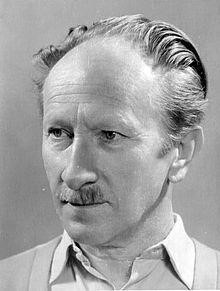

Edvard Kocbek was born in Sveti Juraj ob Ščavnici, near Maribor, in the province of Styria (Slovenia) on 27 September 1904. He was a Slovenian poet, essayist, writer and translator who, as a Christian Socialist, joined the Revolutionary Front and the Slovene Partisans under the leadership of the communists in the Second World War. He completed his secondary education in Maribor, after which he spent two years studying theology in the seminary. After leaving the seminary, he enrolled with a major in French language and literature at the University of Ljubljana. During his studies, he went to the Humboldt University in Berlin, where he attended lectures by German theologian and philosopher Romano Guardini. After completing the studies during the 1930s, he spent some time in France, where he met Emanuel Mounier and the circle around the French magazine L' Esprit. In 1936, he returned to Slovenia and began teaching French. Throughout his studies, he was a member of the Christian left, and in 1937, backing the Republican side in Spain, he expressed his opposition to the support of Slovene Catholics for General Franco in his writing. This move created a division in the Slovene Catholic movement, and his stance on the Spanish Civil War were condemned by Bishop Gregorij Rožman. Before the Second World War, as a Christian socialist, Kocbek principally condemned the communists, but in spite of that fact, he and his Christian Socialist group later joined the communists, particularly during the war, when they were unified within the framework of the Slovenian National Front.

After the war, he held several posts in the new communist regime in Slovenia and Yugoslavia, but he did not have any real power; thus, in the first Tito-Šubašić government, he was the minister for Slovenia. He came into conflict with the regime in 1951 when he published a collection of short stories entitled Strah in pogum (Fear and Courage), in which he critically dealt with the moral conduct of the Slovene and Yugoslav Partisans during the war. This is why he was placed in isolation and under the strict control of secret service (UDBA), and was forbidden from any public activity or writing. To survive, he translated French and German literature. He paid special attention to writing poetry at those times when he was banned from public life, which was highly regarded as the greatest achievement of Slovenian modernist poetry.

Though he was not imprisoned at that time, he was repeatedly interrogated by the secret police, while his home was wired with microphones. Several years before his death in 1975, Slovenian writers Boris Pahor and Alojz Rebula published Kocbek's interview in the Trieste review Zaliv (The Gulf) under the title “Edvard Kocbek – pričevalec našega časa” (Edvard Kocbek - a witness to our time). What the communist authorities found controversial in this interview was Kocbek's statement about the liquidation of 12,000 Slovene Home Guardsmen (domobranci) after the end of the war by the Partisans, which was the first public mention of these events after the end of the war. Kocbek also pointed out that from the very beginning of the war, communist terror against non-communist groups within the Slovenian National Front continued. There was a fierce campaign waged by the regime media against Kocbek, but ultimately he was not prosecuted thanks of international pressure, since Kocbek enjoyed a reputation as a great poet and writer.