The collection came into being on 23 February 1990, when the chairman of the Zadar municipal committee, Romano Meštrović, extracted the documents on the mass movement of 1971 in Zadar from the holdings of the Municipal Committee of the League of Communists of Croatia in Zadar as an ad hoc collection. The archival materials testify to the local communist purges after the quelling of the Croatian Spring. It mainly consists of the minutes of the inquiry panel, which investigated and indicted the reformist party members for nationalist, i.e., anti-socialist activities also in the cultural field.

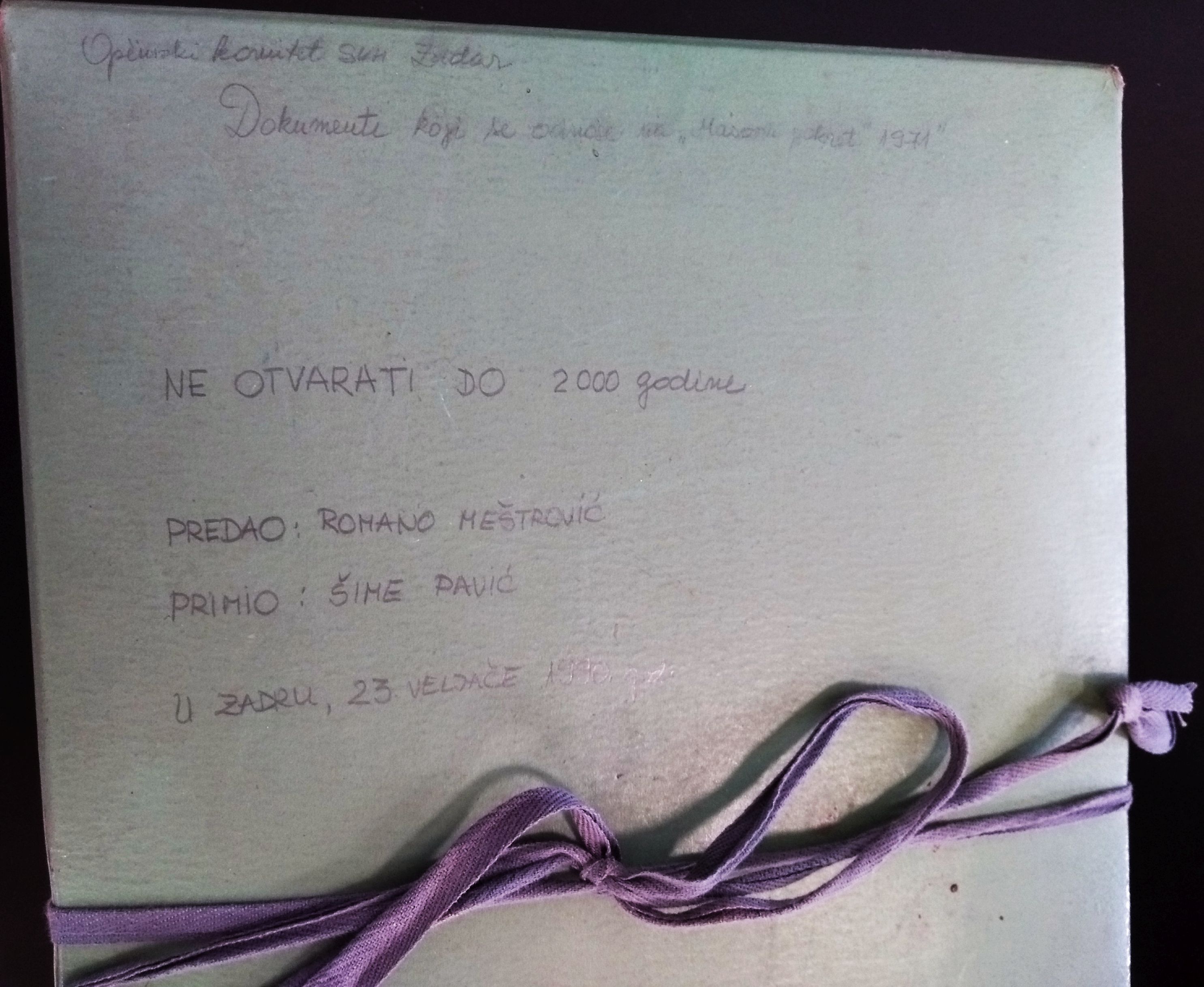

The material from the collection was placed in a single box labelled "Documents related to the ‘mass movement’ of 1971" with the note "Not to be opened until 2000," i.e., in 10 years. Besides these materials, Meštrović also took the documents related to the detention camp on the island of Goli, where Cominformists were interned after 1949. This box is labelled "Documents related to the Cominform resolution," and access was restricted until 1995.

The Croatian Spring was a liberal national movement in the Socialist Republic of Croatia, a consequence of the 1965 economic reform, which was aimed at introducing free market mechanisms into the self-managed Yugoslav economy. The economic reforms were followed by decentralisation processes along Party and state lines, which produced autonomy for the administrative and Party bodies in the individual republics and increased their control over their own economic resources. The economic reforms were followed by political reforms, culminating in the removal of the UDBA (the Yugoslav state security) chief, Aleksandar Ranković, in 1966 and the loosening of the secret police's grip over society. In Croatia, but also in the rest of Yugoslavia, social life prospered, freedom of media increased and ordinary citizens became more involved in their country’s political life. The post-1966 liberalisation also saw the rise of national sentiments and rivalries between the republics not only in the field of the economy, but also in culture (language and history) (Batović 2009, 5), because ever since the 1950s the regime had actively fostered the development of a common Yugoslav identity based on the socialist ideology of "brotherhood and unity.” This included the establishment of the Serbo-Croatian language, which was heavily contested by Croatian intellectuals.

During this period of liberalisation (1967-1971), the Croatian National Revival occurred, and Croatia came to the forefront of Yugoslav national controversies. In Hilde Katrine Haug's words, "the events in Croatia shook all of Yugoslavia to its foundations, leading to the greatest crisis the second Yugoslav state had seen" (Haug 2012, 233). The Croatian communists, led by the young and very popular Miko Tripalo and Savka Dapčević Kučar, brought the national question to the heart of debates aimed at the protection of Croatian economic interests in Yugoslavia. The communist leadership was soon accompanied by the Croatian cultural and literary organization Matica hrvatska and Croatian university students, who wholeheartedly supported the reform-oriented communist leadership.

All this national upheaval was later designated the "mass movement" (Cro. masovni pokret, abbreviated as MASPOK), which collapsed after the Karađorđevo meeting at the end of November 1971, where Josip Broz Tito convened the eleventh session of the Presidium of Communists of Yugoslavia, the Party's most authoritative body. The Yugoslav communist leadership interpreted the Croatian national movement as a restoration of ominous Croatian nationalism and labelled it as chauvinistic. The Croatian communist leadership had to resign from their positions, and approximately 2,000 people were criminally prosecuted in 1971 and 1973, and many more were expelled from the Communist Party in "purges." At the same meeting in Karađorđevo, Josip Broz Tito designated the city of Zadar as "the epicentre of the Croatian ‘mass movement’; as the epicentre of nationalism, chauvinism and counterrevolution, whose leadership headed by Mayor Kažimir Zanki [...], had to be chased away and thrown into the sea" (Diklić 2005, 344-45).

Although the inquiry of the Zadar reformist communist leadership had already been published as a source in 2012 (Diklić 2012), it was the Croatian novelist Ivan Aralica who drew special attention to the content of these files. In the book Smrad trulih lešina (The stench of rotten corpses, 2014), he described the case of his own "purge" from the League of Communists of Croatia in Zadar in the spring of 1972 when he was suspended from the Party due to accusations of not preventing the spread of nationalism and chauvinism in Zadar in the period 1970-1971. In the book, Aralica quotes the minutes of the inquiry panel, which questioned him and called this process "a differentiation" (Aralica 2014, 125). In Aralica’s words, “differentiation” was another name for the Russian “purge” (čistka). In his view, it was different from a purge to the same extent that Tito’s Stalinism was different from Stalin’s Stalinism, because for Aralica Tito never abandoned Stalinism as a method of government, of retaining the power. Rather, he applied it, that is, adapted to the circumstances in which he and Yugoslavia found themselves after Stalin had cast him out in 1948 (Aralica 2014, 138).

Aralica emphasizes that Tito’s Stalinism might not have been as violent as Stalin’s, but it was equally perfidious, and in order to make a difference, Tito called his purges " differentiation." Aralica warns that while Tito’s Stalinism, embodied in internment on the island of Goli or the prisons in Stara Gradiška and Lepoglava, was well described and well known, differentiations as purges in Tito’s innovation remained unexamined, and if they were mentioned anywhere, they were viewed in Tito’s favour: "this was not Stalinism, people were not sent to jail, they could emigrate abroad and there exchange a career as a lawyer for one as a waiter!" For Aralica, differentiation was a form of segregation and racism, and in his view the main goal of Tito’s differentiation was the recruitment of “politically/ideologically correct” cadres in all segments of society, and the marginalization of those who were “incorrect,” no matter how great their qualifications may have been. So, the main purpose of differentiation was to select those who were politically fit for future appointments, and to socially marginalize those who were incorrect, that is, unfit (Aralica 2014, 138).

The documents were treated as confidential in the communist period and served only for internal purposes. The collection is relevant to research the history of the Communist Party in Croatia and is completely opened to research.