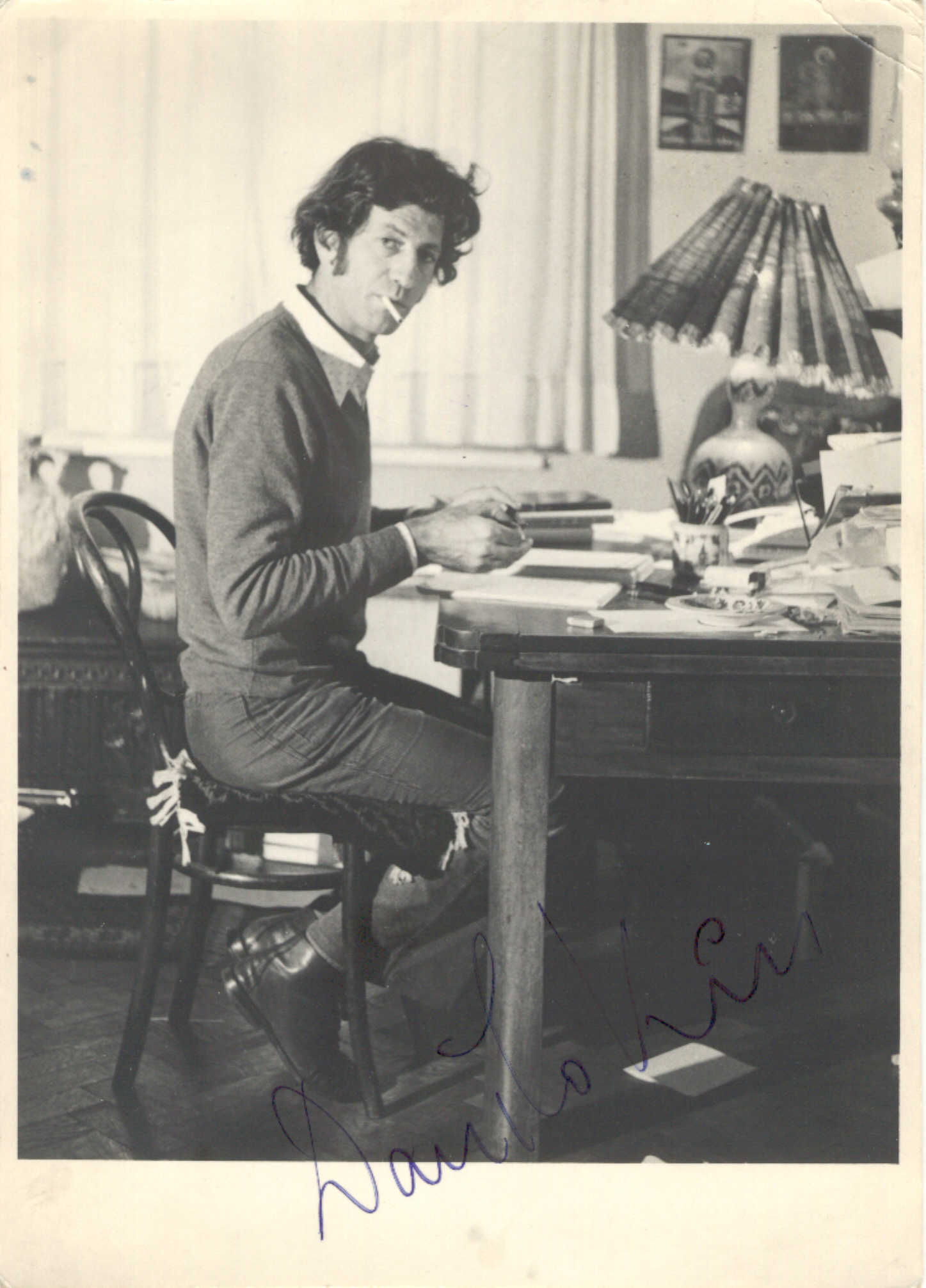

The Danilo Kiš Collection covers the author’s literary legacy. It is kept at the Archives of the Serbian Academy of Sciences and Arts (SANU). The collection includes a multitude of relevant materials from throughout the author’s life, starting from his childhood until his death. The largest part of the collection covers Danilo Kiš’s work and artistic projects.

Besides his written legacy, the collection also contains medals, awards and other formal recognition that Kiš received throughout his life. As per the author's will, they are located in the archives of SANU. Given that this is a personal collection, the holdings of the writer are organized as follows: I – Personal Documents, II – Working Documents, III - Awards and Achievements, IV – Family Documents, V - Photos, VI - Personal Items.

For those interested in understanding how the cultural opposition functioned, the most relevant part of this collection would be Personal Documents, particularly those records related Danilo Kiš’s trial (more in Featured Item).

A staunch anti-nationalist and anti-communist, Danilo Kiš was a non-conformist who “teased the pedantry of societies where labels matter more than the baggage." (Thompson, 2013, xiii). He described himself as a “European writer in the first place”, and “a Central European writer to the core” (Thompson, 2013, 20). Kiš elaborated on this: “Writers whom others call Central European or who describe themselves as such […] come to realise that their nonconformity stems from a certain reserve and an almost unconscious yearning for broader, more democratic European horizons.” (Thompson, 2013, 21).

Mirjana Miočinović has said in interviews with COURAGE that Danilo Kiš never wanted to be called a dissident, because he was not one. The theater expert and translator Miočinović was married to Danilo Kiš from 1961 to 1981. She maintained "[w]e lived in a system that did not force you to be part of it." Kiš reacted strictly to every form of censorship, but "he did not allow it to disrupt his attitude towards literature, he did not allow to be contaminated." Miočinović also explains that Kiš believed that "having nothing to do with people in power was a matter of mental hygiene". She says that he did not even want to socialize with people who were in ruling positions. Kiš's attitude towards power did not change over the years: "he has always been the same: far away from authorities." It was a matter of principle for him.

Already in the seventies, Kiš anticipated the danger of nationalist ideologies by maintaining: "Fear and envy are an engagement that demands no effort. Hell is comprised of the others (in a nationalist key, of course), and everything that is not mine (Serbian, Croatian, French) is foreign to me. Nationalism is the ideology of banality. Nationalism is thus a totalitarian ideology, while a nationalist […] is a coward who fails to admit his cowardice." (Debeljak 2016, Eurozine).

In 1978, Danilo Kiš published the book

Čas anatomije [The Anatomy Lesson] which was a response to criticism and attacks on his previous book

Grobnica za Borisa Davidoviča [A Tomb for Boris Davidovich, 1976]. The release of

Čas anatomije formed the grounds to prosecute Kiš. Although the court acquitted him of three counts of defamation, Kiš left Yugoslavia for France in 1979, embarrassed and disappointed.

Nevertheless, Miočinović considers Kiš not belonging to the category of diaspora writers, which some try to classify him as. "He always thought about returning and he wanted to return. His works were still published here and he has been rewarded here." The fact that Kiš was at the same time rewarded and persecuted illustrates the specifics of the Yugoslav system. "The center was in Belgrade, but there were several cultural centers opposing each other." If someone encountered pressures in one republic, the person could seek for more freedom for his work in another. In the publishing houses there have been people from the party, but nevertheless they were "from an undoubted literary reputation, they had the ear for the right thing and that was very important." Kiš's attitude toward awards is explained by his principled attitude, "take them, but do nothing to deserve them." Kiš thought it important to preserve one’s integrity and to do nothing to be in the favor of those who grant awards.

Miočinović claims: "Since the break with Stalin, there have not been norms that you had to hold on. No form [nor] content was imposed or prescribed for an artist to be articulated in his art." This all led to a major cultural change in the 1960s. "Those years were years of blossoming, it was a real boom. This created such a gifted generation of creative people."

The situation changed in the 1970s when the freedom of action characterizing the previous decades was significantly reduced. The first strike against Kiš occurred then, which Miočinović considers particularly perfidious because it was an attack on his creativity and his integrity as a writer: "If you go to prison, you can nevertheless consider yourself as a kind of hero. But when you have an attack attempting to destro] completely the one thing you were into, with every deprivation, attacking something you fully committed your life to - that is really the scariest".

The author's widow helped with the digitization of Kiš’s literary legacy after his death. The materials gathered are available on the Danilo Kiš: Ostavština [Danilo Kiš: Legacy] CD, which contains 4800 pages of written material, 300 minutes of video footage, and 400 minutes of audio. In addition, the CD contains a biography, bibliography, personal library, numerous photographs, personal and family documents, and Kiš’s entire literary estate. The CD can be accessed in the Archives of SANU in Belgrade.