszeni wcześniej dwaj artyści (Janusz Bałdyga i Łukasz Szajna) zaczęli krążyć wokół artystów, wrzucając do kubłów śmieci wyjęte wcześniej z pojemnika znajdującego się na korytarzu galerii.”Tytuł perofmansu został użyty w tytule wystawy zbiorowej warszawskiego Muzeum Sztuki Nowoczesnej z 2015, prezentującej nowe zjawiska w polskiej sztuce. Tytuł został tam uogólniony jako metafora „działań na głowę widza, jak i użycia głowy-umysłu jako narzędzia do kalibrowania tego co widzialne i niewidzialne wokół nas”.Kadr ze zdjęcia Kwieka myjącego twarz w misce z głową KuliK trafił też na okładkę książki podsumowującej działalność duetu

Źródła:

KwieKulik. Zofia Kulik & Przemysław Kwiek, red. Łukasz Ronduda, Georg Schöllhammer, Warszawa/Wrocław/Wiedeń 2012.