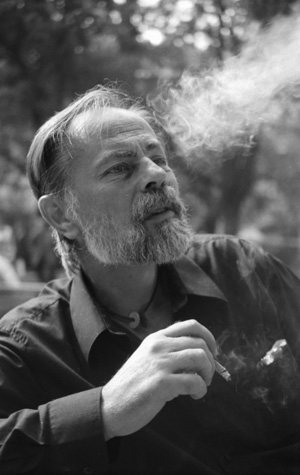

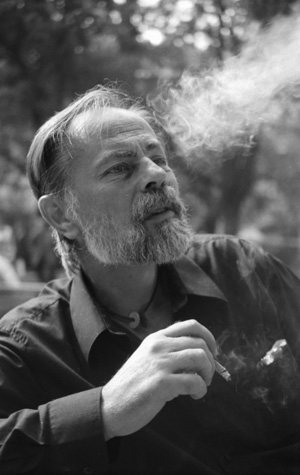

Zsolt Csalog (1935-1997) was an archaeologist, ethnographer, sociologist, illustrator and writer. Csalog grew up in a middle-class family in Szekszárd. His father was a well-known archaeologist. At 21 years of age, Csalog was involved in the Hungarian revolution of 1956. Later, he reflected on the events in his writings (e.g.

Budapest gyertyái or “Candles of Budapest,” 1994). In 1960, Csalog graduated from the Eötvös Loránd University (Budapest) as an archaeologist-ethnographer-historian. He married Éva Pócs (ethnographer) the same year. In the early 1960s, Csalog worked at archaeological excavations and published a number of scholarly articles on his research. He gradually turned to the ethnographic and sociological study of the culture of the Hungarian peasantry. Parallel to his professional career as an archaeologist and ethnographer, Csalog started to publish short stories. In the summer of 1965, the authorities launched an investigation against him. The investigation focused on a group of Hungarian dissidents with whom Csalog had been in contact during a trip to Belgium. Csalog was forced to give information about the group, and he gradually became an informant, a role he played until 1968, at which point he refused to continue to cooperate. In 1971, he took part in a research project on the social and educational conditions and employment rates among the Hungarian Roma, and also on Roma identity. The project was organized by sociologist István Kemény at the Institute for Sociology of the Hungarian Academy of Sciences. After a couple of months, for to political reasons, the project was cancelled. Though the project did not last long, it had an enormous impact. Until the early 1960s, sociology had been banned from the social sciences, in the Soviet Union and in Hungary. It was labelled a “bourgeois pseudoscience.” Beginning in the 1960s, sociology was allowed to exist as a discipline, but even in the 1980s it had an ambiguous status because it produced empirical results on housing problems, social conditions, etc. which contradicted the images crafted by the socialist regime.

This fieldwork gave Csalog inspiration for his professional career as a sociologist, and he also found sources for his writings. Beginning in the 1970s, using sociological methods, Csalog started to do interviews with people from different social (peasant, workers), ethnic (Roma), and political (apparatchnicks, participants in the 1956 Revolution) backgrounds. The interviews served both scholarly and literary purposes. Csalog used the transcriptions of the interviews to create new, coherent narratives that preserved the original voices and styles of the speakers. Csalog called this new genre “Dokuportré” (“Documentary portrait”), and he considered it a combination of sociography and fiction. Using this technique, Csalog published 10 portrait books. The first one appeared in 1971 (Tavaszra minden rendben lesz). It was followed by nine other books published in Csalog’s lifetime. The most significant of his novels was Parasztregény (see 2.19.5-6.). In the 1970s, Csalog worked as a part-time sociologist, ethnographer, and writer. In 1977, Csalog was one of many intellectuals to sign the Charta 77’ opposing the investigations against and trials of Czech intellectuals in Czechslovakia. Beginning in the 1970s, as a member of the Democratic Opposition Csalog regularly published writings in various samizdats (Profil, Napló, Beszélő). In the 1980s, he travelled back and forth between the USA and Hungary for several years. At the same time, he also participated in the emerging political opposition, and he continued to publish docu-portraits. Because of his writings (articles, portraits), he was still confronted by the authorities on several occasions (Egy téglát én is letettem or “I Also Laid One Brick”), 1989). In 1988, he was one of the founders of the Szabad Kezdeményezések Hálózata (Network of Free Initiatives).

Zsolt Csalog was related to and confronted by the regime on multiple levels. One can distinguish between direct political opposition (involvement in the Revolution of 1956 and acting as a member of the Democratic Opposition) and cultural opposition (publishing in samizdats and writing and publishing on sensitive social issues, such as poverty, discrimination, social deviance etc.). Empirical (sociological) research on these social issues was a relevant activity of the Democratic Opposition that enabled it to get a more nuanced grasp of the “realities” of Hungarian society. These “realities” were hidden or neglected by the Party for ideological reasons. In his documentary portraits, Csalog focused on the underprivileged and marginalized social groups of the Kádár regime, and he strove to amplify and disseminate their voices