The beginnings of Mirel Leventer’s private collection coincided with the beginnings of his life as a student. “When I entered the Faculty of Architecture – that is, in 1969 – it happened that the Architecture Club had just been founded. In my first year, I have to say, I didn’t have any connection with this club. In my second year, however, I began to go quite often. I found out that there was an Architecture cine-club and I became a member of this cine-club; and soon after, I took over coordinating it, because the person who had coordinated from the beginning had just finished university and, according to its constitution, the leader of this cine-club had to be a student. As I had come right after him, I quickly ended up running it. Out of it I made what nowadays would be called a ‘brand’ – with a logo, with all that was needed. That’s how Club A started” recalls Mirel Leventer. His collection grew from year to year, starting from 1970, the year of his first photo session in Club A. Until 1975, when he finished university, the collection was enriched with some dozens of items, mostly photographs, but also short and very short films. The collection also contains photographs from 1977, 1983, and 1984, when Mirel Leventer took several series of snapshots at various events organised by the club, this time not as a student but as a special guest of Club A.

The photographs and films were taken by Mirel Leventer using several cameras of his own, which he gradually acquired starting with the simplest model which could be found in shops in 1970, the well-known Soviet-made Smena 8 camera: “I bought them by stages. I never had charge of a camera. All the cameras are kept at home. I never threw anything away. I have them in my work room at home. I never had any reason to throw them away. First of all I had the simplest camera – it was a plastic one, Russian, Smena. After that, I had another Russian camera, Zenit Reflex. Then a German camera. Later, another four or five cameras. I keep them all in my work room.” Mirel Leventer also recalls how photographs were made before the digital age, when the roll of film had to be developed to obtain the negatives from which, by another development process, photographic prints on paper were obtained. All this quite difficult process could only be done in the dark, so as not to expose the film or the photographic paper. Passionate about photography, Mirel Leventer recounts how he developed the films in the faculty’s photographic laboratory and then at home, where he had set up a laboratory of his own: “All my photos were taken on [DDR-made] ORWO film. In the faculty there were some developing tanks. I also developed prints at home, because I had a photo laboratory at home too. The film was inserted in the dark, on a spiral – it was a standard frame, 35 mm, for photography. At the faculty there were some tanks that that three or four levels, so there were three or four of these spirals and I could process several films at the same time.” Regarding the short and very short films, Mirel Leventer also concentrates on the technical details of the materials that could be found for sale during communism in the network of photography shops and on the way in which filming, developing, and projection were done in that period: “The films were taken on my camera. I had a Russian camera, with a key, tiny, very comfortable. It ran with 2x8 mm spools, which could be found at the photo shops. For years they were in the shops; ORWO brand, from East Germany. ORWO film, not recording tape. It went on one side and on the other. Three minutes and three minutes: six minutes – that’s what fitted on a roll. And indeed that was more or less the format of our films at the cine-club. I would get a roll, film on it, and then develop it myself at the cine-club. At Architecture I had some little rooms – in five years I had four such little rooms, where I did the laboratory work. I developed these films in a developing tank, which resembled a magnetic mine. You introduced the film on a transparent spiral, poured in the solution on one side, there were two tubes. There were three solutions that were put in – the developer, a vinegar solution to neutralise the developer, and then the fixer. In the end you got a reversible reel – so it wasn’t a negative. Once it was dry, you rolled it onto a tape-recorder spool – they were also 8 mm. And you could do the projection.” It is interesting to note that the procedures for creating photographs on paper and reels of film involved costs pertaining to the basic materials that were quite high in relation to salary levels in the communist period. As Mirel Leventer explains, “a three-minute roll of film cost approximately 150 old lei. A film for the camera cost 25 lei. A beer was 2 lei. An average monthly salary: around 2,000 lei.” While cameras had to be bought from his own resources, for the ongoing expenses necessary for making photographs and films there was the possibility of funding through the University Centre, because the cine-club belonged to the Faculty of Architecture. “A sum was given through the school accounts office, I took cash, kept justificatory receipts, and bought what was needed,” recalls Mirel Leventer.

As for their themes, the films and photographs taken in this period covered several different types of event: music festivals, carnivals (one of the most famous carnivals at the time was actually that organised annually by the fifth-year students of the Faculty of Architecture), various ongoing activities of Club A, and the Freshers’ Ball (for new students of the Faculty). Sometimes films were made from amateur screenplays. “There were some enthusiasts who made little films. Club A was not subordinate, but was guided by the Students’ House [of Culture] of Bucharest. There was a larger cine-club there – they had funding from the students’ organization [UASCR – the Union of Associations of Communist Students of Romania]. We, at Architecture, received some funding from them too. However the main support came from our organisation. Together we held some events that propelled us to the foreground of student life back then. We needed reels of film, which were very expensive, and from time to time we received from the University Centre or the House of Culture, from Emilian Urse [who ran the cine-club at the Students House of Culture of Bucharest], a legendary figure for cine-clubs throughout the country, funding for projects, as we would say today. And the projects began to appear,” says Mirel Leventer.

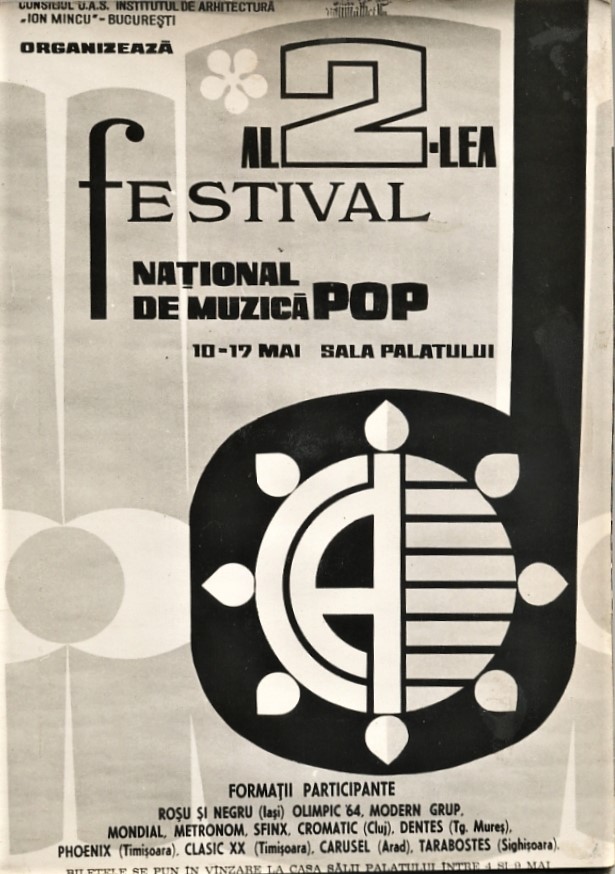

He illustrates this statement regarding the similarity with projects in the post-communist period by recalling an event that was to resonate in the Bucharest student world: the Second Club A Festival in 1971, organised this time entirely at the Palace Hall, following the success of the first festival, in 1969, which had taken place at the Students’ House of Culture, with only the gala being organised in the Palace Hall. “The greatest help came from Mac Popescu, who was himself a legendary university leader at the time. He was a professor, dean, rector and also a great supporter of young people and of student movements – whether artistic or sporting. As far as I was concerned, he was of enormous support. […] He actually stopped me and said, as he knew that we made films at the club, that he wanted us to film ‘big things that are going to happen.’ More precisely: the 1971 pop music Festival – a super-festival organized by the Architecture Faculty at the Palace Hall. It was right at the time of Ceauşescu’s famous July Theses. It was a festival that caused a bit of a stir and, in that turbulent year, we took some knocks. Some had to repeat a year of university. I was lucky; I wasn’t in their sights. We managed to film at that festival – I remember that we had very good funding and we used colour film. An 8 mm film – that was the classic format that we used.” Regarding the Festival of 1971, Mirel Leventer adds a series of important details: “The Festival lasted a week. That’s why we filmed so much. The Festival was in May. The Theses that reoriented policy in Romania in the cultural area were in July. And the scandal came immediately after that. By the way, the Festival opened on 10 May; that date didn’t help us at all in the eyes of the communists, because 10 May was the former National Day of Romania, the Day of the Monarchy. Back then, at the Festival, I remember that we stuck the posters very well – we were architects and we knew how to do it, so we made them self-adhesive. It was hard, almost impossible to unstick them. The result was that until around 1981 traces of those posters could still be seen around the Palace Hall.” Mac Popescu also recalls the second Club A Festival: “The climate that had been created at the club led me to the idea of holding an event that would extend outside. […] Apart from the record of interest in the country, not to mention Bucharest (with thousands of people left outside), and the quality of the music, we achieved an extraordinary record: the Hall was packed with 5,200 paying spectators, with only 3,500 seats. […] Of course the event did not pass unnoticed and we had big problems…” In fact the Festival was then banned for eight years, until 1979.

There is an interesting story in connection with how these visual documents of recent history were saved. Mirel Leventer provides the details as follows: “The films are now in my possession; nominally, they initially belonged to the Architecture club, but now I am the custodian of these photographic and film documents; they are mine; I saved them from destruction. Morally, they are mine; I am their owner; the law of marine salvage applies – when you find a wreck, it becomes yours. […] I saved these shreds of history; I took them under my wing and they are mine. When I finished university, the accounts office asked me to hand them over as inventoried items. But I said that I wouldn’t give them to anyone, because I knew what they meant, what memory and documentary value these films had. After two changes of owner, they might disappear. So I kept them myself, and I think I did well, because they were preserved safely. On a similar pattern – following two or three changes of owner and caretaker – things happened at Romanian Television that are rather sad: films of inestimable value disappeared, probably for ever.” It is also worth mentioning the way in which he managed to save the film archive from potential destruction because of the lack of interest of those who administered the archive of the cine-club. All the films that were made had to be handed in with an inventory number, given that they had been made on reels bought with money from the University Centre. The method used by Mirel Leventer was to hand over various pieces cut during editing as if they were the whole films, so that the number of reels bought would correspond in the inventory to the number of films handed in: “About the accounts office, the people to whom I had to hand them in for the inventory: what interested them in fact was the spool as such. For things to be in order, I gave them from each spool what hadn’t been used after editing. There were a lot of spools that were given up during the editing; I kept them, put them in a bag, and handed them in, as a matter of management. Everyone was pleased. They had sorted out the accounting part without any problem; I kept the films, and they are still in useable condition today. And indeed, two years after I left, the cine-club at Architecture closed. […] I congratulate myself for having had the sense to keep this archive, for having had the sense to give them the rejects from the spools that were kept in a bag,” adds Mirel Leventer. In 1985, he left Romania and emigrated to Israel. Before leaving he handed over the entire stock of images and films to the person he considered to be the most appropriate to protect them: Mac Popescu. On his return to Romania in 1993, he recovered the whole collection, which had been preserved in ideal conditions by his former teacher and long-term friend.

In the last two decades of Romanian communism, Club A, together with the academic structure to which it belonged (the Bucharest Institute of Architecture, today the Ion Mincu University of Architecture and Urbanism), offered protection and a feeling that Mirel Leventer describes thus: “We didn’t feel the pressure of communism – we were, on the one hand, very much protected by Mac Popescu, and on the other hand, by the teachers there – they were very decent people, who didn’t push towards an ideologised zone. Club A was a real oasis of freedom in those times.” And he offers two specific examples in support of this statement. The first is illustrative because it shows that watching films that did not circulate through official channels, even films produced in the Soviet Bloc but that had had problems with the censorship or had been too highly praised in the West, could alert the communist authorities. It is interesting, however, that in view of Romania’s anti-Soviet orientation starting from the 1960s, Mirel Leventer places the origin of the problem, which he experienced for himself, more in the Soviet provenance of the film than in its non-conformism: “One evening, there was a big scandal about the Russians. A colleague of mine got some documentary films. Strange as it may seem, in those days it was harder to come upon a Russian film than an American one. Because Nicolae Ceauşescu had that madness of his, of distancing from the USSR. We showed these documentaries, during film evenings, but also [Tarkovsky’s] Andrei Rublev. We were summoned and given a talking-to by the authorities. But it wasn’t something with very serious consequences. Somewhere at a higher or a very high level, what we were doing was tolerated.

The second episode shows that the activities of Club A were not only tolerated but also protected, because this club in fact channelled the explosive potential of the younger generation in a direction that did not cause trouble as long as it remained a mere island of freedom in a sea of constraint: “About protection: it was in the evening, in the night of the Resurrection [the morning of Easter Sunday]. The evening was organised at the club. The Militia came to the door but we didn’t open. We had received orders from the University Centre, because the whole thing would be sorted out at a higher level. We slept for two nights in the club, and in the end we got off without any sanction. It had been sorted out ‘somewhere higher up,’ just as we had been promised. That’s another example, about our protection. Club A was something tolerated. It was a ‘safety valve,’ just as, most likely, there were many others in the last fifteen years of communism in our country. When a pot is under pressure, if you fix the lid down completely it can blow up. Well, somebody didn’t fix the lid down, and they let us have a certain measure of freedom. We weren’t open opponents of the regime; we weren’t shouting against the communist regime; but we felt very free in our world there. It was, if I can put it like this, a form of passive resistance.”

As regards the public impact of the Mirel Leventer private collection, it is worth mentioning that some films have been projected in Club A and then, between 1999 and 2002, they were included in the programme Remix on Romanian Television, which is still repeating some of these programmes. Similarly, at Club A there have been a number of photographic exhibitions with selections from Mirel Leventer’s archive. Many of the photographs have also appeared as illustrative material in various books published by Doru Ionescu and Nelu Stratone.