The Andrei Pandele private collection is the most significant testimony in pictures, mainly black and white, to the demolition of historic monuments and districts in the Romanian capital in the period of late communism. Together with photographs that are essential for the preservation of the memory of a mutilated city and a vanished cultural heritage, the collection also includes a series of images capturing aspects of the degradation everyday life throughout the profound crisis of the 1980s. These suggest both the absurdity of the policies of the Ceaușescu regime and the grotesque mutations in the everyday routine of ordinary people to which these policies gave rise.

The private collection of Tamás Csapody (1960–) includes documents related to movements for the reform of the compulsory military service and the introduction of alternative civilian service. Refusal to perform military service was an illegal act in the countries of the Warsaw Pact. Csapody’s collection, as the only collection focusing this specific topic, contributes to remembering the stories of people who were penalized by the laws of the Kádár regime because of freedom of thought, conscience, and religion.

Ladislav Mňačko (1919–1994), a Slovak writer, poet, playwright and journalist, is well known mainly as the author of the famous book Jak chutná moc (The Taste of Power; 1967), which describes the practices of Communist functionaries, as well as several other works which were published in Czechoslovakia before 1968. His works written in Austrian exile after 1968 are less well known. This also applies to the play Tschistka (Purge). This satirical play describes the practices of an omnipotent secret police in a totalitarian state, which in the end becomes the victim of its very own terror. It was produced by the Austrian broadcaster ORF as a radio play in 1983 and directed by Fritz Zecha. The play was also produced by the Slovak National Theatre in 1993. The Austrian edition of this play from 1980 is held in the Ladislav Mňačko Collection in the Literary Archive of Museum of Czech Literature.

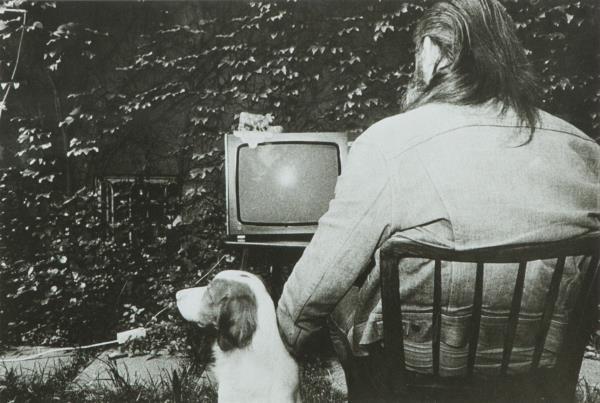

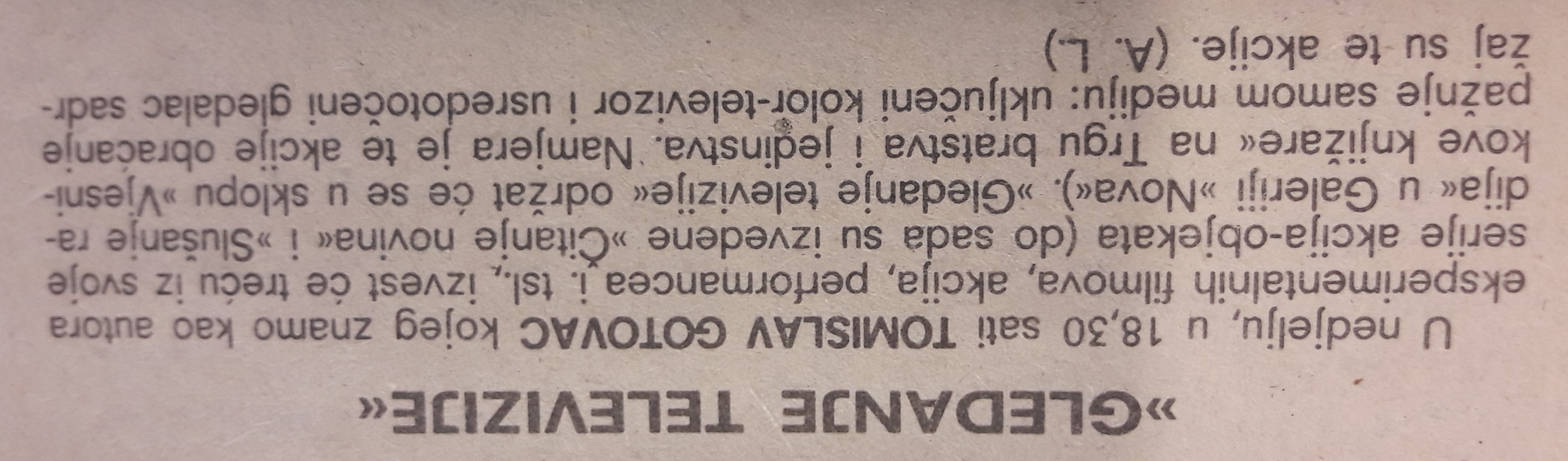

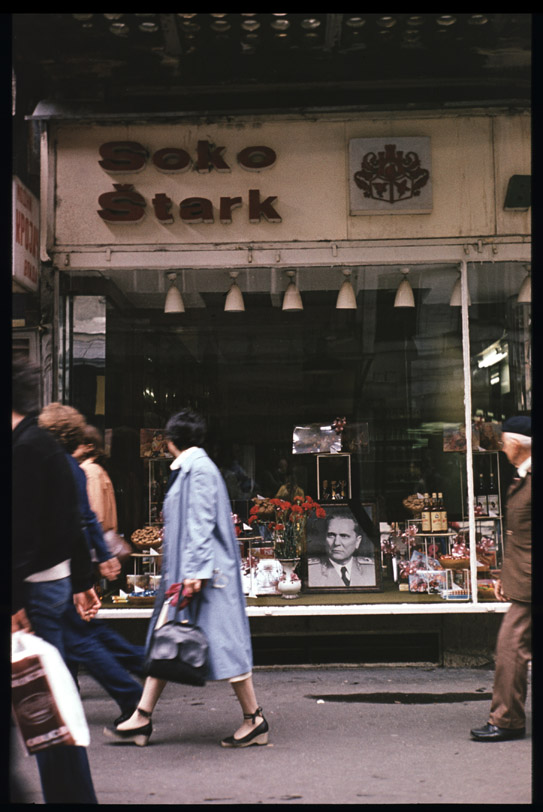

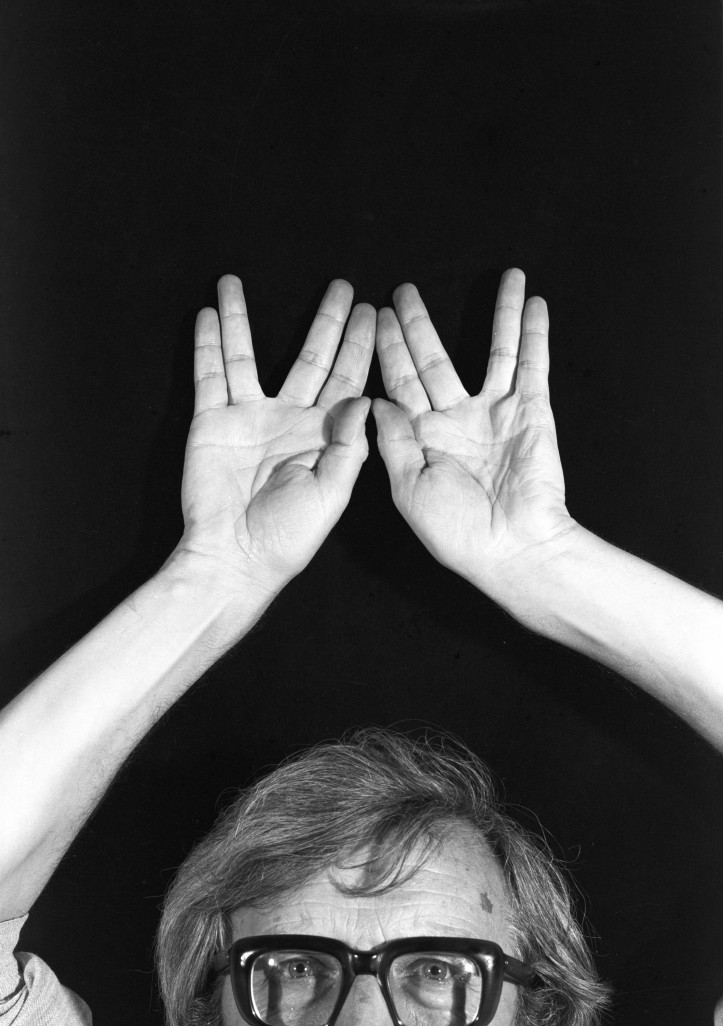

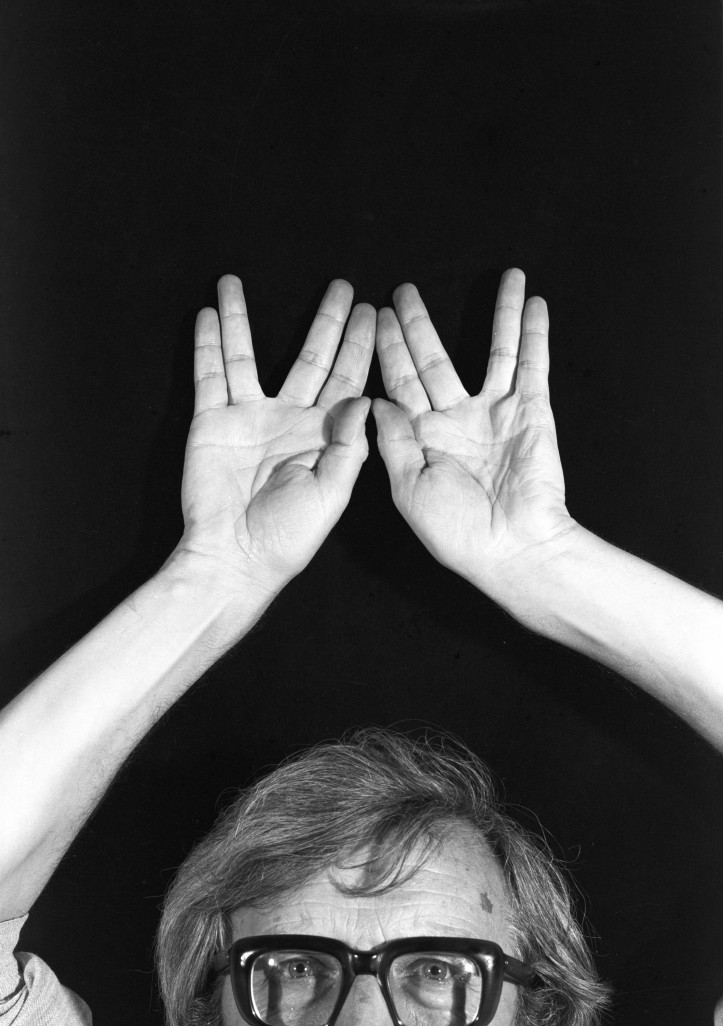

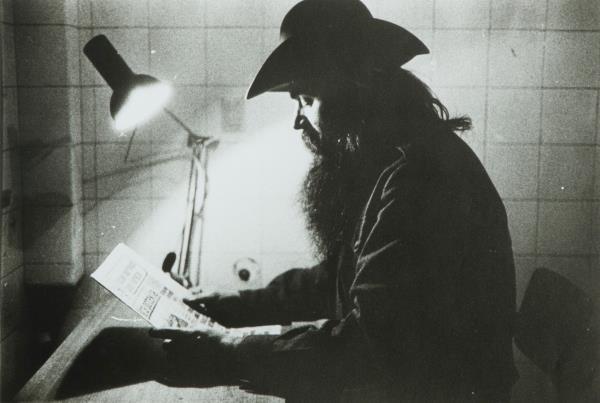

The first performance from the Homage to Josip Broz Tito is “Reading the Newspaper” by Tomislav Gotovac, staged in the New Gallery in Mihanovićeva street 28 in Zagreb at 6 p.m. on February 12, 1980. The performances were photographed by Milisav Mio Vesović and Ognjen Beban.

This was a reprise of the work Gotovac performed in Amsterdam in 1979, and the beginning of the Homage to Josip Broz Tito cycle. According to journalist Ana Lendvaj, Gotovac wanted to show how ˝the newspapers have the structure of a drama and that reading literally every printed letter in a newspaper is a dramatic performance in which every reader is free to invent” (Lendvaj, “Reading the Newspaper,” 1980). Gotovac used subversive action in his performance, because at this point the audience did not know how to criticize the media space in Yugoslavia.

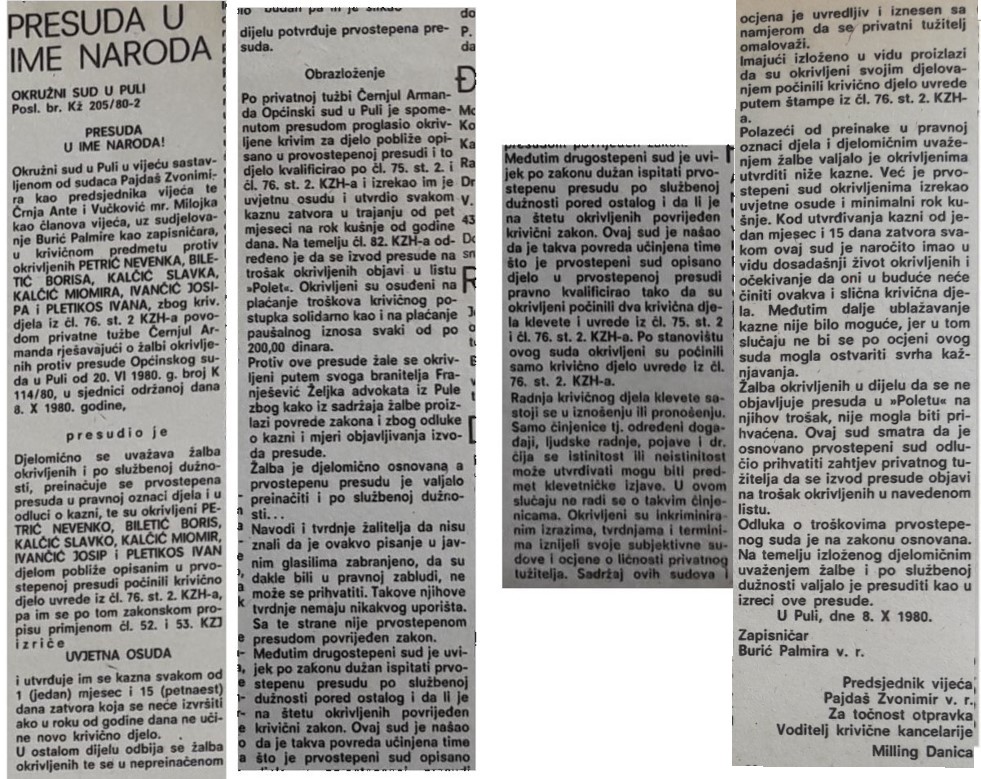

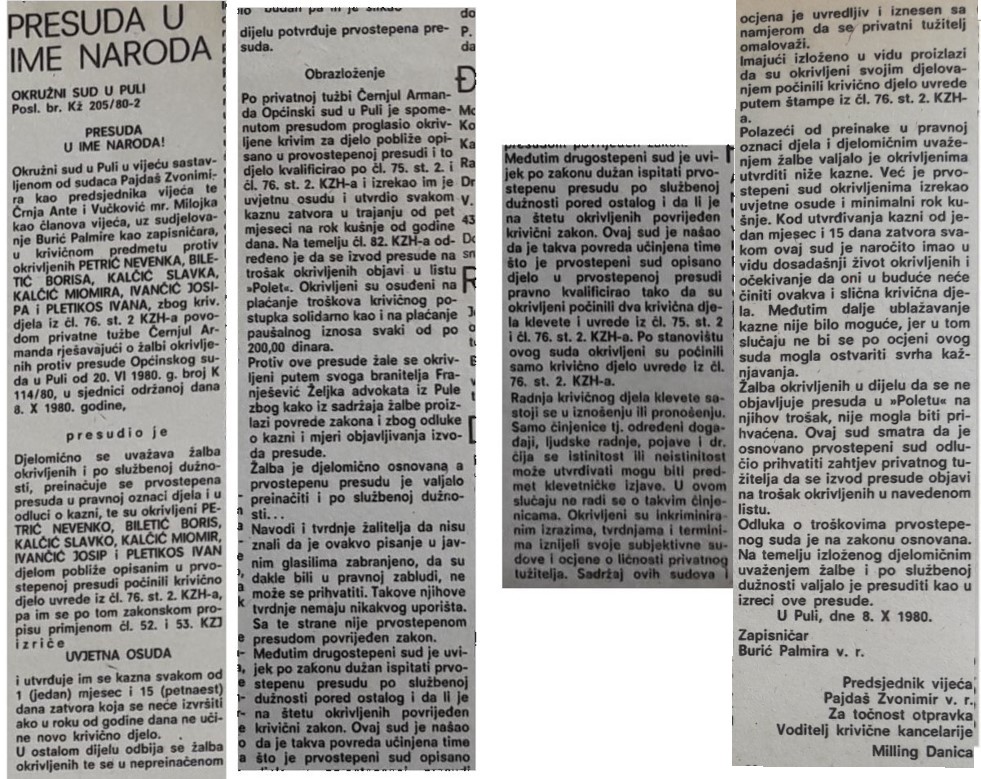

The "IBOR Case" was mostly covered by journalist Armando Černjul, writing for the Istrian edition of the daily newspaper Evening Paper and Polet. It was his article in Polet ("Enough with crude disinformation," February 6, 1980) that prompted IBOR's editorial board to react with another article in Polet ("Photogenic falsifier," February 19, 1980), in which they stated that Černjul has a "Zhdanovist temper,“ that he is a "press-agent in the service of power," and a philistine (Polet, February 19, 1980). Černjul filed a private lawsuit for slander and defamation against the IBOR's editorial staff. The court dismissed the part of the suit pertaining to slander, but ruled against members of the IBOR's editorial board (Nevenko Petrić, Boris Biletić, Slavko Kalčić, Miomir Kalčić, Josip Ivančić and Ivan Pletikos) for defamation and assigned each "a month and a half suspended sentence and one year of probation." At the request of the plaintiff (Černjul), and pursuant to the court’s decision, the verdict was published in Polet (5 November 1980, p. 2).

The copy of the icon of the Bakócz Chapel from the Esztergom basilica from the eighteenth century illustrates a profound tradition of religious handmade replicas. The collection includes numerous artworks made by nuns who copied holy objects from the seventeenth through the twentieth centuries. The importance of these works in religious culture is that they were thought to transmit the “sacrament.” Their preparation was time-consuming and needed a lot of patience. Motifs in the decoration of the relics and the styles of painting the miniature sacred images were produced from the seventeenth to the nineteenth centuries by the Sisters of Saint Clara, the Sisters of Saint Ursula, the Congregation of Jesus, and the Order of Saint Elisabeth. The popularity and the survival of the artwork by nuns was helped by students in schools run by religious nuns from the nineteenth century to the twentieth. These students learned the tricks of hand-crafting, and this knowledge was passed on to family members and their servants. The servants of the schoolmistresses, in turn, mediated the culture of the nuns to the peasants. The nuns’ works in the churches were used in religious ceremonies. However, talented peasant women often copied their motifs.

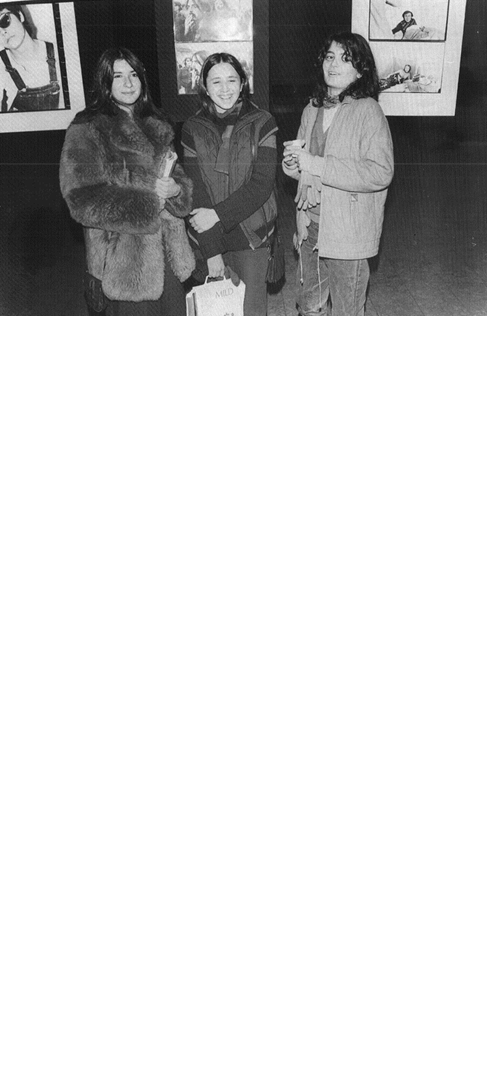

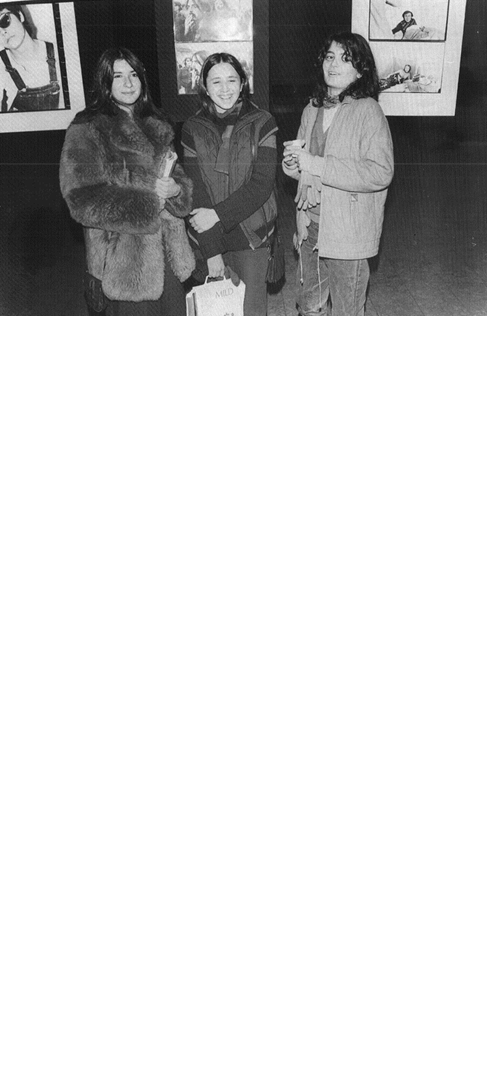

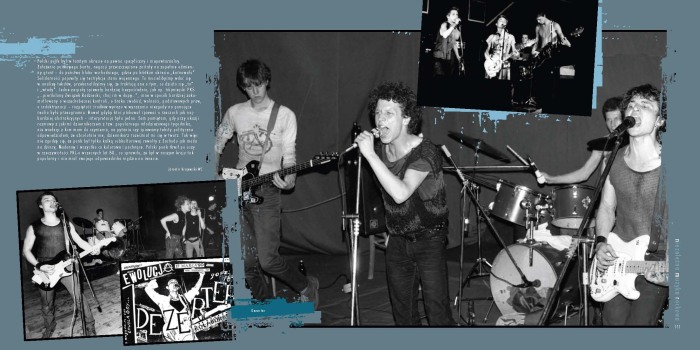

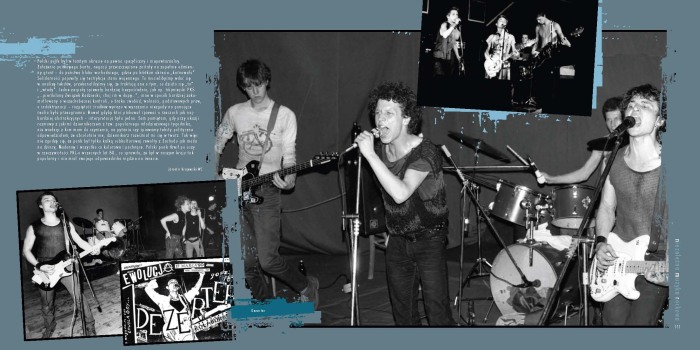

Goran Pavelić Pipo staged his first solo exhibition at the Student Centre Gallery in Zagreb in 1980. The opening of the exhibition coincided with the beginning of the new wave, so Pavelić's photographs featured the leaders of the new wave, such as Branimir Johnny Štulić, Davorin Bogović, Jure Stublić, or the band Buldožer.

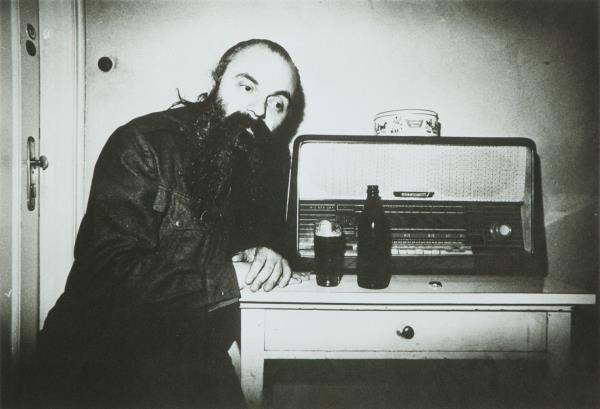

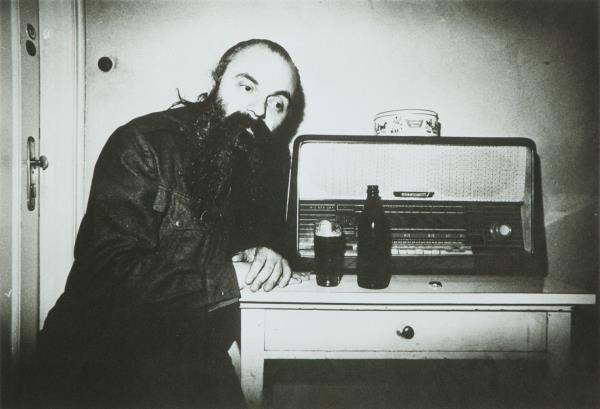

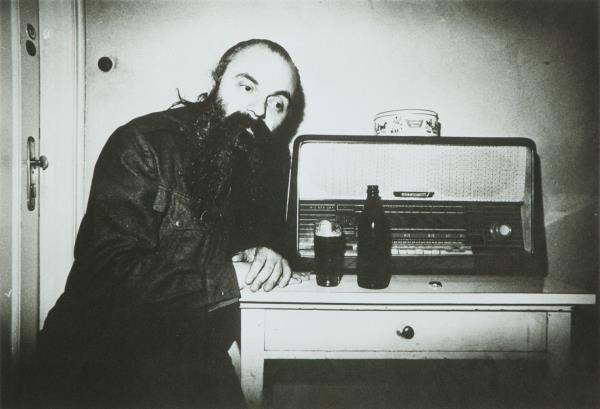

The second performance from the Homage to Josip Broz Tito cycle is "Listening to the Radio" performed by Tomislav Gotovac in the New Gallery New in Mihanovićeva street 28 in Zagreb from 5 p.m. to 6 p.m. on April 1, 1980. The performances were photographed by Milisav Mio Vesović and Ognjen Beban.

It is the continuation of the Homage Tito cycle in which Gotovac used the mass communication media, in this case radio, to stress the psychosis surrounding the anticipation of the death of Yugoslav leader Tito. The artist also used subversive activity in his work, in which he did not criticize the regime, but encouraged people to think.

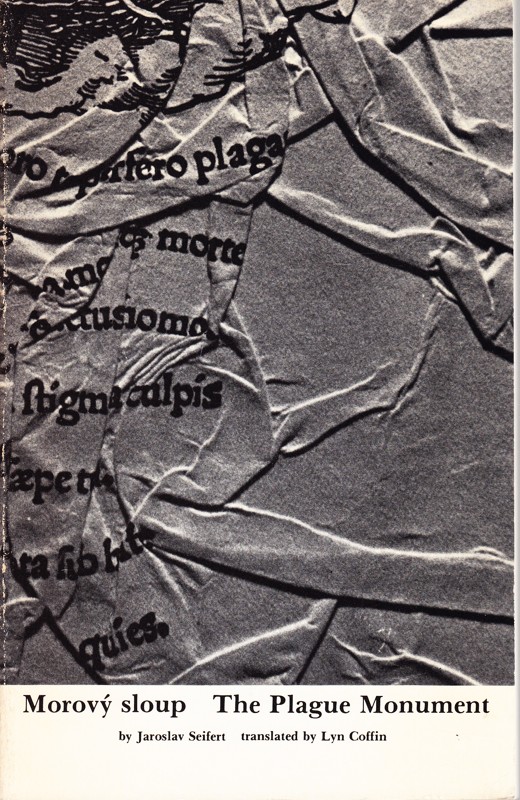

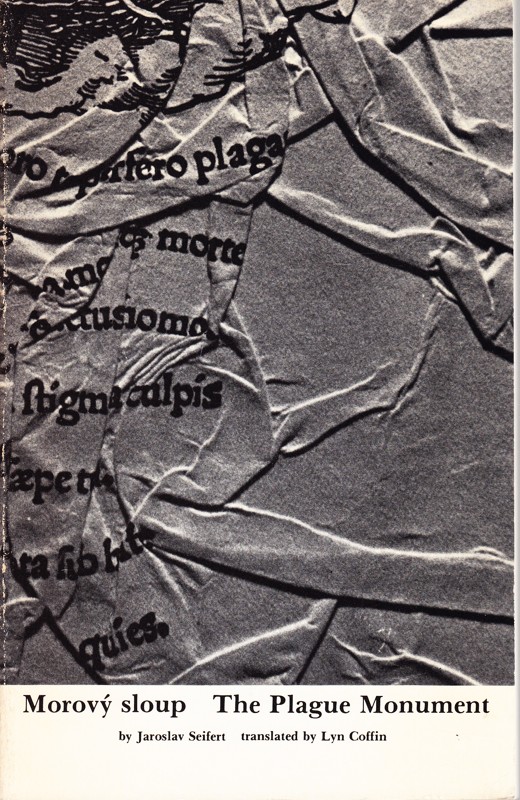

Czech poet Jaroslav Seifert was an example of an author affected by the communist regime, mainly after the Soviet invasion of Czechoslovakia in 1968. Although he was a designated “National Artist”, and was awarded many state prizes, he was not allowed to publish, with some exceptions, especially during the 1970s. Thus, his poems were often illegally transcribed as a samizdat or published in exile. This was also the case of his collection of lyrical poems “Morový sloup” (The Plague monument) written in the late 1960s and early 1970s, thus at the beginning of the so-called “normalization”. The collection “Morový sloup”, which also reflected the actual political situation in Czechoslovakia, was published in Washington by the Czechoslovak Society of Arts and Sciences in 1980. This edition was illustrated by Czech artist Jiří Kolář and translated by American poet Lyn Coffin.

Stocznia Gdańska im. Lenina, Michał Guć, Gdynia 2017 (tekst nieopublikowany, udostępniony przez autora w lipcu 2017 roku).

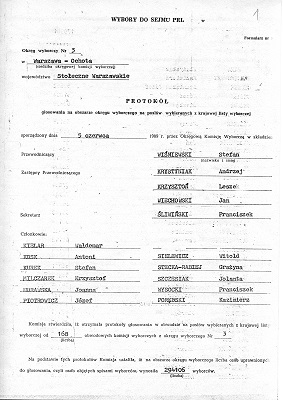

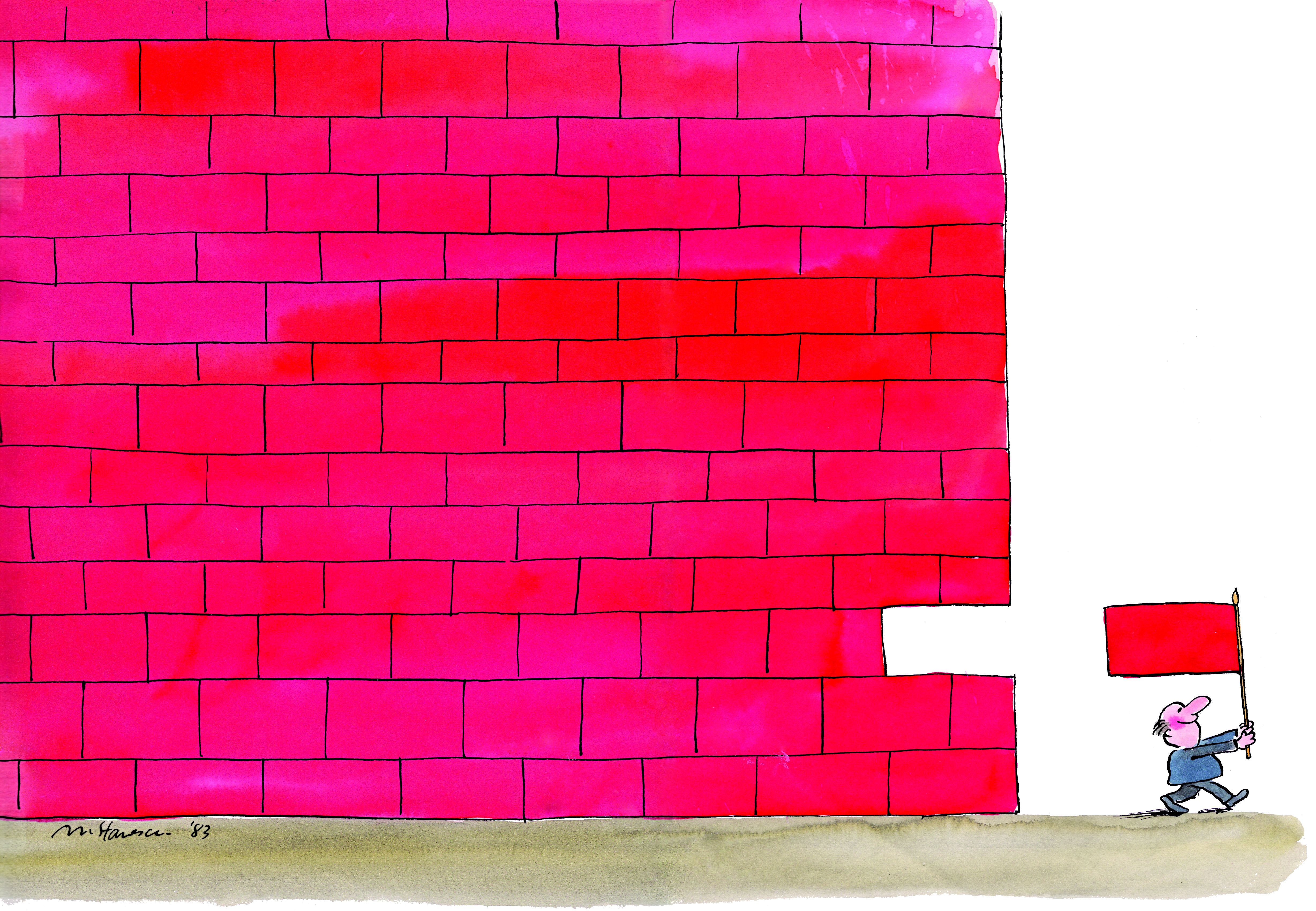

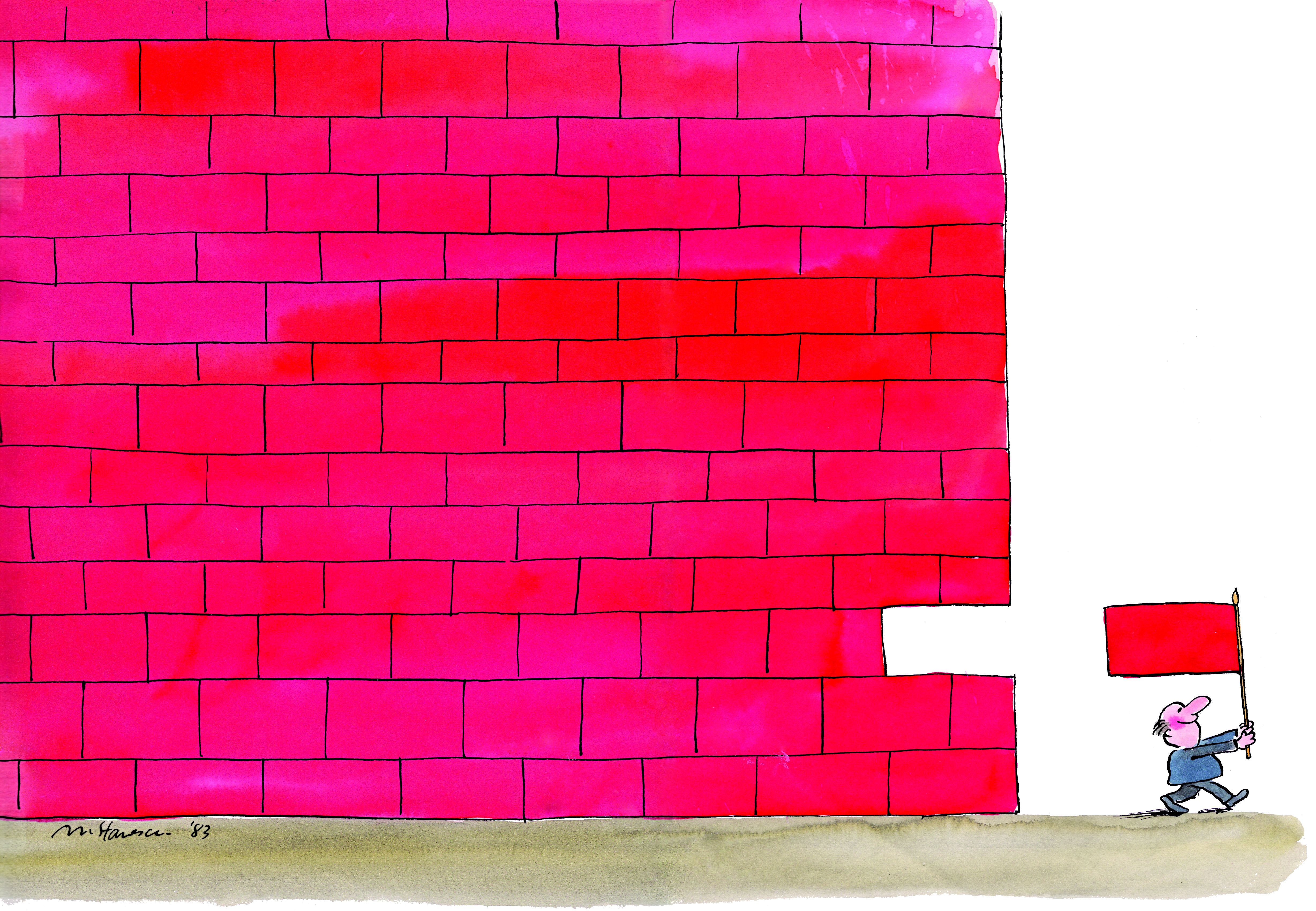

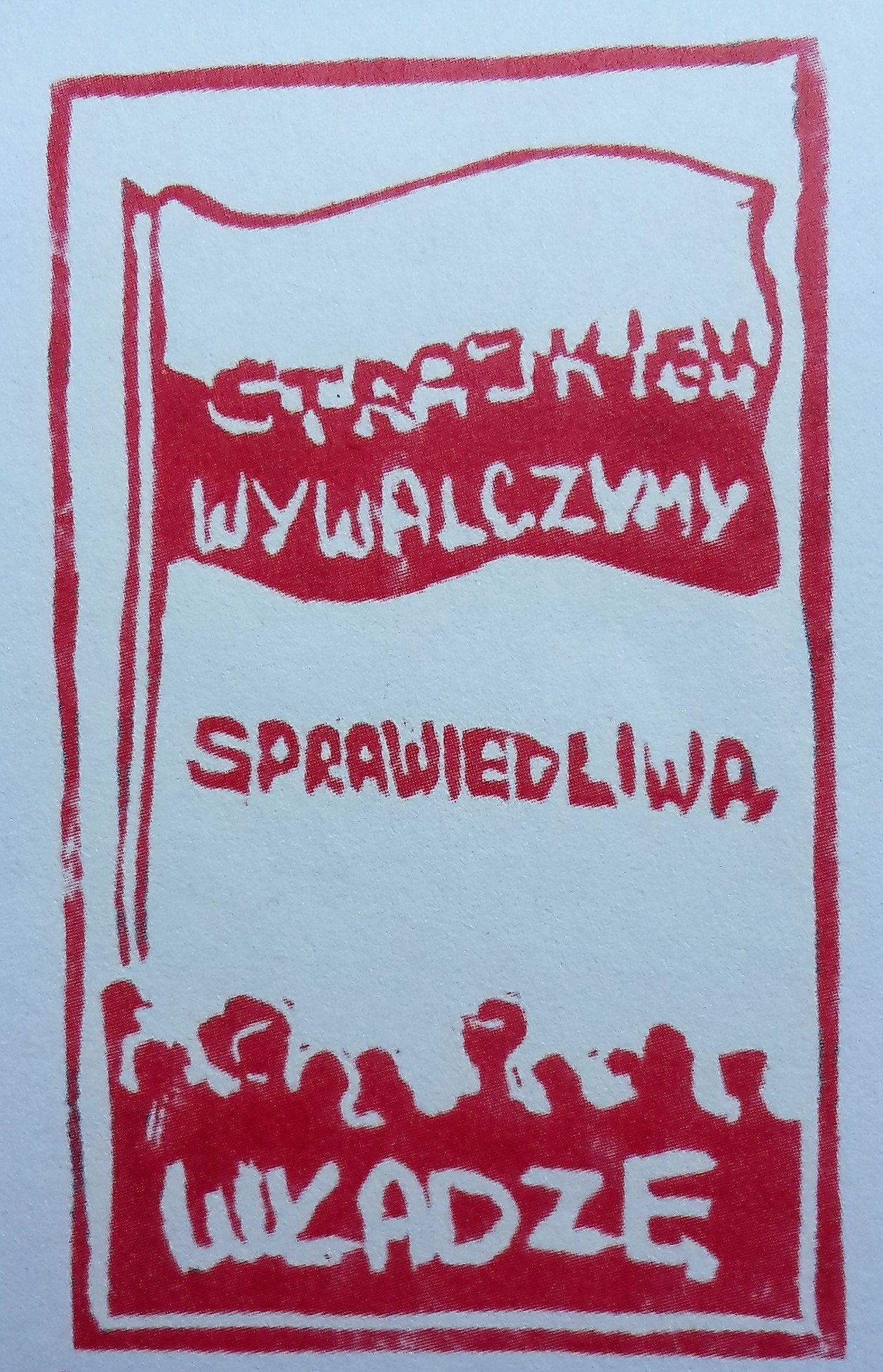

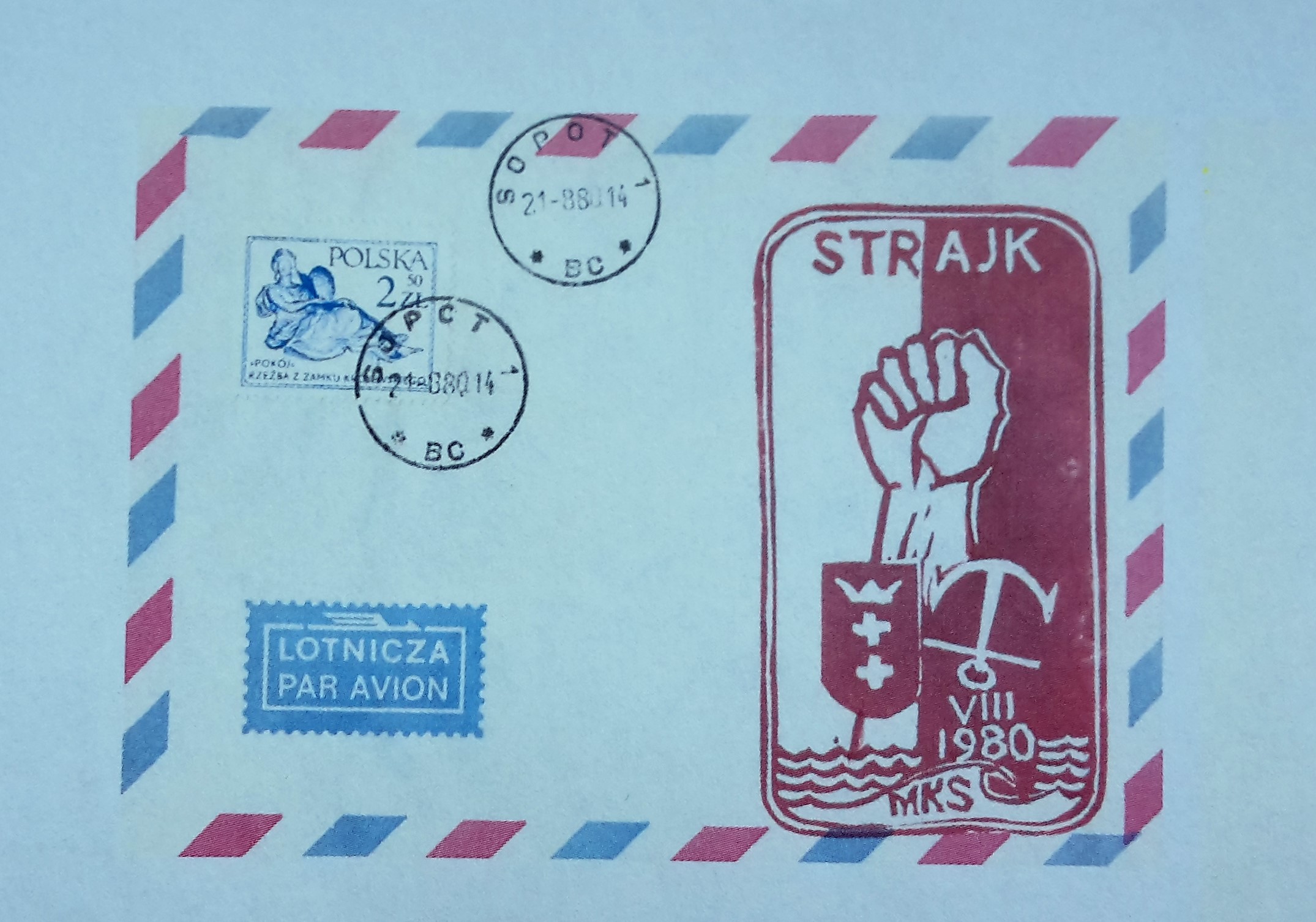

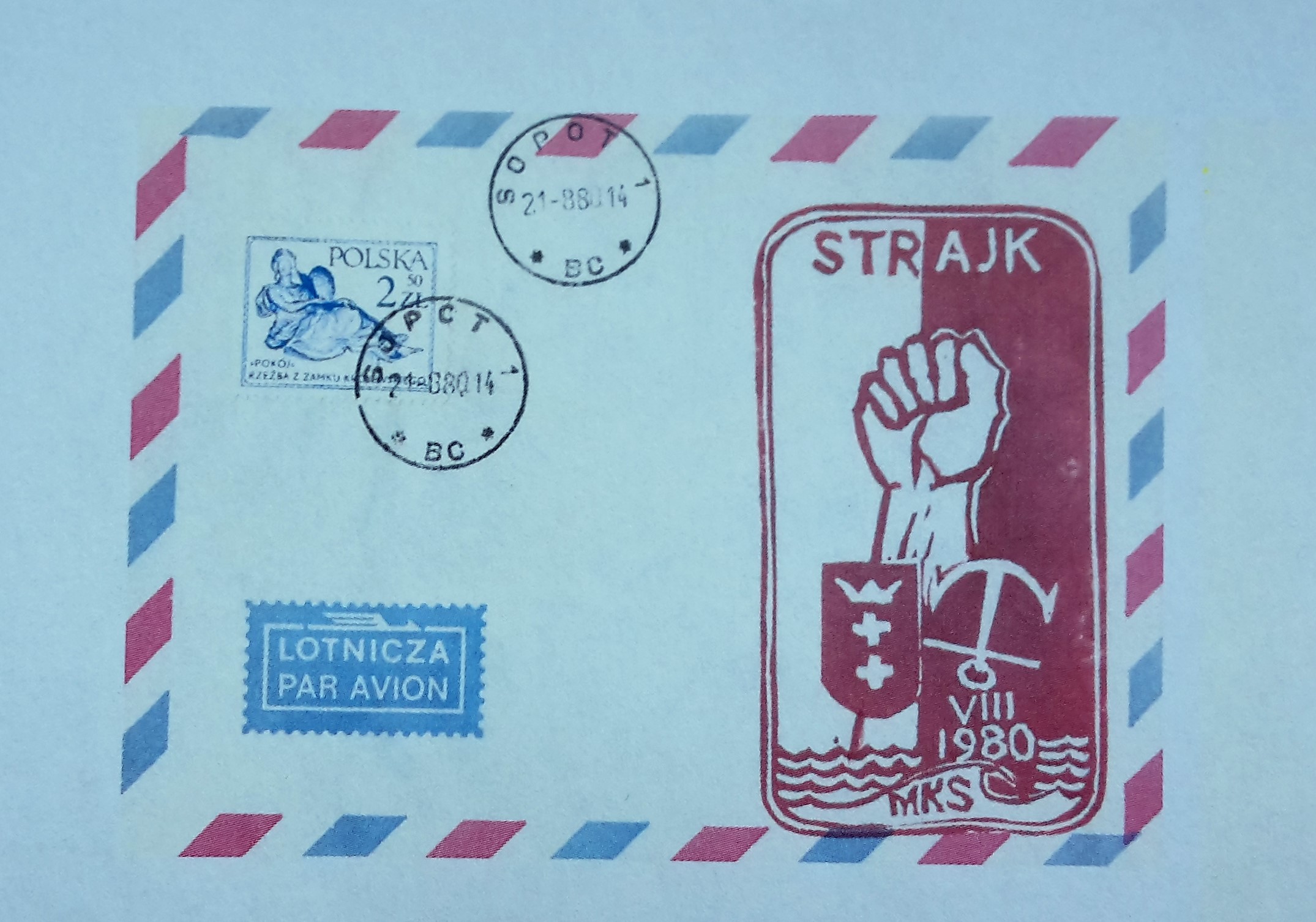

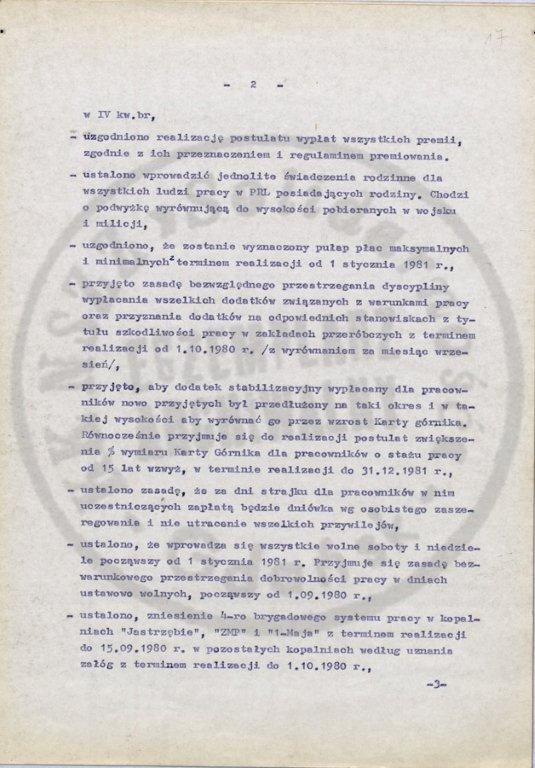

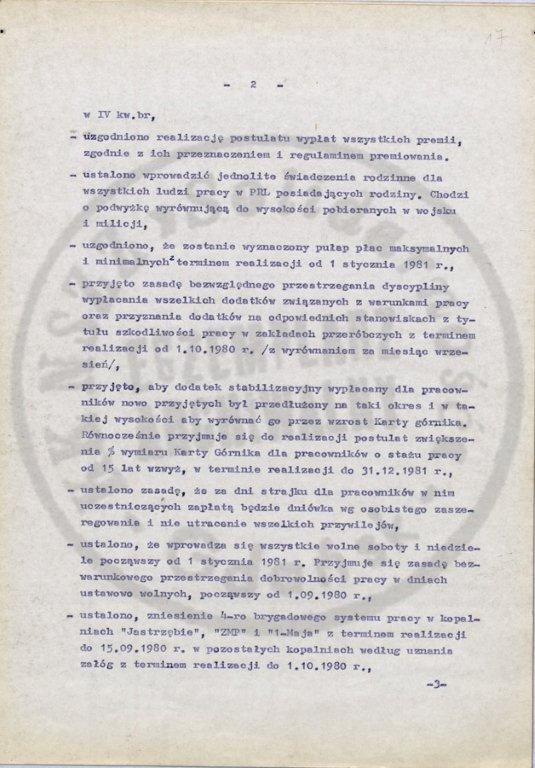

Kolekcja zebrana przez Michała Gucia stanowi obszerny zbiór znaczków, stempli i kopert dystrybuowanych w Polsce lat 80. w drugim obiegu. Znaczki stanowiły formę poparcia dla „Solidarności” i opozycji patriotycznej. Część z nich była tworzona przez artystów, a część przez samych działaczy-amatorów. Niezwykle ciekawą część zbioru stanowi poczta strajkowa oraz poczta obozowa. Michał Guć posiada jedną z większych kolekcji tego typu, którą zdołał zgromadzić dzięki osobistemu zaangażowaniu w walkę o przemiany demokratyczne.

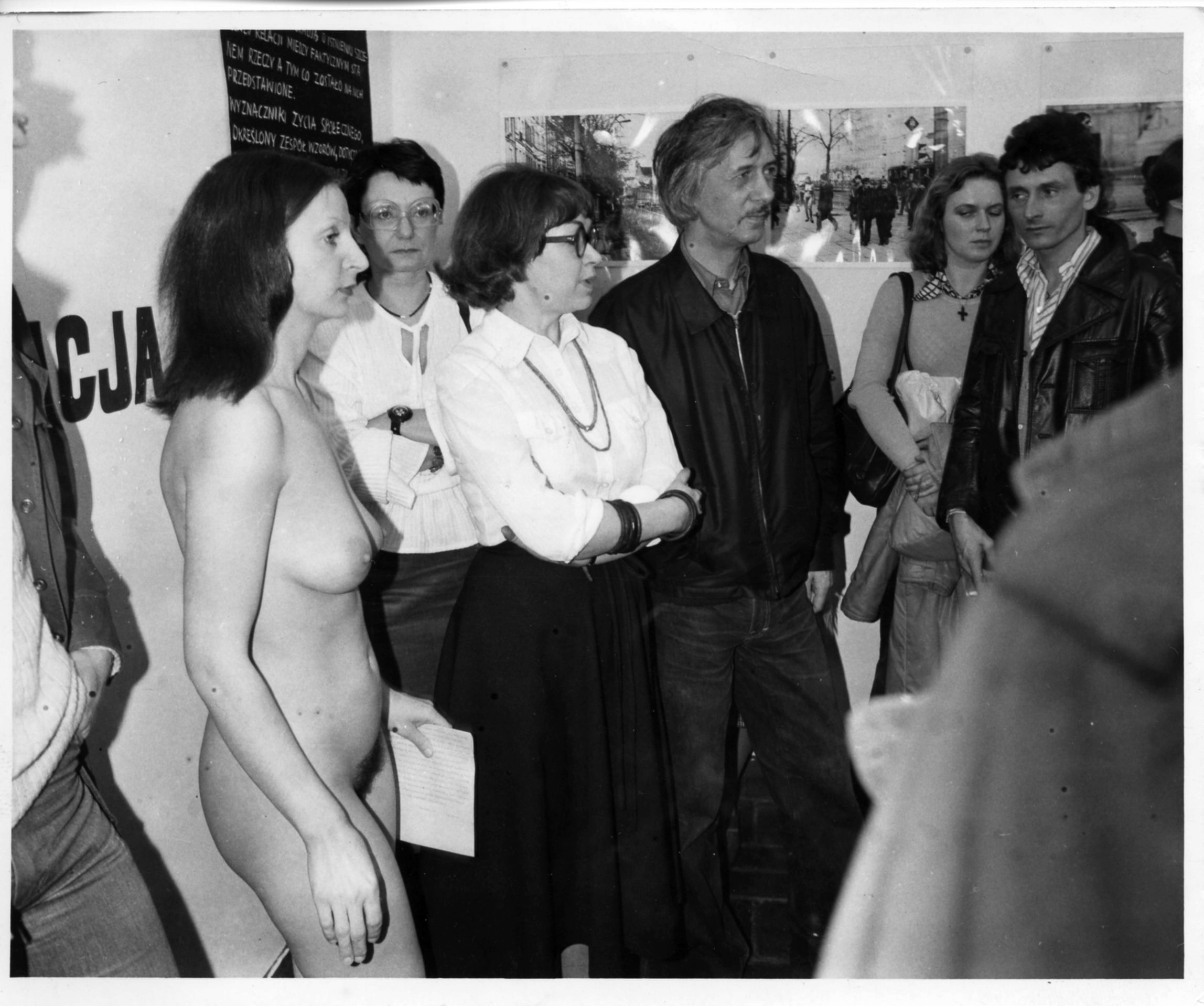

„Samoidentyfikacja” to performans oraz cykl fotomontaży, na których naga postać kobieca wkracza w publiczną przestrzeń stolicy – czeka w kolejce, kroczy w gęstym tłumie przechodniów, czy staje naprzeciw umundurowanej policjantki kierującej ruchem.

Akcja polegała na wyjściu z przestrzeni galerii nago na reprezentacyjną Starówkę. Tam, pod znanym warszawiakom Pałacem Ślubów, performerka wmieszała się w grupę świadków i gości weselnych wiwatujących po ceremonii. Jak interpretuje to Muzeum Sztuki Nowoczesnej, artystka „skonfrontowała się w ten sposób z instytucją małżeństwa, determinującą jeden z komponentów kobiecości rozumianej jako schemat osobowości wytworzony przez kulturę patriarchalną.”

Podczas wernisażu fotomontaży Ewa Partum nago przed publicznością odczytała feministyczny manifest, w którym piętnuje nierówność prestiżu kobiet i mężczyzn w świecie sztuki.

W katalogu wystawy, którego druk przez rok wstrzymywała cenzura, Partum pisze o „statusie społecznym i kulturowym” kobiet, „rozumianym jako pewnego rodzaju suma ról, model wytworzony przez tradycję (…) pewien zespół funkcjonujący w świadomości społecznej”. Ten „wzór osobowy kobiety” nazywa „wytworem kultury patriarchalne”, który „upośledza kobietę przy pozorach respektu dla niej”.

Na stronie muzeum dowiadujemy się też o ówczesnym odbiorze wystawy przez władze i publiczność: „Niektóre zdjęcia/kolaże nie mogły być pokazane z powodu cenzury, np. zdjęcie nagiej artystki przed budynkiem rządowym. Otwarcie wystawy było zagrożone posądzeniem o pornografię i nihilizm. Zwyczajni przechodnie reagowali oburzeniem: « nie jesteśmy w Afryce».”

The story of acquisition of Iuri Shukhevych’s handwritten diary by Smoloskyp is unknown. This piece of Ukrainian samizdat was among numerous illegal documents smuggled by Smoloskyp couriers from Ukraine. In his diary, Shukhevych gives an account of Stalinist labour camps and ruminates on the destiny of the Ukrainian liberation movement. Smoloskyp and personally Osyp Zinkevych, who was a member of OUN’s leading body, PUN) participated in the campaigns in defence of Iuri Shukhevych, son of OUN-UPA military leader, Shukhevych, who spent over thirty years in Soviet labour camps. This diary along with many other primary source documents (for instance, the full collection of the documents of the Ukrainian Helsinki group) was used by Smoloskyp in their numerous publications on Shukhevych and other repressed Ukrainian nationalists.

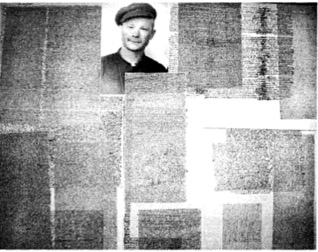

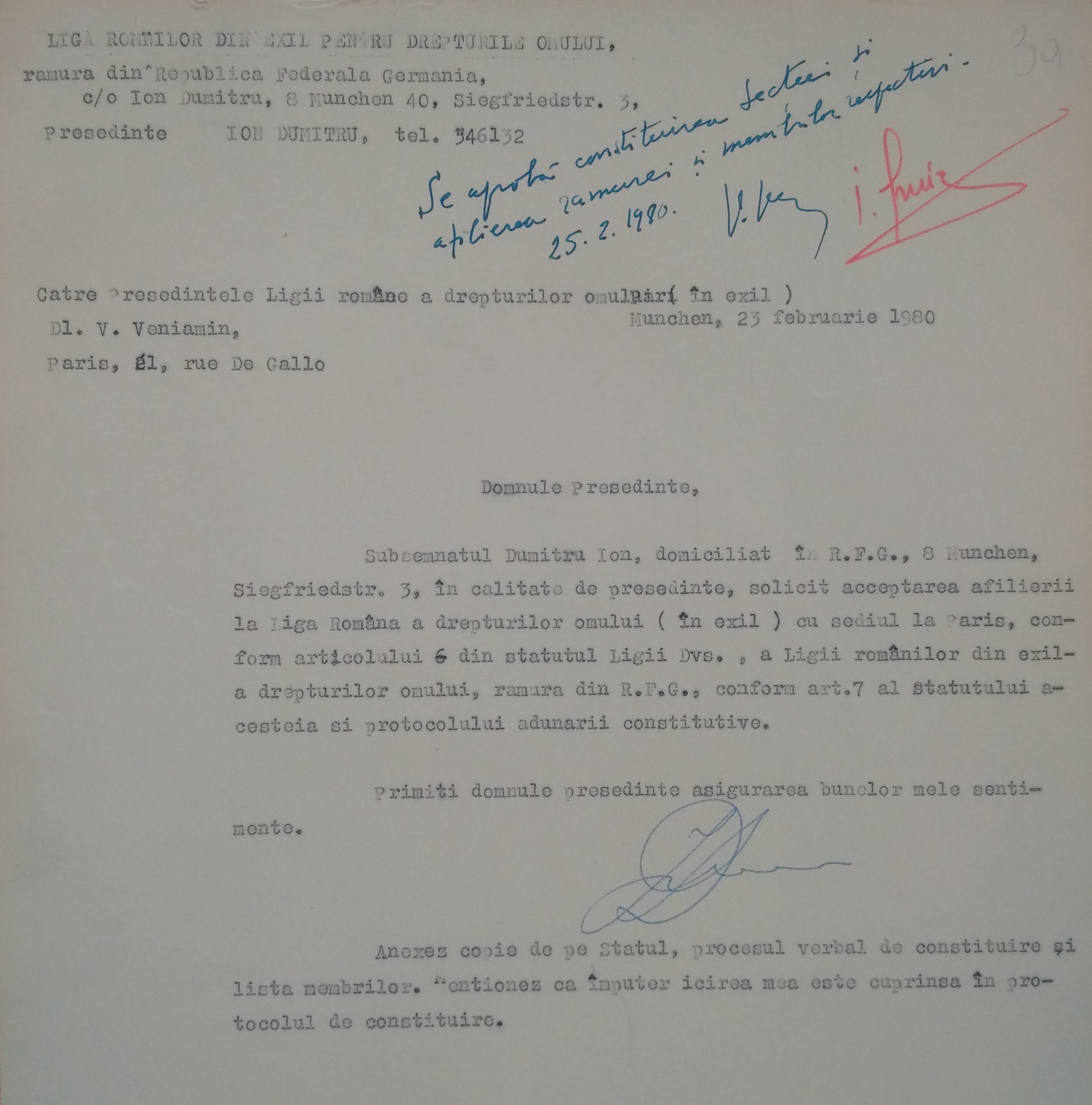

This document is an important source of documentation for the understanding and writing of the history of the Romanian exile community in the 1980s. It concerns the organisation that Romanians of the emigration established to unmask the wrongdoings of the communist regime in their native country to the West in the hope that they would find external support for the removal of communism in Romania. In particular, the document illustrates exile actions for the observance of human rights in Romania, as it testifies to the existence of a political body set up for this purpose, namely Liga Românilor din Exil pentru Drepturile Omului (The League of Romanians in Exile for Human Rights). It had its headquarters in Paris and was coordinated by Virgil Veniamin, who was a personality of the exile. A graduate of the Law Faculty of the University of Paris in 1930, he was a professor of international law and a lawyer, as well as being a distinguished member of a Romanian political party, the National Peasant Party. The establishment of the communist regime found him at home in Romania, which he left clandestinely in February 1948, settling in Paris. In exile, he was particularly noted for his activity as president of the Carol I Royal University Foundation and as a member of the Romanian National Committee, considered by its founders as the Romanian government in exile. In the 1970s he was involved in a major scandal in the Romanian exile community when he was accused of collaborating with the Securitate in Bucharest. Today, based on the documents contained in the file on him created by the former Romanian secret police, it can be ascertained that he was indeed an agent of influence of the communist regime within the exile community. The document kept in the Ion Dumitru Collection is a request sent by the collector to Virgil Veniamin on 23 February 1980, asking him to accept affiliation to the central section in Paris of Liga Românilor din Exil pentru Drepturile Omului (The League of Romanians in Exile for Human Rights) of a newly established West German section based in Munich, in which Ion Dumitru had been elected chairman. In response to this request, Ion Dumitru received a favorable reply from Virgil Veniamin. Both documents, in A4 format, can be found in the private archive of Ion Dumitru at IICCMER.

Between 7 December 1980 and 6 January 1981, an exhibition was organized which was based on the objects in the folk religious collection in Esztergom. It was placed in the Esztergom Basilica, more precisely around the Holy Cross altar.

After the call issued on 6 January 1980, many objects were donated to the collection, so the exhibition could draw on 6,000 objects given by 240 donors. Icons, carvings, primers, chaplets, statues, embroideries, and religious manuscripts were put on exhibit as testimony to vibrant spiritual life. The purpose of the exhibition was dual: the organizers wanted to demonstrate the importance of religious objects, which were extraordinary in the communist period, and they also wanted to answer a question of raised by the churchgoing public: “What shall we send?” Zsuzsanna Erdélyi and László Lékai emphasized that they were open to every object which had something in connection with the subjective, the local, the folk, and official religious life.

The exhibition was a well-organized event which drew masses of visitors and also included showings by actors, actresses, and opera singers (Katalin Gombos, Anikó Rohonyi, Imre Sinkovits, Gábor Németh, András Vitai) and an organist (István Baróti). After their performance, excerpts of holy legends were read, and the event came to a close with meditation.

The exhibition was successful because many other objects were offered. On the other hand, the organizers faced the problem of how to deal with the names of the givers, how they could present the religious objects, and how they could help collect the artifacts.

Thanks to the exhibition, the collection grew continuously, and by 1985, it had doubled in size.

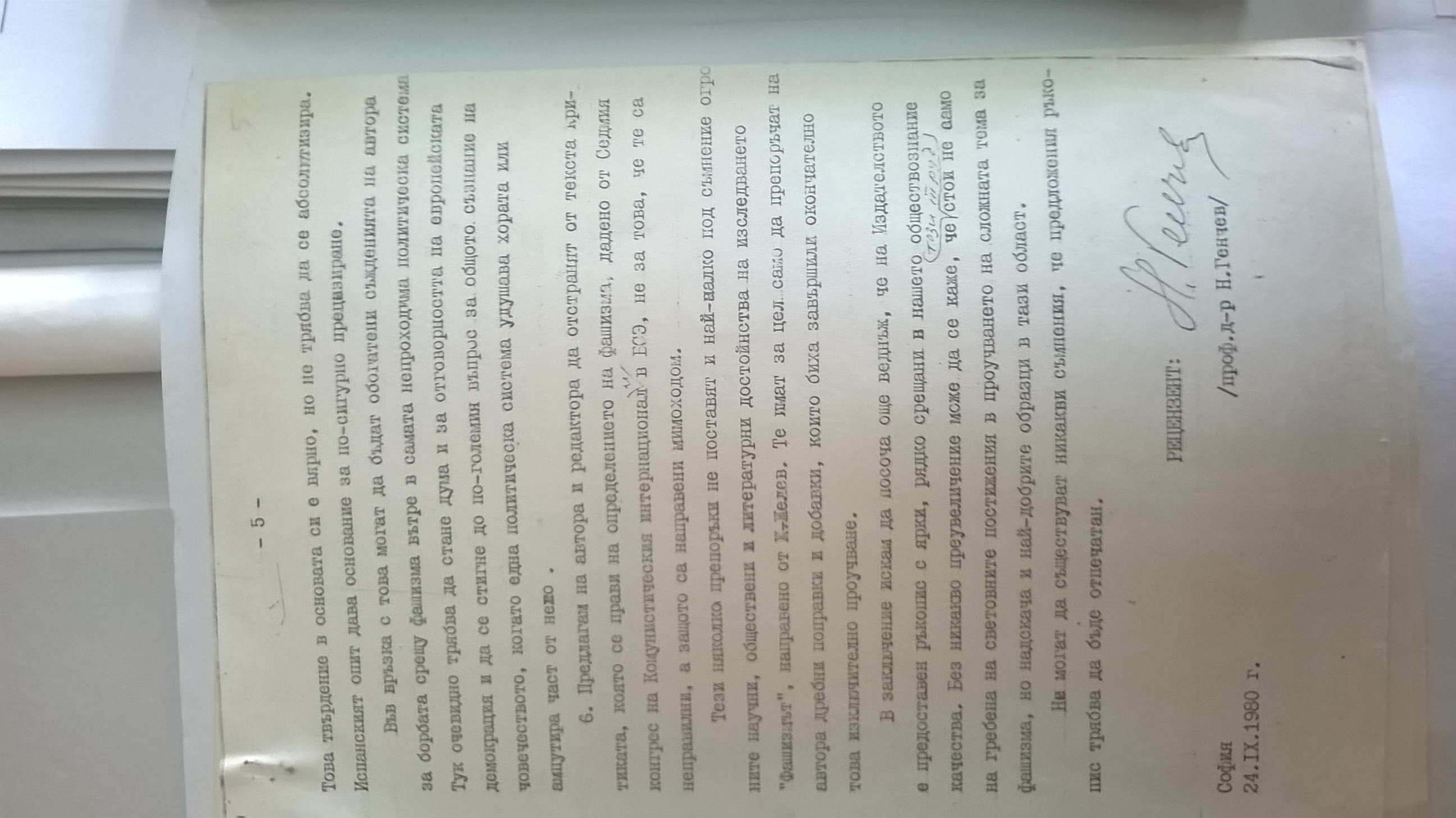

This featured item consists of an archival unit with describes the state party's ban of Zhelev's book Fascism and actions taken to prevent its distribution. It contains, among others things, book reviews by Prof. Nikolay Genchev and Prof. Mitryu Yankov and minutes of discussions about the book, from the period September 24, 1980, to March 25, 1983, totaling 186 pages. The book Fascism, originally entitled The Totalitarian State, was written by Zhelyu Zhelev during his period of internal exile in the village of Grozden, Burgas district (1966–72). In his work, Zhelev analyzed the totalitarian regimes of Nazi Germany, Fascist Italy, and Franco Spain, and described the basic principles of fascist regime. Even without directly criticizing communist governments, he presented obvious analogies between fascist and socialist states. This book represents not only Zhelev’s critical philosophy and sociology but also the difficulties of publishing non-conformist texts and the significance of samizdat work.After finishing the manuscript in 1967, Zhelev attempted to publish it in a number of state publishing houses, but was rejected on the grounds of “lack of paper” or “overfilled publishing plans”. However, the manuscript was quickly distributed as samizdat. In 1968, Zhelev started talks with the Freedom publishing house of the Czechoslovak Communist Party, but the suppression of the Prague Spring prevented the publication of the book in Czech.

In 1979 he submitted the manuscript to the People's Youth [Narodna mladezh] publishing house, the publisher of the Bulgarian Komsomol. He received two positive reviews by leading professors, the philosopher Kiril Vassilev and the historian Nikolay Genchev. In his review in September 1980, Genchev highlighted the qualities of the manuscript: "The author has shown the historical way of gaining power used by the fascist parties in Germany, Italy and Spain, the processes of subordination of the state to the fascist party, the transformation of the fascist party into a ‘state within a state’, the imposition of fascist ideology as a dominant one, not bearing any political or spiritual opposition. (…) The great social consequences of the empowerment of fascism have been shown: the unification of the spiritual life, the depersonalization of the individual, the imposition of an authoritarian way of thinking, the comical cult[A1] [A2] of the Führer, the transformation of the people into a crowd under the pressure of an unprecedented repressive apparatus and the overall moral degradation as a result of the historic experiment called fascism." He ends with the firm recommendation: "There can be no doubt that the proposed manuscript should be printed."

In March 1982 10,000 copies of the book were published in Bulgaria by Narodna Mladezh as part of the series “Library of Mavros. Popular Marxist Library”. The book caused a sensation. For three weeks, it could be found in bookstores before State Security prohibited its production and sale and confiscated copies because of its “lack of a partisan class approach”. Four thousand copies were destroyed.

The authorities responded with comprehensive and massive repression against all those involved in the issue. Three editors were dismissed: the editor of the book, poet Kiril Gonchev; the editor of the series, Violeta Paneva; the editor of political literature at the publishing house, Stefan Landzhev. The editor-in-chief of Narodna mladezh, Prof. Ivan Slavov, received a written reprimand as a disciplinary measure by the Bulgarian Communist Party (BCP). The reason was the “underestimation of the ideological and political shortcomings of the book Fascism.” Because of his extremely positive review, Genchev was forced to resign from his position as dean of the Faculty of History and his historical program on state Television were suspended for a period of almost four years. Asen Kartalov, who had written a positive review in the Plovdiv-based journal Fatherland Voice [Otechestven glas], received a "strong last warning before expulsion from the Party”. Zhelev himself, who had already been expelled from the Communist Party in 1965 and who at that time was a senior researcher of the Scientific Council at the Institute of Culture and head of the Culture and Personality Department, became victim of a sudden reorganization of the Institute. He was excluded from the Scientific Council and the Culture and Personality Department was closed.

The regime also ordered a critical review by the prominent scholar Mitryu Yankov, Head of the Contemporary Philosophical and Sociological Theories Department at the Bulgarian Academy of Sciences. The manuscript of the review, dated July 19, 1982 and 31 pages long, is preserved in the collection. Yankov’s criticism is scathing. He accuses the author of "too subjectivist a scheme and a subjectivist approach", of "deliberately ignoring the class approach, the author of this book tries to discredit the state and the political system of socialism through numerous analogies with fascism", "copying and compilation", and so on.

The review was written for the Philosophical Thought [Filosofska misal] academic journal. The editorial board of the journal held a discussion of more than 21 hours about Zhelev’s book on October 13, 1982. The full minutes of it are also part of this archival unit (i.e. the featured item). The meeting begins with a statement of its chairman Dobrin Spasov: "The book of Zhelev has become somewhat of a public phenomenon, which deserves the full attention of sociologists. It has become something like a bestseller and if the information is accurate, its price has reached 150 Leva in second-hand bookshops [average monthly salaries in 1982 were 197 Leva]" (42). In the course of the debate various opinions were expressed; several participants criticized Yankov's review and portrayed it as propaganda without serious scientific arguments. Finally, the chairman of the meeting Dobrin Spasov assured Mitryu Yankov "that despite the heated disputes that have arisen here, we admire his courage to come up with a firm opinion of this issue, on which many experienced comrades avoid giving their opinion." The review was eventually published under the title "For Scientific, Marxist-Leninist Analysis of Fascism" (Filosofska misal, no. 12, 1982). The main accusations against Zhelev’s book were the lack of a “partisan class analysis of fascism” and plagiarism of Karl Popper's "The Open Society and Its Enemies”.

The featured archival unit also contains the open-letter response by Zhelyu Zhelev. In his letter to the editorial board he demanded that the journal either produced proof of the accusations of plagiarism or to write a public apology. If not, he threated to sue them. The editorial board of Filosofska misal was overwhelmed by letters of protest from those prominent in academia and in cultural life who expressed their “indignation that scornful articles in the spirit of the 1950s are being given space, while not giving the oppressed the opportunity to respond” (as one letter writer wrote).

The documents of this feature item, thus, not only show how the state party tried (unsuccessfully) to silence critical voices; they also make clear that there was room for open disagreement, and that the oppression of prominent thinkers provoked protest.

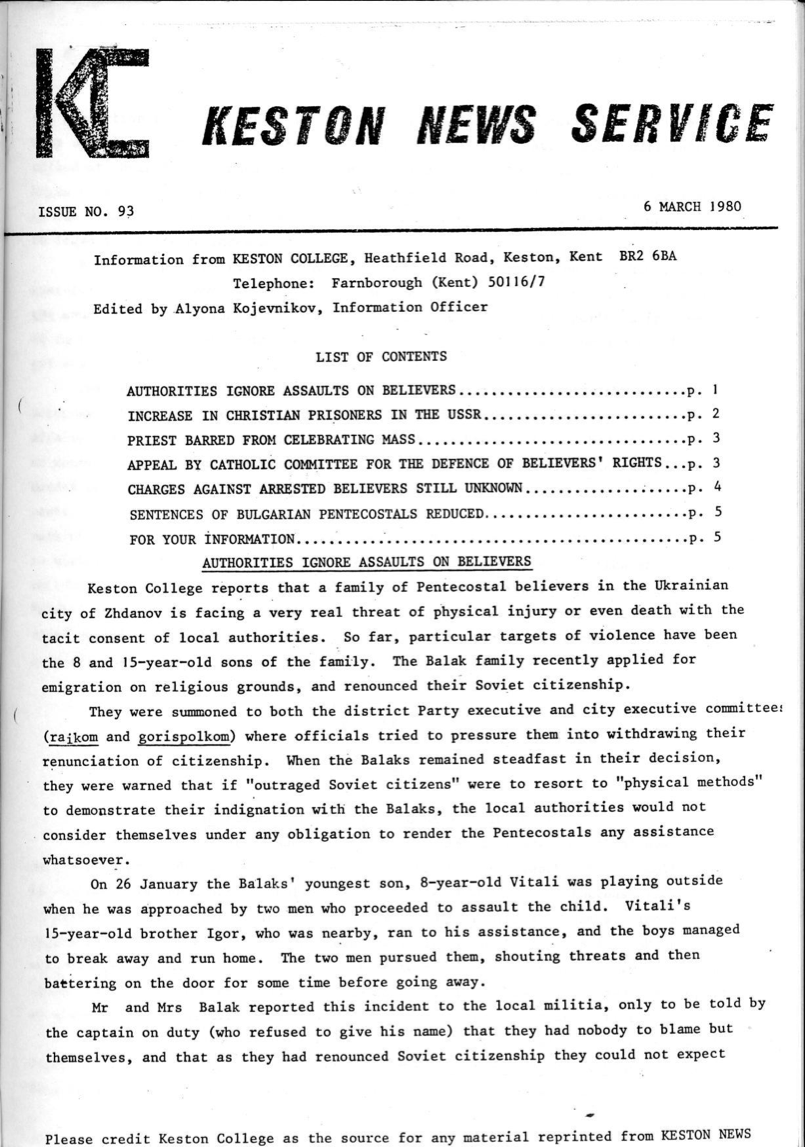

The ninety-third issue of the Keston News Service (KNS) is one example of the kind of information disseminated by the Keston Institute. This particular document details incidents of a Pentecostal Ukrainian family being accosted by local Soviet authorities for applying for emigration and renouncing their Soviet citizenship. The youngest son appeared to have been physically assaulted by two unnamed men, but the family was denied legal recourse on the grounds of their repudiation of the Soviet Union. Although Keston’s reporting on religious life in the Soviet Union was not always explicitly critical, the publication of reports on the conditions of religious life to a Western audience undoubtedly contributed to the public’s perception of the Soviet Union as anti-religious and lacking in human rights. The dissemination of such information via KNS coincided with various human rights campaigns initiated by non-state actors in the West and the Soviet Union, such as the Helsinki Groups. Keston Institute was part of a larger constellation of individual and organizational actors who transnationally supported political and religious dissent in the Soviet Union.

![Cover of the book: Vasilev, Vantseti 1991: Semenata na straha [The Seeds of Fear]. Sofia: Misal 90; 'Otvoreno Obshtestvo'.](/courage/file/n13322/Semenata_na_straha.jpg)

In 1988, Vantzeti Vassilev fled to Serbia, from where he moved on to Italy and, eventually, to New York in 1989. During his escape, Vassilev managed to bring out a copy of the manuscript Semenata na straha [The Seeds of Fear]. Another copy of the manuscript remained hidden at home, in the ceiling of his old barn, where he recovered it in 2016. In New York, Vantzeti Vassilev became an author of autobiographic novels. He also finished Semenata na straha [The Seeds of Fear] as a first-person account of the humiliation and impasse of a young scientist under the conditions of a totalitarian regime. The book was published in Sofia in 1991 with the financial support of Open Society Institute and then presented in New York.

Due to its success, the book was re-issued in 2011 and presented on various occasions, widely covered by the media.