István Bibó (1911–1979) was a Hungarian civil servant, politician, and political theorist. He came from a Calvinist intellectual background. His father was the director of the university library in Szeged, and he married the daughter of a Reformed Church bishop. In 1934, he received his doctorate from the Faculty of Political and Legal Studies at the University of Szeged. He then continued his studies in Vienna and Geneva. During his student years in Hungary, he wrote a number of studies on law and freedom; during his studies abroad in Vienna and Geneva, he attended lectures by the legal theorist Hans Kelsen and the philosopher and historian Guglielmo Ferrero.

In 1938, he became a notary at the Budapest Court of Justice. It was at this time that he came into contact with the Márciusi Front (“March Front”), a left-wing association of so-called népi (populist) writers and university students. He became a member of the Philosophical Society, giving his inaugural lecture on “Ethics and Criminal Law,” and in 1940, he began giving lectures at the University of Szeged. From 1942 to 1944 he wrote a lengthy essay “On European Balance and Peace.” It was later influential, but initially unpublished. In this essay, he analyzed post-World War I social development in Europe. In 1944, following the German occupation of Hungary, he drew up “Plans for a Peace Proposal,” which was intended to serve as a framework for postwar domestic arrangements and for the redress of social disharmony. In 1944 and 1945, he handed out exemption papers to hundreds of Jews and other persecuted individuals, and for this he was arrested and forcibly suspended from his post. When he was released, he had to go into hiding.

In 1945, Ferenc Erdei, the Minister of the Interior in the interim national government (himself a sociologist and a peasant-populist [népi] writer), appointed Bibó as head of the ministry’s administration department. In this role, Bibó helped draft the new electoral law, and he wrote a memoir criticizing the expulsion of members of the German-speaking minority from Hungary. In 1946, he was appointed professor of political science at the University of Szeged, and a year later he became an administrator for the Institute for Eastern European Studies. Meanwhile, he published a series of incisive essays on the problems faced in Hungarian and East Central European societies. His essays “A magyar demokrácia válsága” (“The Crisis of Hungarian Democracy”; 1945) and “Zsidókérdés Magyarországon 1944 után” ( “The Jewish Question in Hungary since 1944”; 1948) and his treatise A kelet-európai kisállamok nyomorúsága ( “The Misery of Small Eastern European States”; 1946) were recognized as cornerstones of modern Hungarian political thinking by the dissident intellectual movements of the 1980s. The communist regime, however, disapproved of Bibó’s ideas and activities, and in 1950, he was asked to retire. In 1951, he took up an independent position as librarian at the Eötvös Loránd University Library in Budapest.

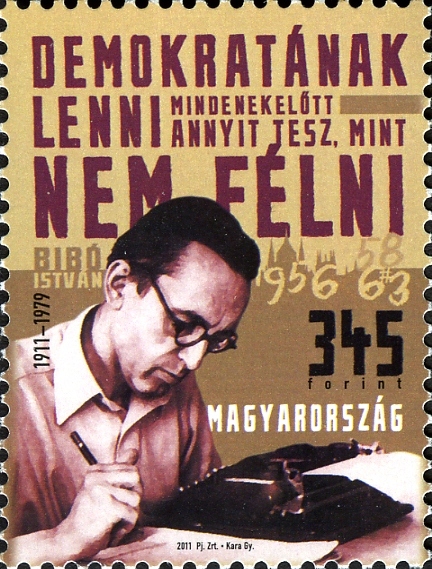

During the Hungarian Revolution of 1956, Bibó acted as the Minister of State for Imre Nagy’s second government. When the Soviets invaded on November 4 and then crushed the revolution, he was the last minister left at his post in the Hungarian parliament building. Rather than flee, he remained in the building for another two days and wrote his famous proclamation, “For Freedom and Truth,” as he awaited arrest. Later, he also prepared a proposal for “a compromise to solve the Hungarian question,” which he intended to pass to the Soviet leaders through the mediation services of the Indian embassy and President Nehru. When he was arrested in May 1957, he was tried and sentenced to life imprisonment, but he was released in 1963 according to an amnesty. However, hundreds of his fellow-prisoners, mostly young 1956-ers, students, and workers sentenced to life in prison were not released under the allegedly “general” amnesty under the pretext that they were simple criminals and not political prisoners. For many years, Bibó tried to help them regain their liberty by sending letters of complaint to the High Court of Hungary and Party-Secretary János Kádár himself, and even by trying to persuade, through clandestine channels, his Western contacts to launch public solidarity campaigns for the liberation of revolutionaries who were still being held in prison. He put himself at great personal risk by doing this, but not with much success: most of the people in question were released no earlier than the early 1970s.

After having spent six years in prison, Bibó took a job in the Library of the Central Office of Statistics, and he lived a quiet family life. He remained under the close watch of the communist secret police for the rest of his life, and he was not permitted to publish his works in Hungary. However, a few years before he died, he managed finally to publish a book in England “illegally,” i.e. without the approval of the Hungarian censors: The Paralysis of International Institutions and the Remedies. The book was published by Harvester Press, Hassocks in 1976. Bibó was not permitted to travel to the West, though the University of Geneva, of which Bibó as a student was a grantee, offered him a research fellowship; his request for a passport was repeatedly rejected according to the standard formula: “Your travel would offend the public interests of the Hungarian People’s Republic.”

In the last years of his life, Bibó took a certain satisfaction in seeing that his earlier political studies were becoming more and more popular among some young historians and dissident intellectuals in Hungary. His friends and followers intended to publish a book in celebration of his 70th birthday. Preparations were well underway when, in May 1979, Bibó died of a heart attack, six weeks after his wife died. His funeral in a Budapest cemetery turned out to be a silent show of anti-communist resistance attended by thousands of those who had known and respected him in the presence of hundreds of secret policemen and agents. In the name of Bibó’s friends, poet Gyula Illyés spoke at his grave, and János Kenedi spoke in the name of young dissidents. This was followed by the singing of the Hungarian national anthem by those present, except for the members of the secret police corps, who remained silent. One year later, the book, which in the meantime had evolved into a Bibó memorial anthology, was published without having been checked by the censors. It was a collection of writings by 76 authors in three thick volumes. It was the first impressive achievement of Hungarian samizdat.

The reception of Bibó’s works has undergone different trends over the course of the past forty years. When he died, a certain Bibó renaissance started with the republication, one by one, of his books, together with some unpublished works by different samizdat, tamizdat, and gossizdat publishers, often rivalling with one another. This intellectual fashion reached its peak by the fall of the regime; in 1989–1990, all political and intellectual circles, except the extreme left and the extreme right, tended to refer to his ideas and cite his statements as a kind of democratic and patriotic “credo,” at least up until the mid-1990s, when these ritual references fell out of the public discourse. By then, the Bibó “cult” seemed to have been replaced by “Bibó oblivion” and a “Bibó silence” again, as had been the case in the period between 1948 and 1956 and in the 1960s and 1970s. However, the 100th anniversary of his birth gave new energy to the commemorations, public debates, conferences, books, and films, proving that Bibó’s oeuvre was still relevant and still a part of public discourse and hampering efforts at ideological expropriation. The reason for the continued relevance of his perspectives and the interesting in his works seems quite simple: he was authentic, tolerant, and openminded. These moral and intellectual qualities were best described by one of his close friends, President Árpád Göncz: “His words and deeds were of the same material throughout his life.”

Since Bibó’s death in 1979, the family collection of his bequest, which includes personal documents, photos, manuscripts, books, and video and sound recordings, has been in the care of art historian and educator István Bibó Jr., who keeps the materials in his home in Budapest.